ancient world

This short story is a fictional account of two very real people — Anaximander and Anaximenes, two ancient Greeks who tried to make sense of the universe.

Scientists track down a puzzling early burst of oxygen on Earth.

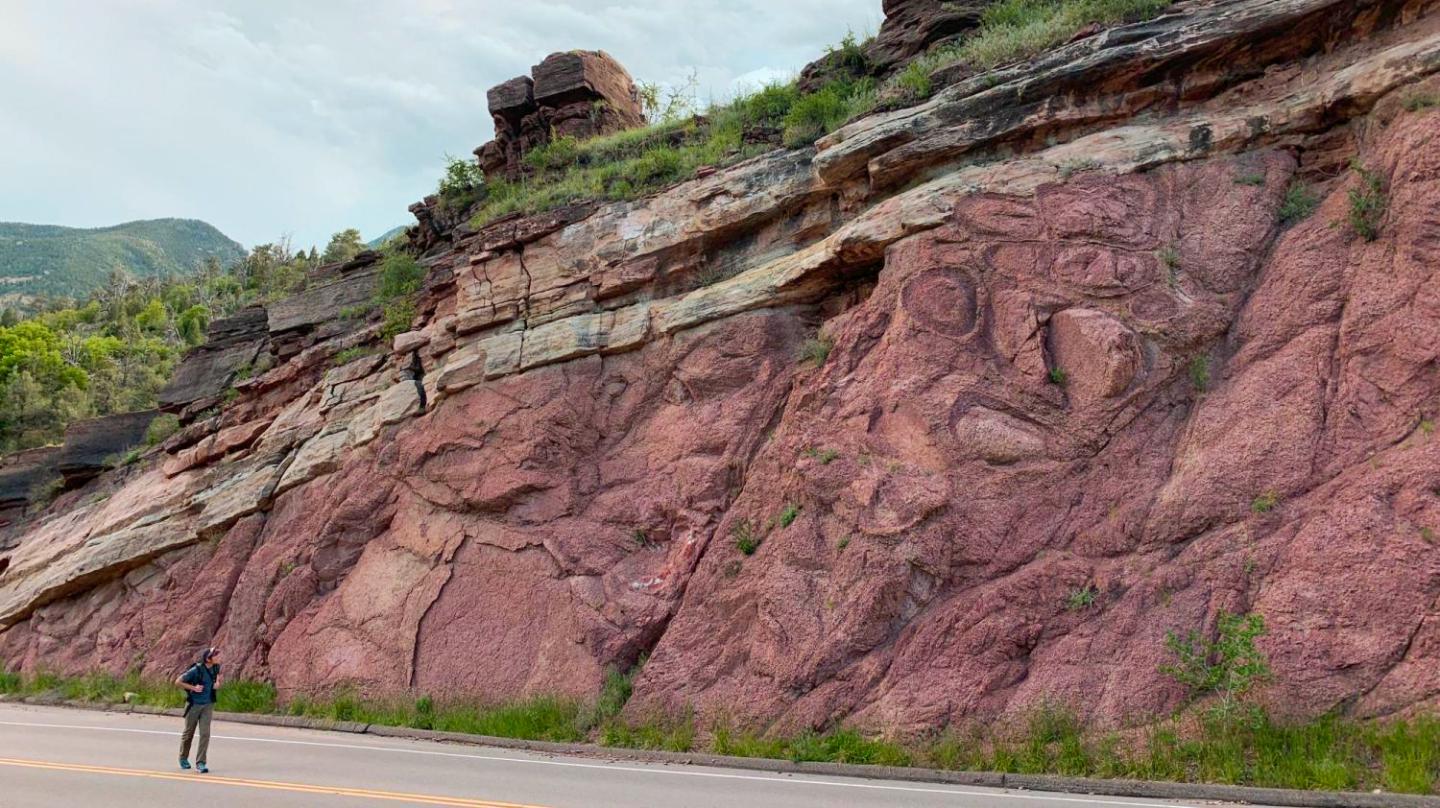

A puzzling — and huge — break in the geological record finally might be explained.

We should not romanticize ancient Egyptian culture.

Searching for happiness in the midst of personal or societal crises are nothing new.

Long before Alexandria became the center of Egyptian trade, there was Thônis-Heracleion. But then it sank.

Mastodons, rhinos, and even camels — all in the great state of California.

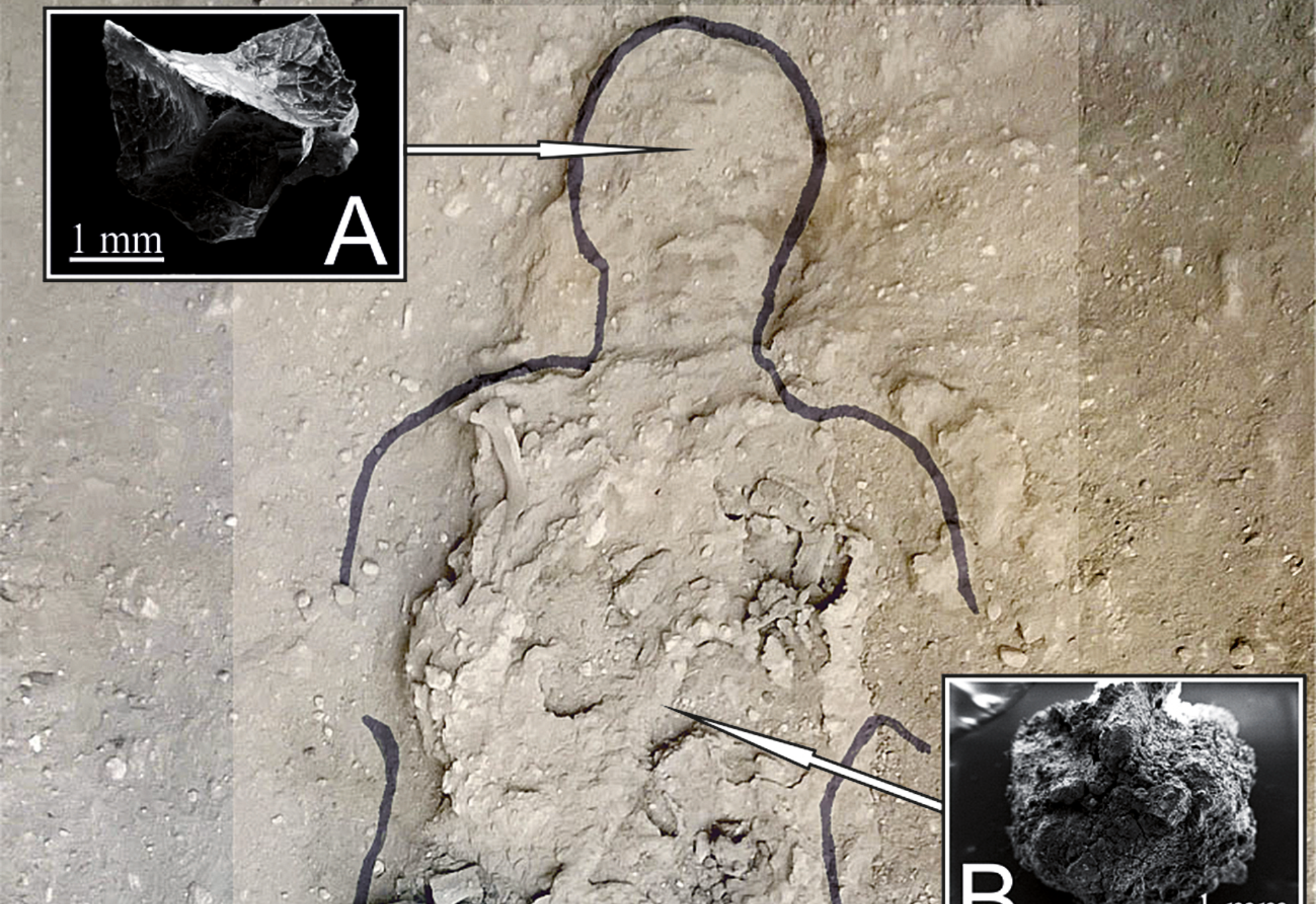

How do archaeologists know if someone was buried intentionally tens of thousands of years ago?

A study from Carnegie Mellon University tracks the travels of tarantulas since the Cretaceous period.

After years of speculation a team of researchers has pinpointed the age of this ancient mystery.

The chariot survived ancient eruptions and modern-day looters to become a part of the world heritage site.

Research shows that bone fragments of Jesus’s (possible) brother belong to someone else.

Waun Maun was an ancient Welsh stone circle that had an awful lot in common with Stonehenge.

Even tyrants and despots offer wisdom worth heeding.

While other factors exist, sexual prowess appears to have helped determine the role of Protoceratops frills.

Imagine Heraclitus spending an afternoon down by the river…

Traces of heroin and cocaine have been found in the tartar of 19th-century Dutch farmers.

New anthropological research suggests our ancestors enjoyed long slumbers.

A new study shows that at least one long-ago journey would have required deliberate navigation.

The rites we give to the dead help us understand what it takes to go on living.

The Chumash people poked bits of psychoactive plants into cave ceilings next to their paintings.

The heart of the religious ritual is mysticism, argues Brian Muraresku in “The Immortality Key.”

In “The Immortality Key,” Brian Muraresku speculates that the Eucharist could have once been more colorful.

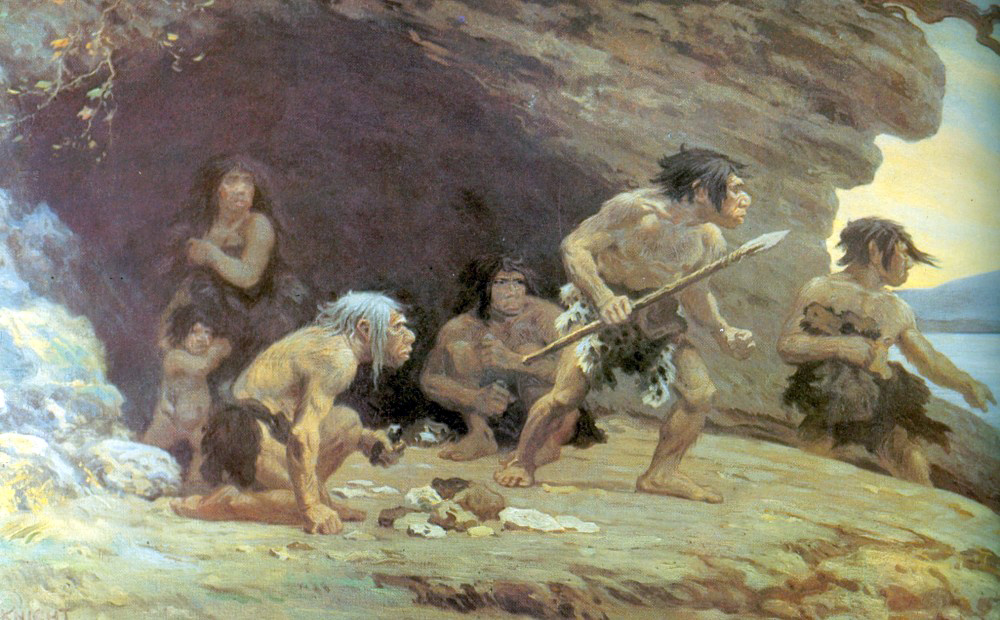

To war is human – and Neanderthals were very like us.

A new study tracks the human-dog relationship through DNA.

Rare structures and artifacts of the Viking religion practiced centuries prior to Christianity’s introduction have been uncovered by archaeologists in Norway, including a “god house.”

Researchers found a common element in the destruction of even the most powerful empires.

The young man died nearly 2,000 years ago in the volcanic eruption that buried Pompeii.

It’s hard to stop looking back and forth between these faces and the busts they came from.

Well preserved coffins hint towards more discoveries in a famed necropolis.