trees

Starting just about now, leaves start changing color from north to south, high to low, light to dark.

Seawater is raising salt levels in coastal woodlands along the entire Atlantic Coastal Plain, from Maine to Florida.

Researchers find that the coffee pulp is valuable in its own right.

Fractal patterns are noticed by people of all ages, even small children, and have significant calming effects.

A study finds 1.8 billion trees and shrubs in the Sahara desert.

We’re in an era of ‘megafires’.

Spending time in green spaces seems to yield many health benefits, most of which researchers are only beginning to understand.

Carbon locked in soils can be emitted by bacteria. Turning up the heat on them releases more carbon.

Some intriguing examples of people grooming the land for the unseen observer above.

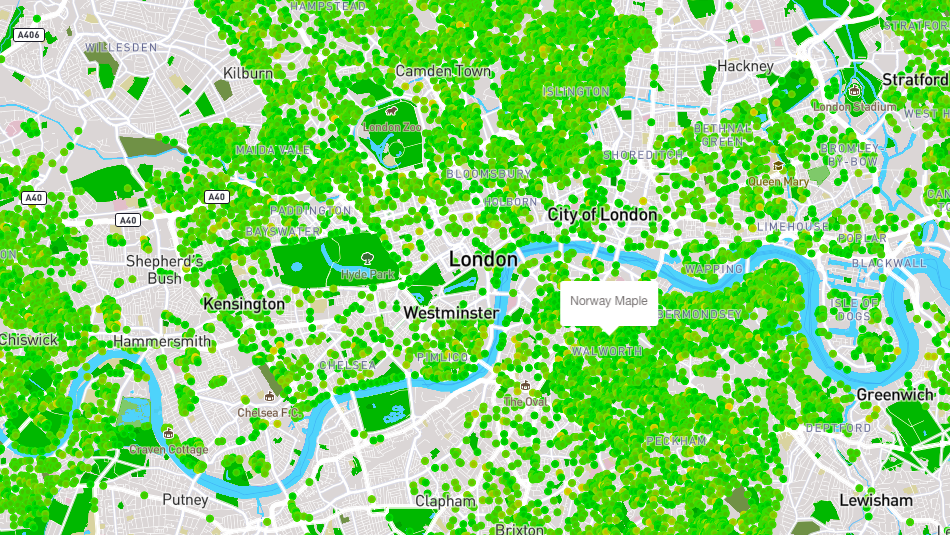

TreeTalk finds rare arboreal treasures among London’s common foliage.

The 385-million-year-old fossils show that trees evolved modern features millions of years earlier than previously estimated.

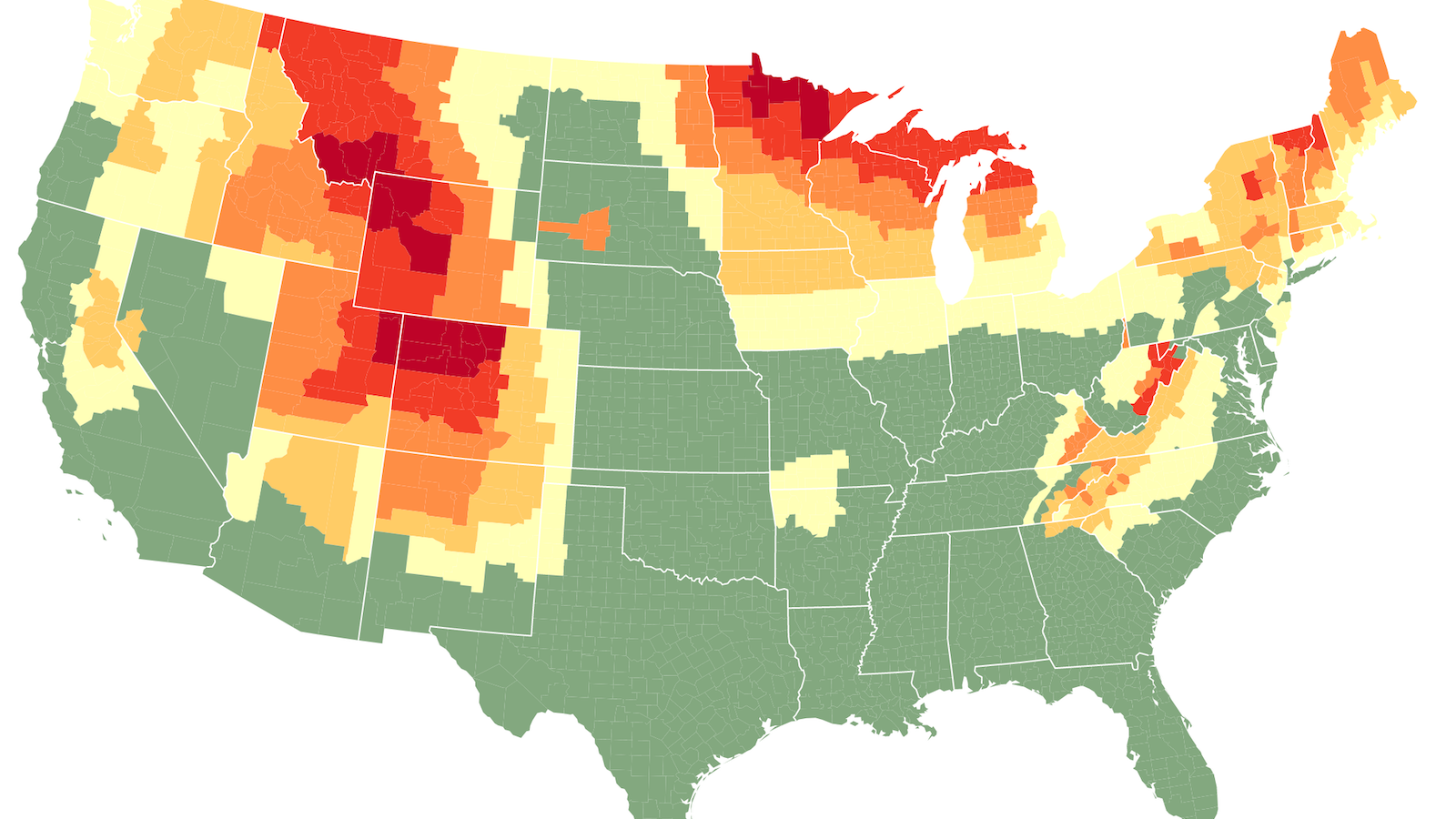

Thinning forests in the Western United States can save billions of gallons of water per year and improve conservation efforts.

Ecosia says the funds generated from users’ searches help to plant one tree every second.

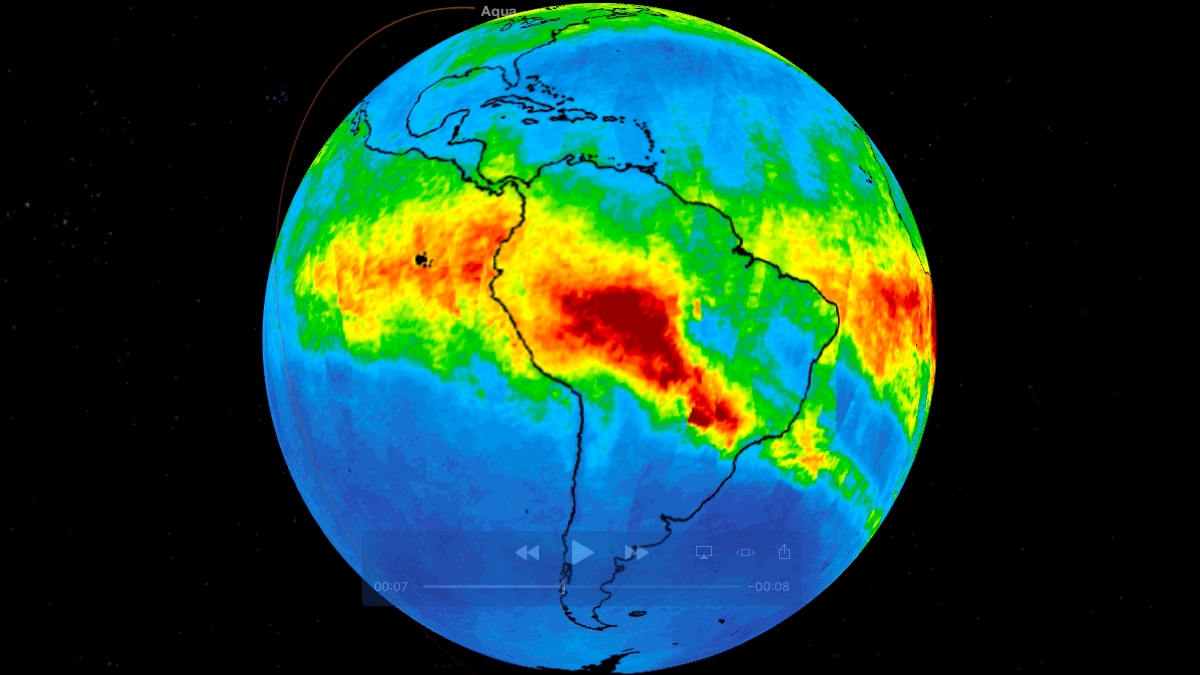

Satellite movie shows clouds of carbon monoxide drifting over South America.

The blazes may be the first step in a hellish downward spiral.

They experience reality differently than we do.

The loss of elephants accelerates climate change.

A new study lays out a green (very green), data-driven plan to capture much of our atmosphere’s carbon pool.

Intense lightning could have burned us out of the trees.

A new paper in Nature adds urgency to the fight against climate change.

Trees are far from dumb; they talk and share, because they need each other to live better lives.