cognitive science

If love is an addiction, your first love is the first dose.

Reality is more distorted than we think.

▸

with

Eight-eyed arachnids can tell when an object’s movement is not quite right.

The same parts of the brain that help us navigate complex social interactions can also drive us to make wildly bad investments.

People often divide the world into “us” and “them” then forget about everybody else.

The present-moment awareness that stems from mindfulness practices may be the cost-effective tool that our society needs.

Being skeptical isn’t just about being contrarian. It’s about asking the right questions of ourselves and others to gain understanding.

▸

15 min

—

with

The famous cognition test was reworked for cuttlefish. They did better than expected.

Fractal patterns are noticed by people of all ages, even small children, and have significant calming effects.

Is the quest to upload human consciousness and ditch our meat puppets the future—or is it fool’s gold?

▸

14 min

—

with

These tiny fish are helping scientists understand how the human brain processes sound.

The compound found in “magic mushrooms” has significant and fast-acting impact on the brains of rats.

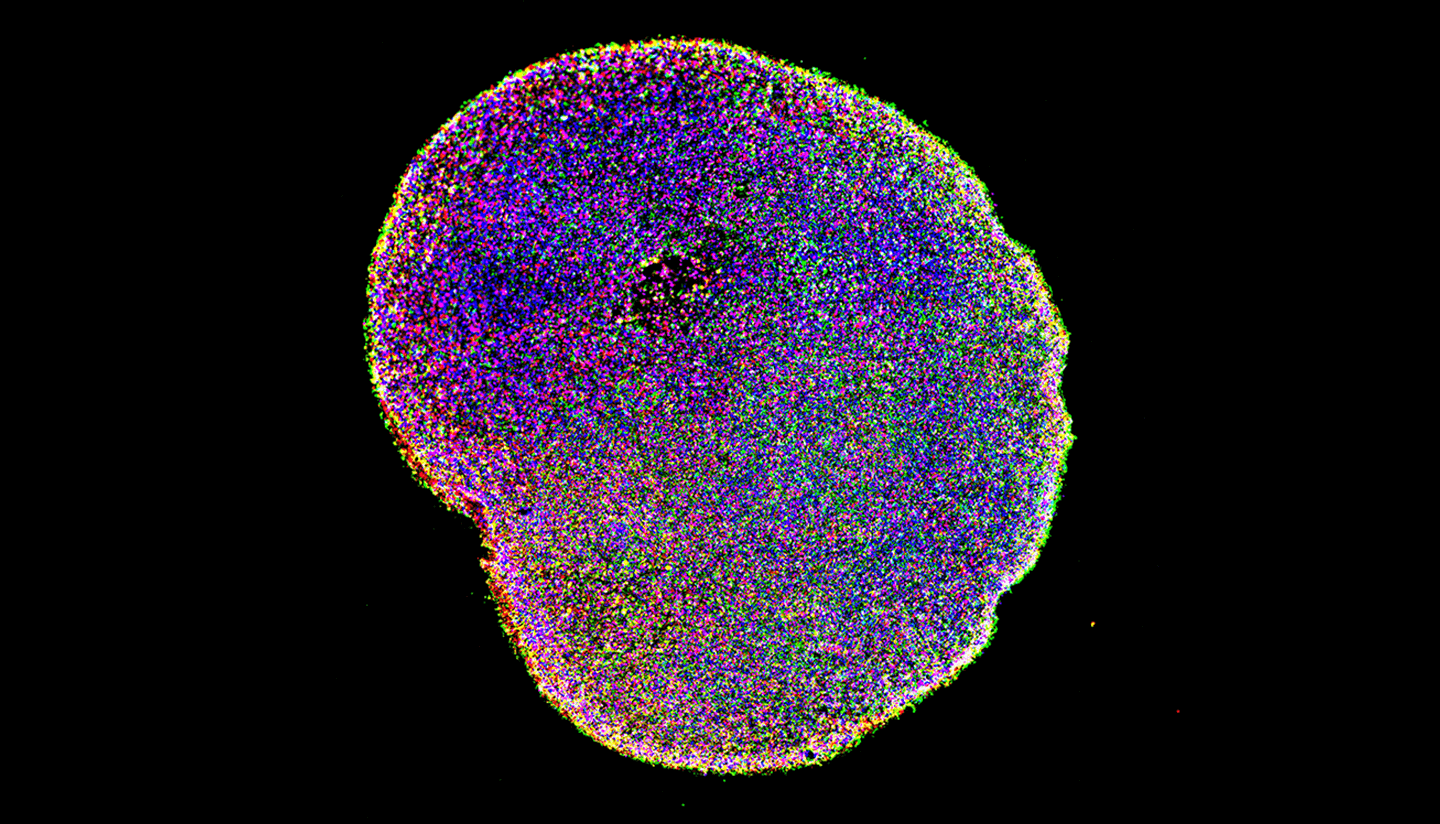

“Such studies will lead to a better understanding of brain development in both autistic and typical individuals.”

Certain colors are globally linked to certain feelings, the study reveals.

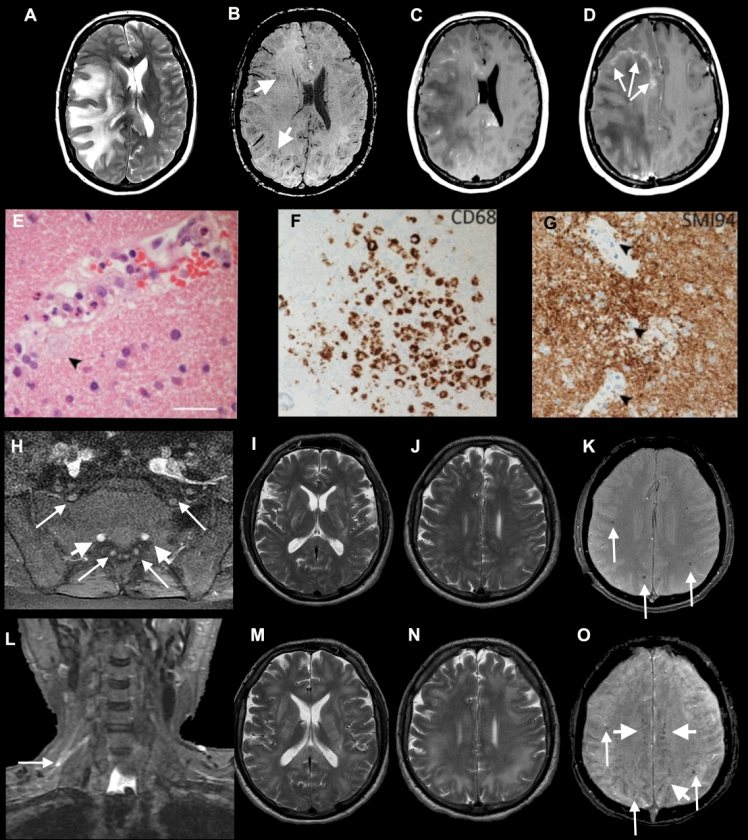

Researchers develop the first objective tool for assessing the onset of cognitive decline through the measurement of white spots in the brain.

In some situations, asking “what if everyone did that?” is a common strategy for judging whether an action is right or wrong.

Researchers explore the “complex web of connections” in your brain that allows you to make split second decisions.

Psychologists W. Keith Campbell, (Ph.D.) and Carolyn Crist explain why narcissists rise to power and how to make sure your support is going to someone making effective, positive change.

Creating a better understanding by clearing up common misconceptions about the neurodiversity movement.

Crows have their own version of the human cerebral cortex.

Would you ever have sex with a robot?

New research conducted on the brains of mice suggest it may be possible to “switch off” particular food cravings.

Are there innate differences between female and male brains?

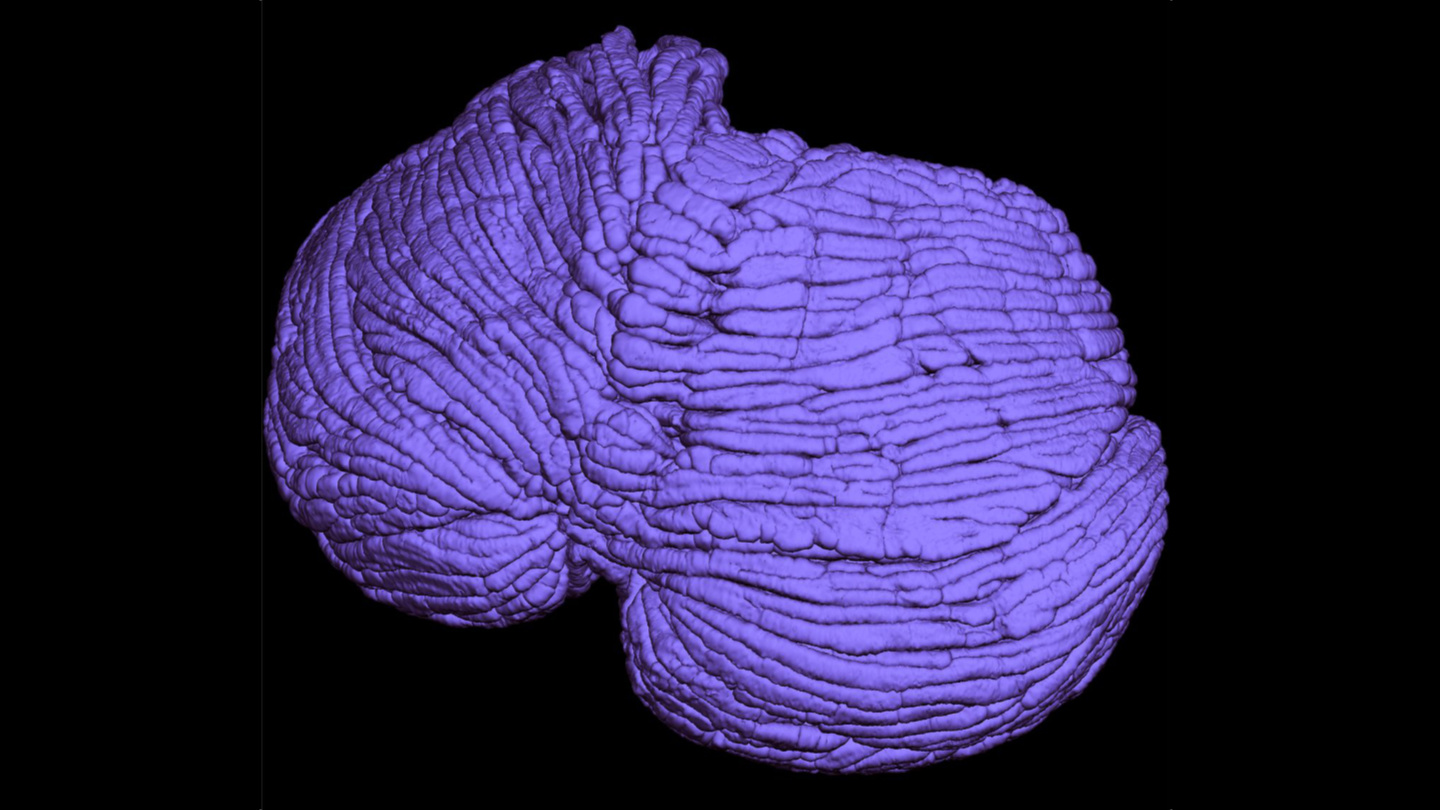

The multifaceted cerebellum is large — it’s just tightly folded.

The 2020 study successfully removed memories associated with morphine from the brains of mice with very promising results.

A growing body of research suggests COVID-19 can cause serious neurological problems.

Human brains evolved for creativity. We just have to learn how to access it.

▸

12 min

—

with

Researchers at University College London link waist circumference with dementia.

A team of scientists in Basel believes this will open up new lines of research.