politics

Each year, over half a million migrants cross the deadly jungle separating Colombia from Panama in search of a better life in the United States.

Misinterpreted data may be distorting Western predictions about the future of China’s economy.

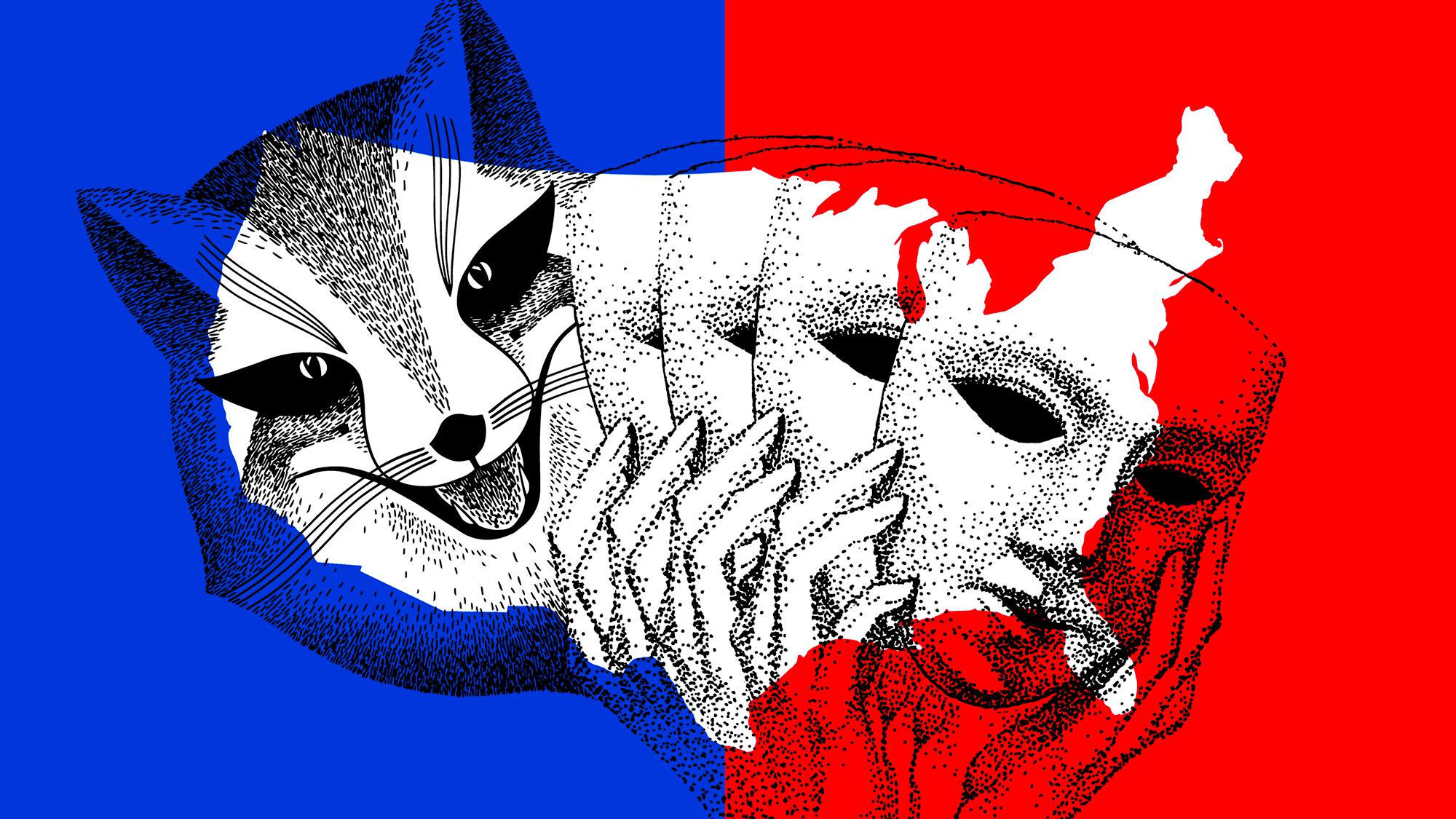

Autocrats like Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin fear democracy, yet go to great lengths to present themselves as democratic leaders.

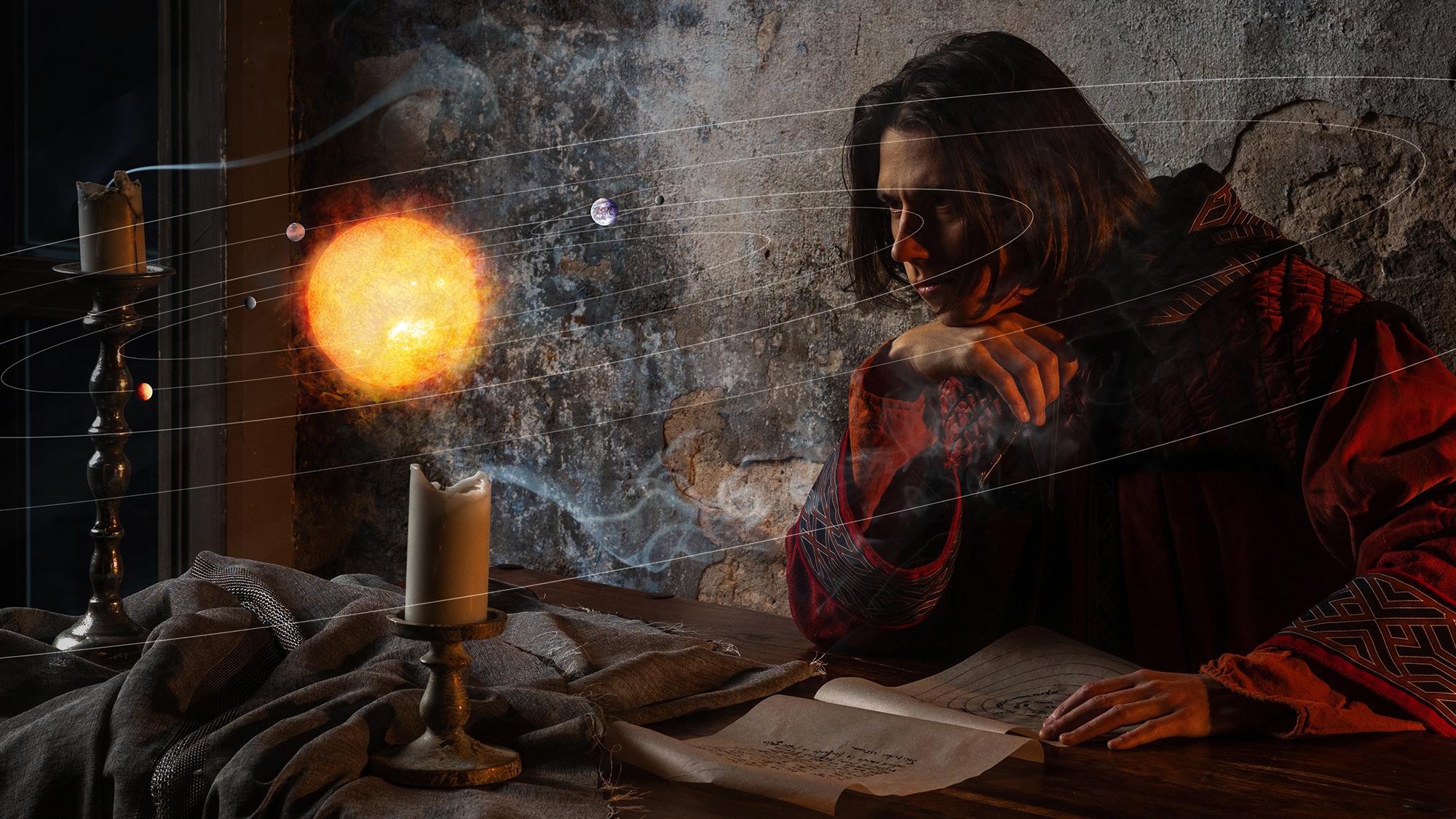

Before Constantine received his history-defining vision, a pagan Sun god paved the way for Jesus Christ’s triumphal entry into the Eternal City.

“This is much deeper than just ‘let’s figure out how we can get both sides to get along.’”

▸

15 min

—

with

Thinking as a group and going along with the loudest voices can feel easy and even natural. But to make real positive change in our world, it’s important to hear all voices and question the perceived majority.

▸

5 min

—

with

Social media isn’t the majority – it’s the vocal fringe.

▸

with

Scientology, QAnon, and Heaven’s Gate: why do we seek healing from cults?

▸

with

Some of these trends may be due, in part, to the lockdown.

Unstable politics and virtue signaling are responsible for creating bureaucratic nightmares.

Political partisanship might be a treatable condition.

These Roman Emperors were infamous for their debauchery and cruelty.

The US prison system continues to fail, so why does it still exist?

▸

18 min

—

with

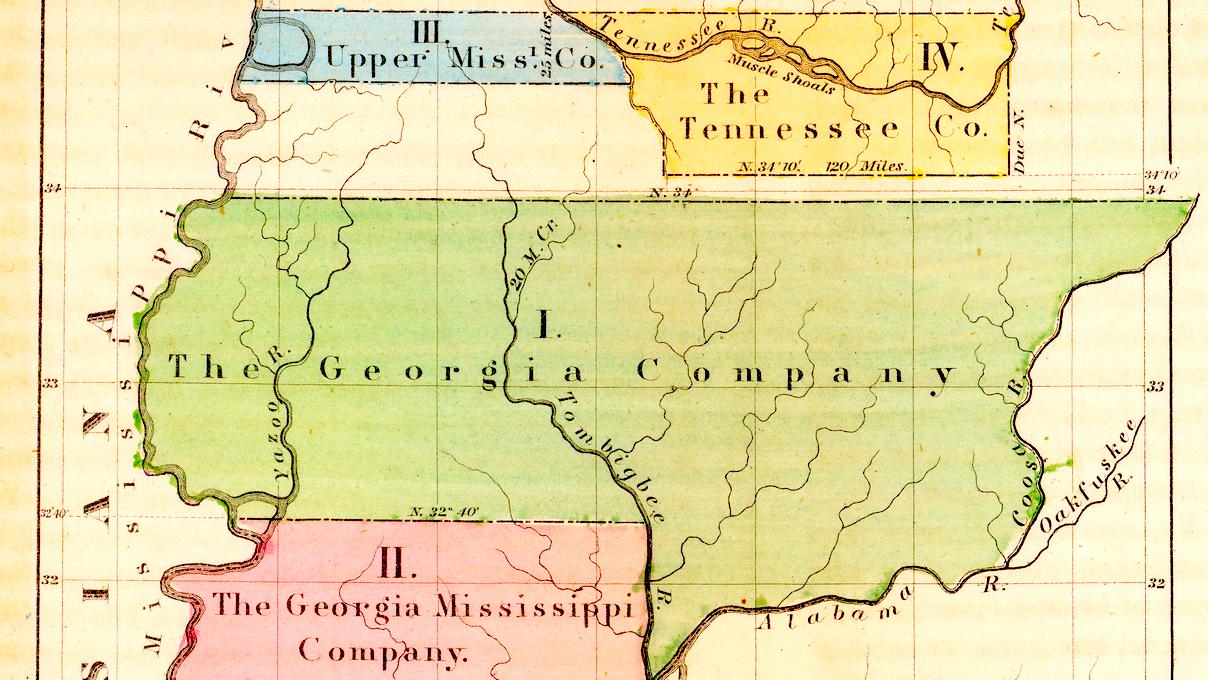

Without the now-obscure land investment affair, Georgia might have been a “super state.”

New research sheds light on the indoctrination process of radical extremist groups.

People often divide the world into “us” and “them” then forget about everybody else.

The public sphere should be open to conflict.

For some philosophers, hope is a second-rate way of relating to reality.

How the German political philosopher called out Henry David Thoreau on civil disobedience.

The independent news collective is teaching a new generation of journalists and citizens to spot the stories in plain sight.

For democracy to prosper in the long term, we need more people to reach higher levels of education.

How different people react to threats of violence.

Surprising as it may seem, we are all very good at denial. Negation, however, is a different phenomena.

The debate over whether or not there is a place for political correctness in modern society is not always black and white.

▸

13 min

—

with

The opening lines of Smartmatic’s $2.7 billion lawsuit against Fox News lay bare the culture of denial in the US.

Even tyrants and despots offer wisdom worth heeding.

7 scholars and legal experts dissect what you can and can’t say in America.

▸

22 min

—

with

“Deepfakes” and “cheap fakes” are becoming strikingly convincing — even ones generated on freely available apps.

Science doesn’t exist in a cultural and existential vacuum and its teaching shouldn’t either.

Welcome to the 13.8 relaunch, a new Big Think column led by physicists and friends Adam Frank and Marcelo Gleiser.