science fiction

The 1998 hit is making a comeback. Stop what you’re doing and watch the original.

Technology of the future is shaped by the questions we ask and the ethical decisions we make today.

▸

5 min

—

with

“The Expanse” is the best vision I’ve ever seen of a space-faring future that may be just a few generations away.

But most city dwellers weren’t seeing the science — they were seeing something out of Blade Runner.

Thought expriments are great tools, but do they always do what we want them to?

The father of all giant sea bugs was recently discovered off the coast of Java.

Hollywood has created an idea of aliens that doesn’t match the science.

▸

11 min

—

with

Neo’s superhuman powers were only inside of The Matrix. The outside world offered a different reality.

Astronaut Garrett Reisman talks NASA, SpaceX, and where we’re headed next.

▸

4 min

—

with

Through experiencing time in a nonlinear way, can artificial intelligence provide us more perspective?

▸

3 min

—

with

Spoiler: Microbiomes in space!

Baby Yoda merch is on the way, but these Star Wars gifts are available right now.

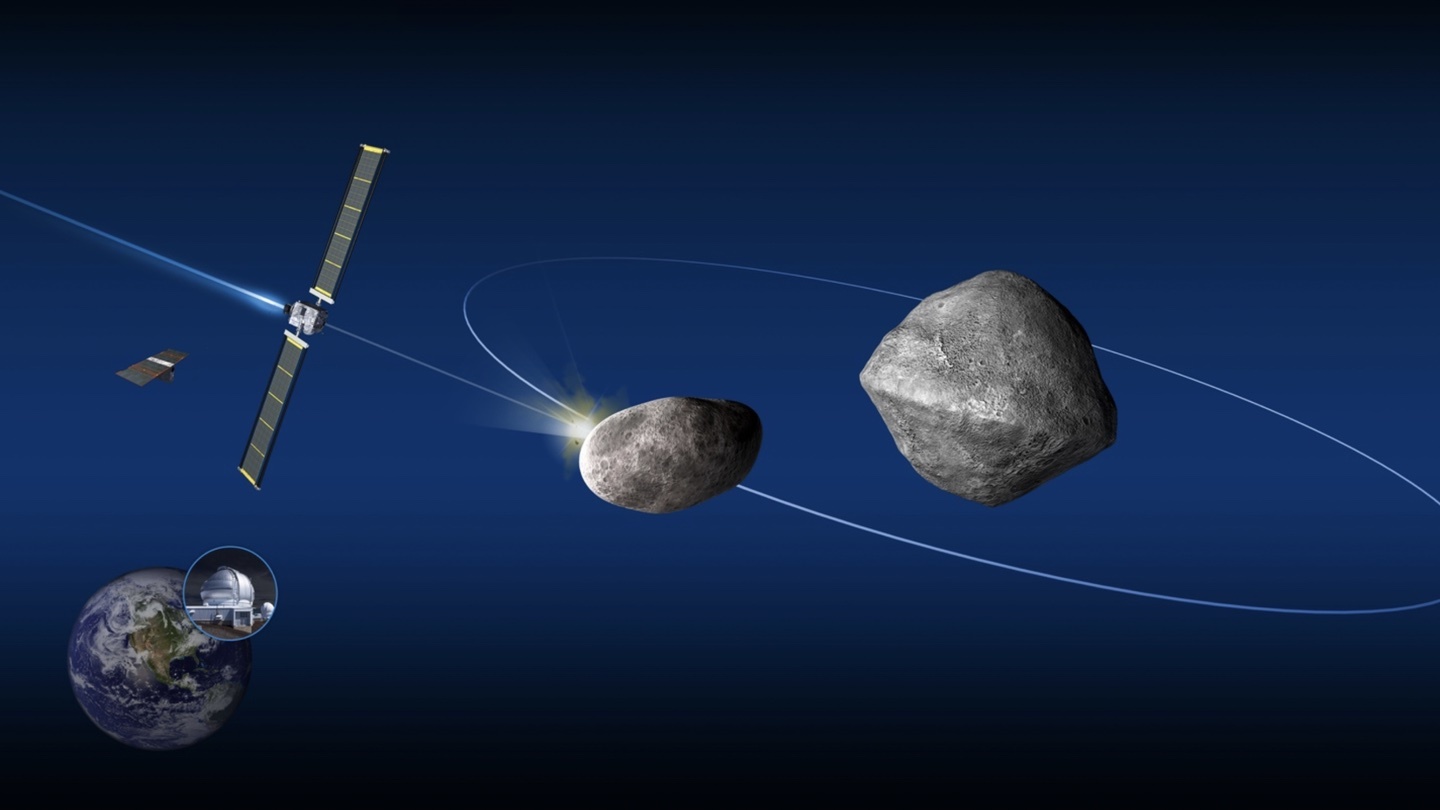

Before the next big, dangerous, incoming rock arrives.

Mother Nature and the laws of physics have a death warrant out for humanity, says Michio Kaku. Can we escape it?

▸

3 min

—

with

Don’t start investing in flux capacitors just yet, though.

The Avengers movies have done a marvelous job melding science and story.

Transport yourself to other worlds and states of mind.

FOIA release sheds light on the DOD’s own struggle to understand UFOs.

Proxima Centauri, our closest star, is more than 4 light years away. Reaching it under 10,000 years will be challenging; reaching it with living humans will be even harder.

Some of them were surprisingly astute.

From the cosmic blast into another being’s mind, to rolling bliss or obedient mind-slavery, fictional drugs have it all.

Breakthrough Starshot is moving ahead with an audacious vision for space exploration.

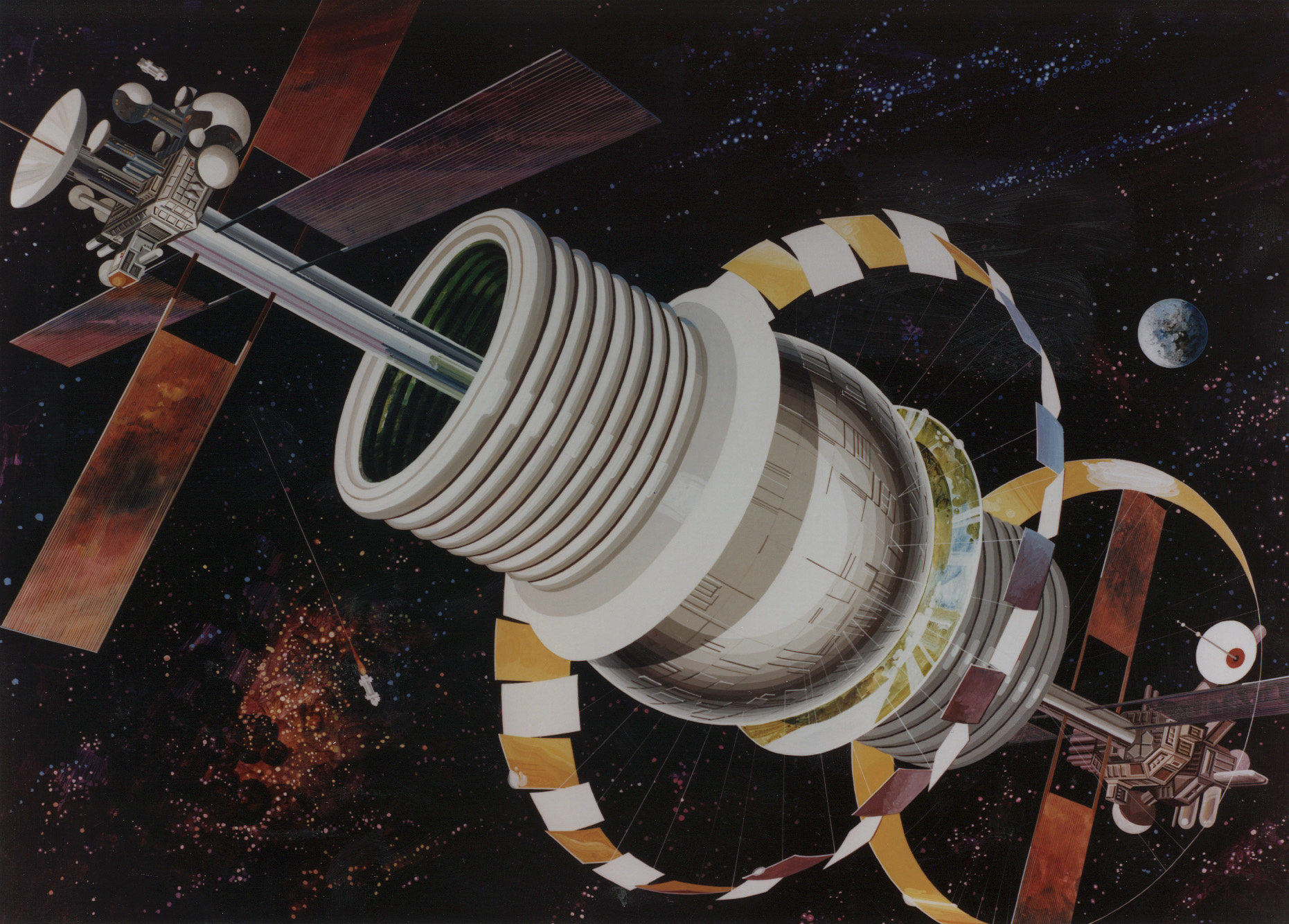

Future or extraterrestrial civilizations could create megastructures the size of a solar system.

Feeling the urge to scare yourself this Halloween? Here are seven important horror films you have to see.

His book warns us of the dangers of mass media, passivity, and how even an intelligent population can be driven to gladly choose dictatorship over freedom.

Like Stevenson, Tolkien and other creators of fantasy worlds, Ursula K. Le Guin was a cartographer as well as a writer

Break out your prospecting gear and space suit.

Researchers succeed in deleting key genes from ants, significantly modifying their behavior.