infrastructure

The questions about which massive structures to build, and where, are actually very hard to answer. Infrastructure is always about the future: It takes years to construct, and lasts for years beyond that.

Americans don’t like to ride the bus. There are ways to fix that.

A new study mapped areas of the U.S. that are most likely to suffer natural disasters.

The Kazungula Bridge connects Zambia and Botswana, barely missing Namibia and Zimbabwe.

Some wild animals thrive near humans, but only up to a point.

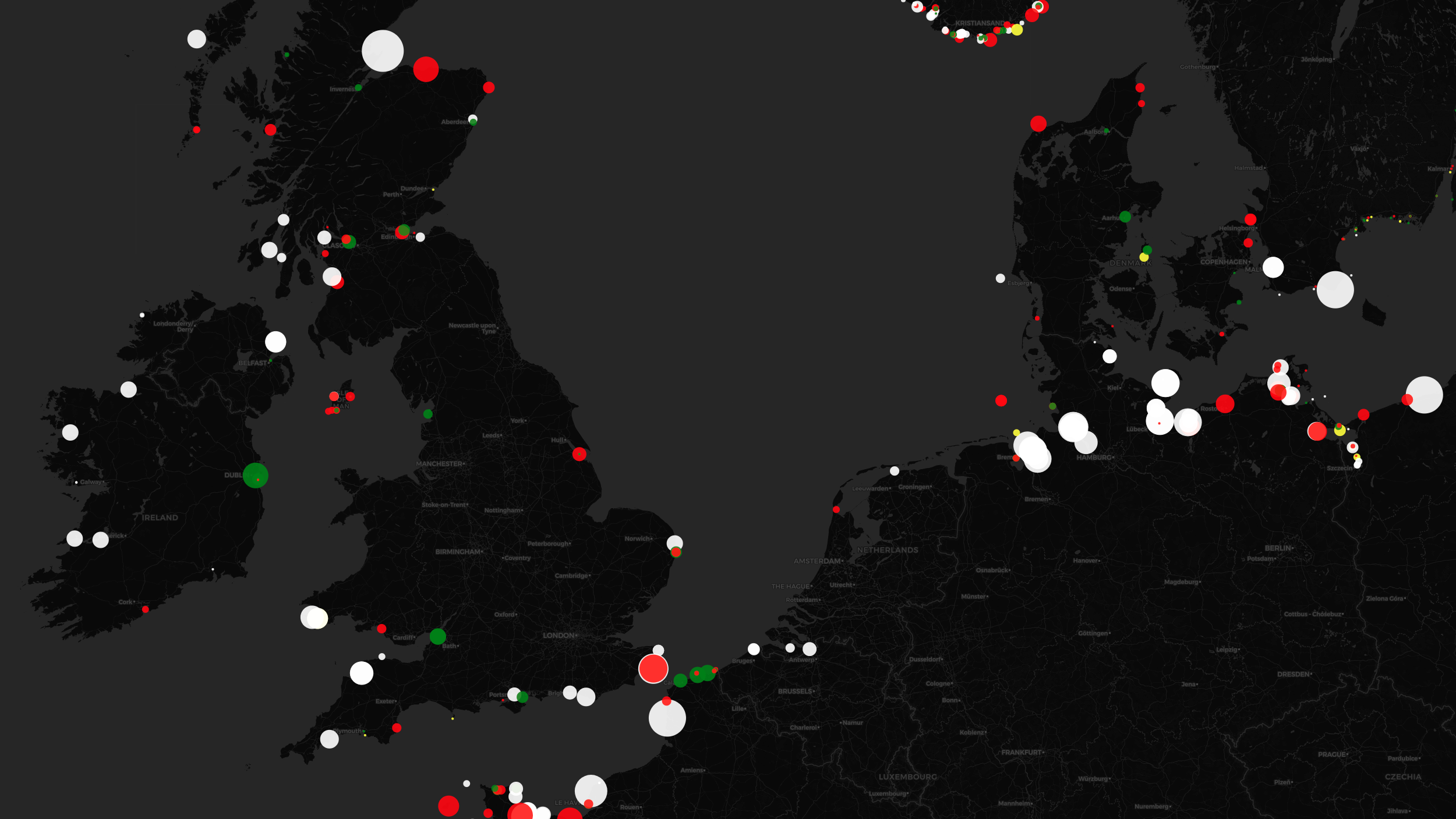

The unique light signatures of nautical beacons translate into hypnotic cartography.

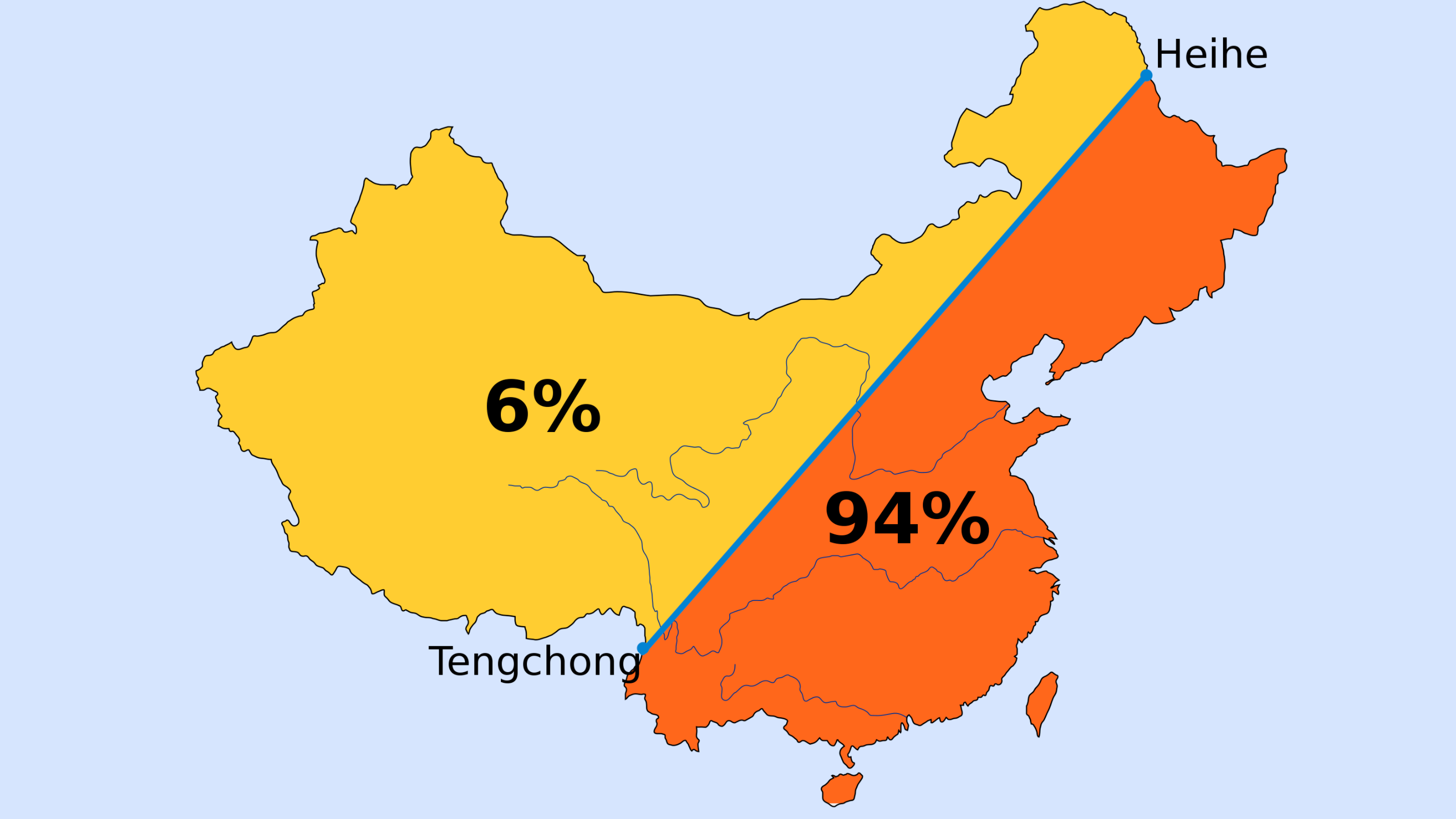

First drawn in 1935, Hu Line illustrates persistent demographic split – how Beijing deals with it will determine the country’s future.

Humans churn out about 30 gigatons (30,000,000,000 tons) of material every year.

Of course, it’s all about where you move. The authors argue that it needs to be less populous regions.

‘Kanal Istanbul’ would create a second Bosporus – and immortalize its creator.

Virtual reality is more than a trick. It’s a solution to big problems.

▸

11 min

—

with

A new study examines the under-researched area of water theft around the world.

Frequent shopping for single items adds to our carbon footprint.

The word “learning” opens up space for more people, places, and ideas.

▸

3 min

—

with

Jordan Hall speculates on the fate of the species.

Answer: When 22 men make more money than all of the women in Africa, an Oxfam study says absolutely.

Cities of the future won’t just be incredibly populated, they’ll also be smarter than ever.

▸

3 min

—

with

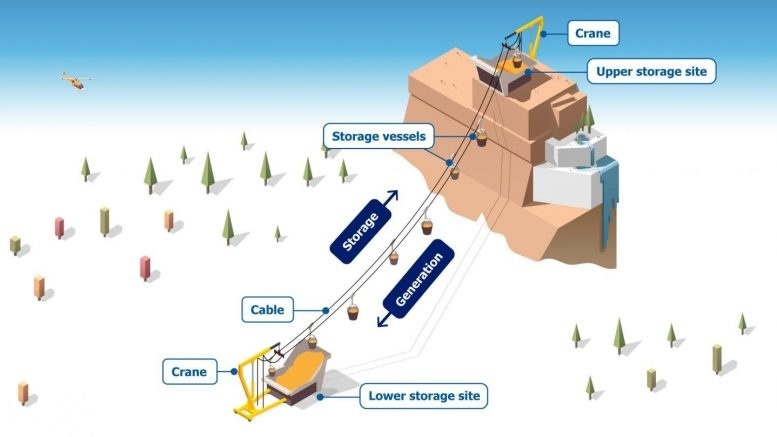

Researchers propose a gravity-based system for long-term energy storage.

Clusters of bot boats may offer cities dynamic solutions to rising waters.

How the half-hour commute and motorised transport changed our cities into huge metropolises.

Humans hate to surrender, but this clearly makes good sense.

An ecological silver bullet is missing the target altogether.

Machine learning, which actively protects you from all sorts of dangers, including fires, explosions, collapses, crashes, workplace accidents, restaurant E. coli, and crime.

▸

with

A new study finds that factors influencing where you’re born continue to affect your earnings throughout life.

Why doesn’t the U.S. generate more electricity from wind?

Ideas are plentiful; execution is another story.

The Ghazipur dump keeps growing and growing every year, catching fire and leaching toxins into the ground. What can be done about it?

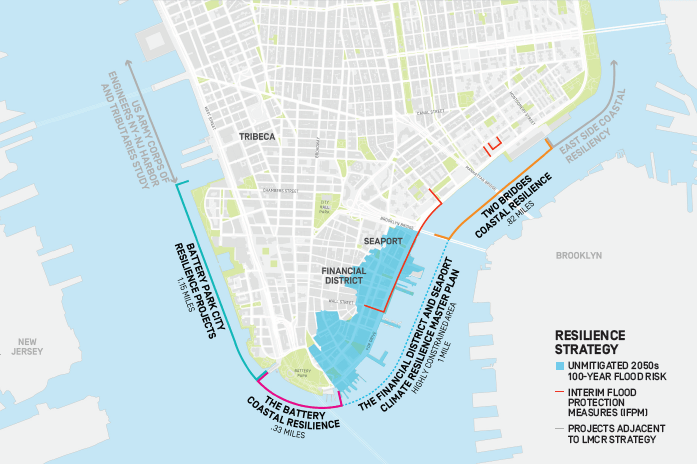

The sea levels across New York are estimated to rise between 18 and 50 inches by 2100.

Humans blame cats for killing birds, but our buildings are far worse.