paleontology

Meet your new flying nightmare: Thapunngaka shawi.

About 150 million years ago, a long-necked sauropod came down with a respiratory infection. The rest is history…or is it?

Yet another ocean monster has been discovered.

A school lesson leads to more precise measurements of the extinct megalodon shark, one of the largest fish ever.

Mastodons, rhinos, and even camels — all in the great state of California.

Scientists discover what our human ancestors were making inside the Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa 1.8 million years ago.

555-million-year-old oceanic creatures share genes with today’s humans, finds a new study.

Fossils of ancient creatures doing anything are rare. This one is absolutely unique.

Their ear structures were not that different from ours.

One million year old mammoth DNA more than doubles the previous record and suggests that even older genomes could be found.

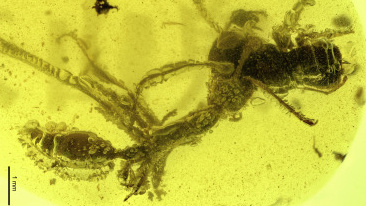

Scientists discover burrows of giant predator worms that lived on the seafloor 20 million years ago.

A new study tracks the human-dog relationship through DNA.

The microbes that eventually produced the planet’s oxygen had to breathe something, after all.

A new study bases its calculations on more than the great white shark.

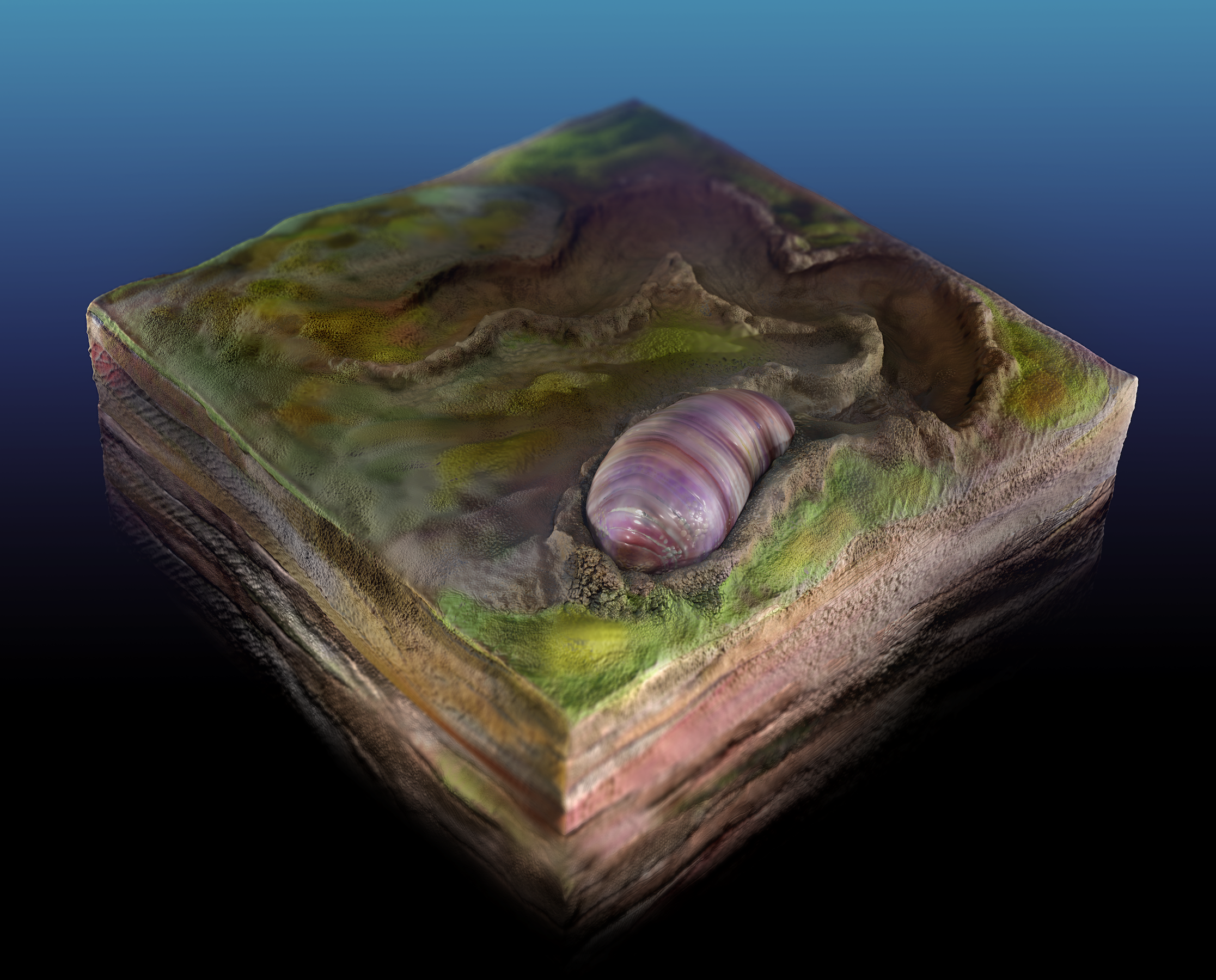

A rare titanosaur embryo was discovered with its skull preserved in 3 dimensions.

“You dream about these kinds of moments when you’re a kid,” said lead paleontologist David Schmidt.

Google’s Arts & Culture app just added a suite of prehistoric animals and NASA artifacts that are viewable for free with a smartphone.

Fossils depicting animals in action are very rare.

A recent analysis of a 76-million-year-old Centrosaurus apertus fibula confirmed that dinosaurs suffered from cancer, too.

Scientists uncovered the secrets of what drove some of the world’s last remaining woolly mammoths to extinction.

Batrachopus grandis, an ancient crocodylomorph, may have chased down land prey on its own two feet.

These Jurassic predators resorted to cannibalism when hit with hard times, according to a deliciously rare discovery.

Researchers think they know how a group of ancient sloths, who died thousands of years ago in Ecuador, met their untimely end.

Non-avian dinosaurs were thought terrestrially bound, but newly unearthed fossils suggest they conquered prehistoric waters, too.

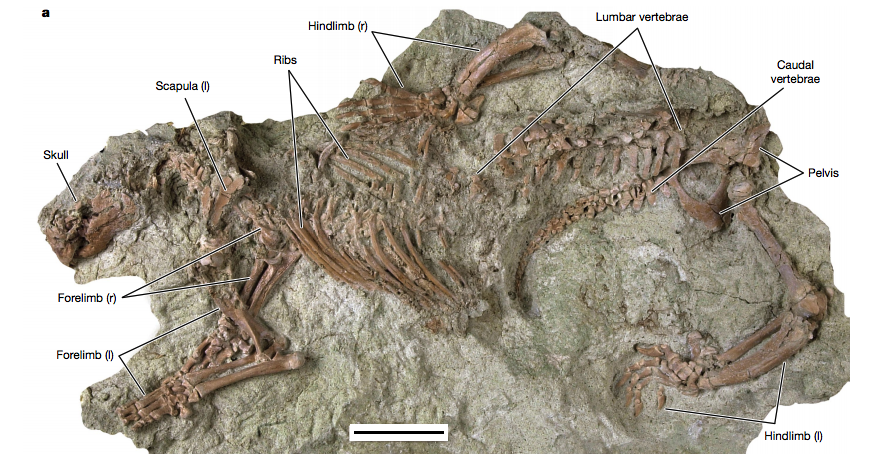

It’s likely the most complete skeleton that’s ever been discovered of the strange Gondwanatheria mammal group, which roamed the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana alongside dinosaurs.

The Sahara is a harsh environment today. It used to be much, much, worse.

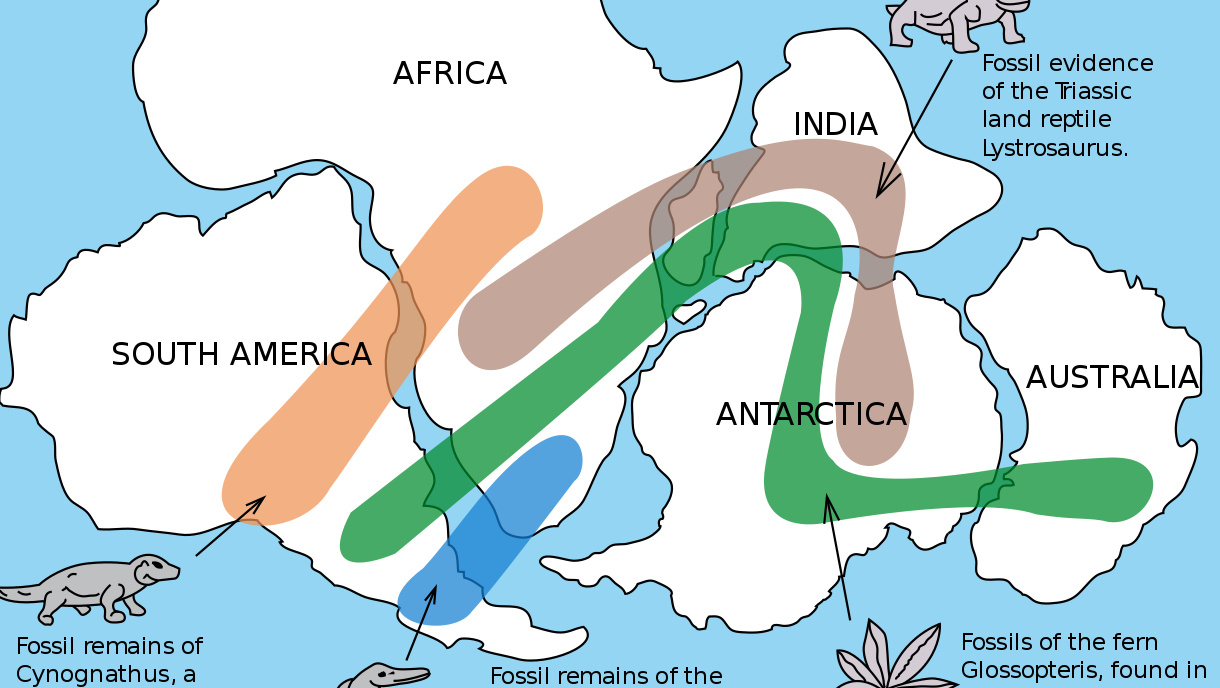

From the mid-19th century, fossils were used as evidence for continental drift – but mainstream scientists didn’t buy it until the 1950s.

Scientists discovered footprints made by some of the largest creatures ever to walk the Earth.

A new dinosaur species related to Tyrannosaurs found in Canada.