alzheimer's

New research suggests that there is no “typical” form of Alzheimer’s disease, as the condition can manifest in at least four different ways.

Clinical trials at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research focus on stabilizing cognitive loss and alleviating the psychotic symptoms that change our loved ones.

A Stanford study explores the effect of multitasking on memory in young adults.

Work that can break down the body can also break down the mind.

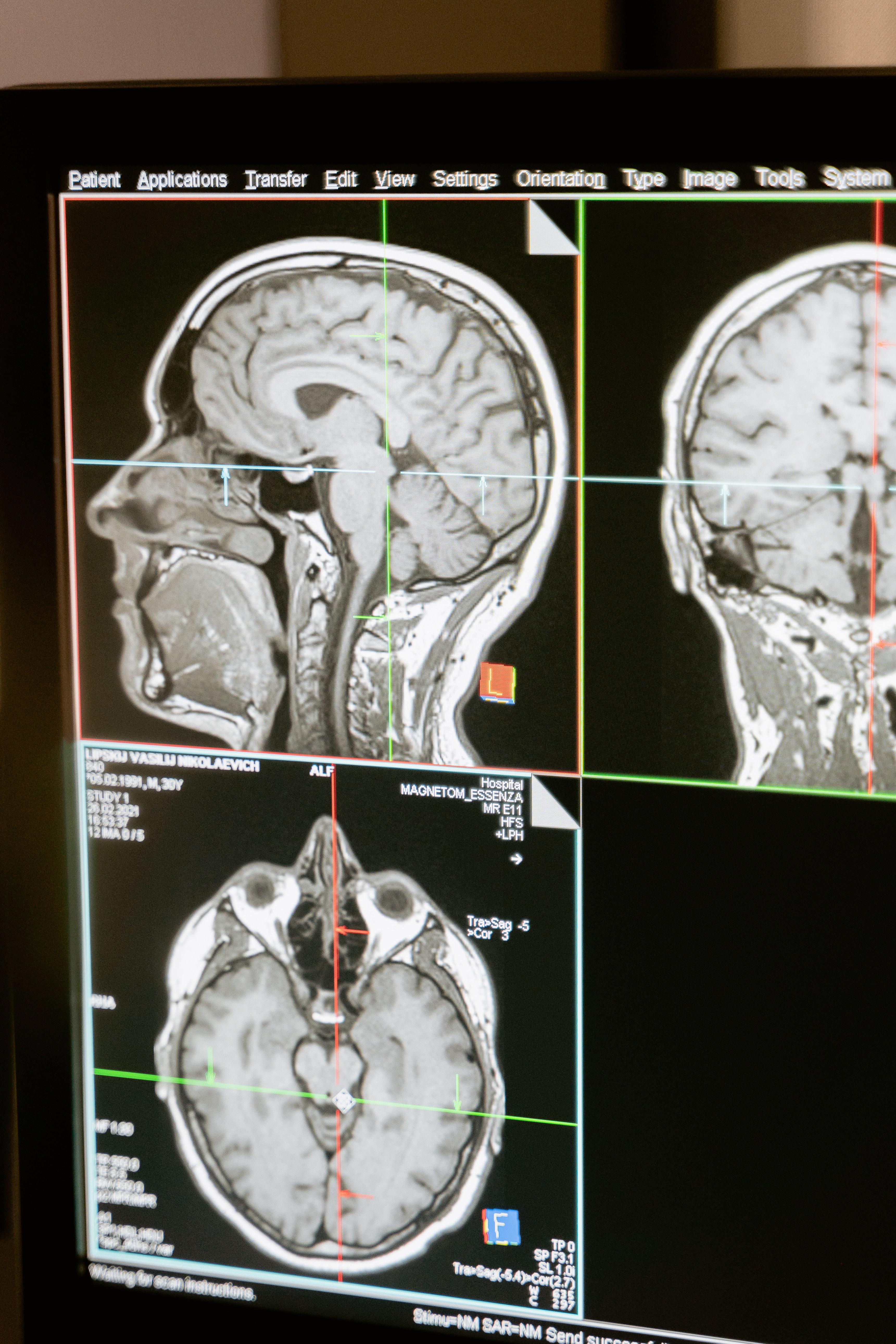

Researchers develop the first objective tool for assessing the onset of cognitive decline through the measurement of white spots in the brain.

We owe a lot to vaccines and the scientists that develop them. But we’ve only just touched the surface of what vaccines can do.

▸

17 min

—

with

Yet 80 percent of respondents want to reduce their risk of dementia.

The number of people with dementia is expected to triple by 2060.

Never has the bar to entry been so low and the recognized benefits so high.

How a study on worms pointed the way towards a treatment for dementia.

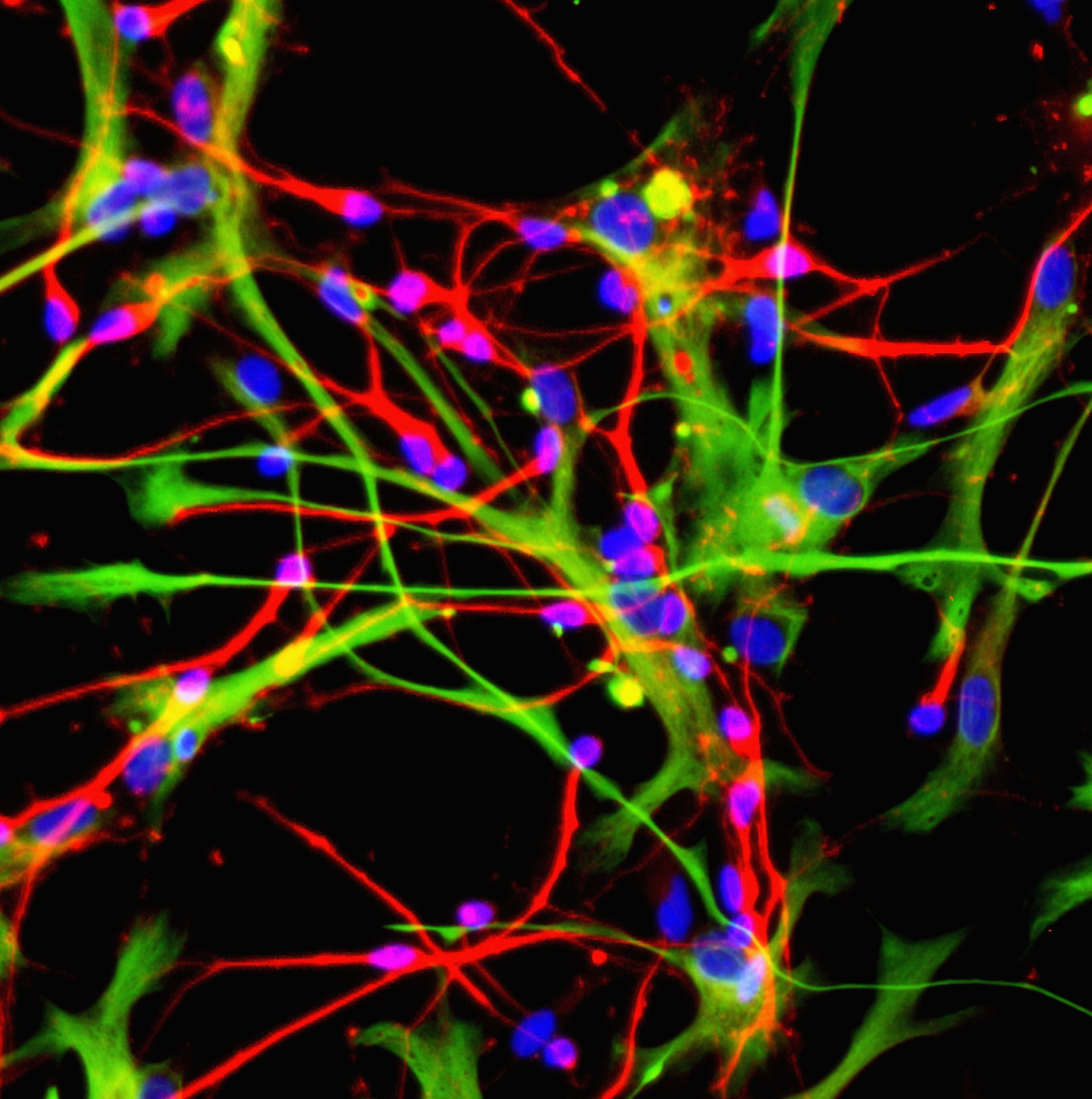

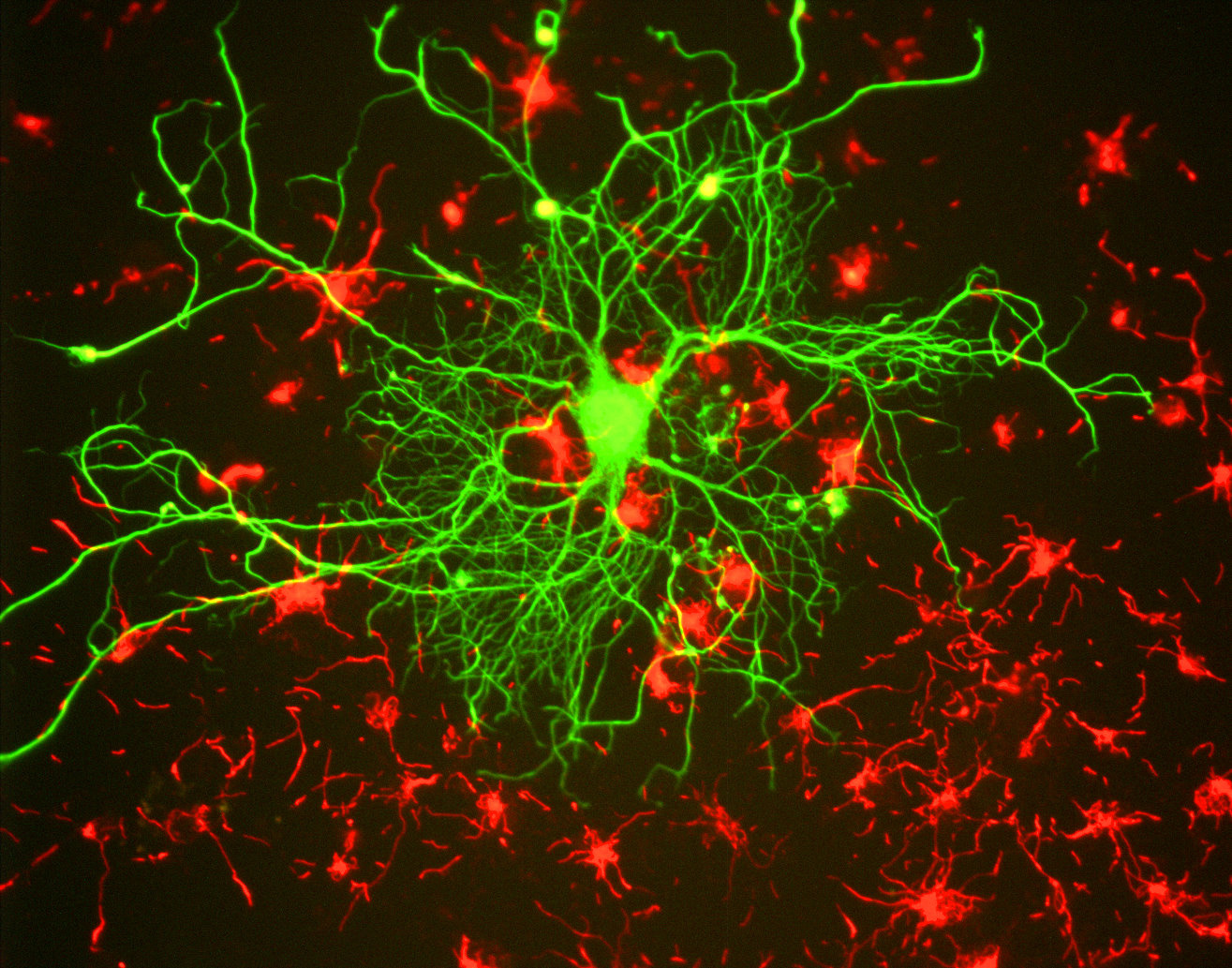

Unraveling the mysteries of adult neurogenesis may have clinical applications.

Researchers at UT Southwestern noted a 47 percent increase in blood flow to regions associated with memory.

A new study from Singapore found that intermittent fasting increases neurogenesis.

The Alzheimer’s Association says its new analysis and surveys “should sound an alarm regarding the future of dementia care in America.”

Your microbiome begins in your mouth. Why don’t we look there more often?

The finding represents one of the first times we have observed how the human brain clears out its waste products.

Sleep deprivation leads to a shutdown in the production of essential proteins.

Most elderly individuals’ brains degrade over time, but some match — or even outperform — younger individuals on cognitive tests.

Why the effects of aging are detrimental to being the U.S. president.

Soon we’ll be able to blink and instantly go online via computer chips attached to our eyes.

▸

3 min

—

with

Studying ‘episodic memory’ in animals may hold the key to understanding memory loss in humans.

Dementia, disrespect, and loneliness – that is not your future, says aging expert Ashton Applewhite.

▸

5 min

—

with

Scientists are developing vaccines for migraines and sciatica (back pain) – a win in the war against the overprescription of opioid drugs.

▸

5 min

—

with

The assumption “that without memory, there can be no self” is wrong, say researchers.

It’s a public health crisis, experts say.

A new study shows promise for epigenetic treatments for humans suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

Some hope for those who are struggling with the disease.

Remaining mentally active slows dementia’s symptoms, if not its progress.