7 most important horror movies: Double-feature edition

- This scareful season, make sure to check these seven important horror movies off your to-do list.

- Already an aficionado of fear? The list offers a double-feature option to pair with each classic horror flick.

- With apologies to Hereditary, but I haven’t seen it yet.

It’s October! That time of year when we are duty bound to indulge in horror movies till we can’t sleep with the closet door ajar. If you’re looking to indulge your horror habit, we’ve collected seven of the most important horror movies to check off your watchlist.

For those who have already perused the gothic spires and haunted hallways of these classic terrors, we’ve paired them with films equally deserving of classic status. Each double-feature shares a particular quality, whether thematic, atmospheric, or cinematographic.

Here are our seven most important horror films (and their double features).

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Le Manoir du Diable

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) represents the best of silent horror. Director Robert Wiene created a German expressionist nightmare with his scenery of vulgar angles and jagged pathways. The story revolves around the titular Dr. Caligari, who uses the sleepwalker Cesare to commit murders. When Cesare kills a villager named Alan, the pursuit of truth eventually leads to the madhouse.

As Roger Ebert writes in his review of the film: “A case can be made that ‘Caligari’ was the first true horror film. There had been earlier ghost stories and the eerie serial ‘Fantomas’ made in 1913-14, but their characters were inhabiting a recognizable world. ‘Caligari’ creates a mindscape, a subjective psychological fantasy. In this world, unspeakable horror becomes possible.”

Looking to make a silent evening of it? Then consider Le Manoir du Diable(1896), directed by the inimitable George Méliès. Méliès’ short film may be the oldest extant horror film, and it comes with all the trappings: transforming bats, bubbling cauldrons, and demonic tricksters.

But in tone, it could not be more different from Caligari. Whereas Caligari is brooding and unnerving, Méliès’ film is a vaudevillian magic show that uses editing to mischievous effect. At just over three minutes, you can also enjoy this piece of horror history on a short coffee break.

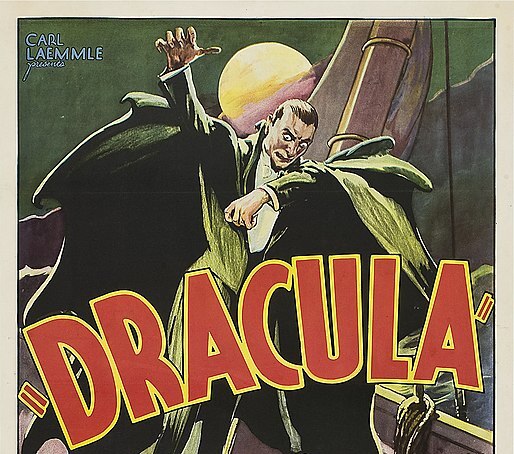

The Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

The Bride of Frankenstein and The Cat People

Many of Carl Laemmle Jr.’s horror movies at Universal deserve a place on this list, but the series’ crown jewel is The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). After Henry Frankenstein and the monster survive the conflagrated windmill, Henry’s mentor, Dr. Pretorius, arrives and forces Henry to begin creating a mate for the Monster, who seeks a friend and confidant.

Director James Whales builds on the excellent foundation of the first Frankenstein (1931) with Gothic architecture that is as grandiose as it is decrepit. Boris Karloff brings even more empathy to the monster this go around, and the bride makes an indelible impression despite her minuscule screen time.

To round out the evening, try Jacques Tourneur’s The Cat People(1942). The film tells the story of Irena, a woman who believes she will turn into a man-eating cat if aroused or angered. (Trust us, it’s better than it sounds.) Despite a limited budget, The Cat People parallels Bride of Frankenstein in using knife-edged shadows to build suspense and atmosphere. They are also thematically linked over concerns of loneliness and sexual exclusion.

Psycho (1960)

Psycho and The Haunting

Despite directing Vertigo, Rear Window, North by Northwest, and a slew of other classics, Alfred Hitchcock’s most successful film is Psycho (1960). It’s arguably the first slasher film, and even if it’s technically not, a genre pedigree would show it is the father to such gruesome tykes as Black Christmas, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and Halloween. (Their mother would be the Italian giallo films. Hey, it was the sixties).

Do I even need to discuss Psycho? The film’s mark on our culture, with its vivid imagery and shrill soundtrack, has made it perhaps the most parodied and alluded to movie in history. And that’s a shame because Hitchcock wanted the film’s twists and turns to surprise each first-time viewer. Well before the days of netiquette, he devised a set of rules to prevent spoiler warnings, including tight schedules, controlled media buzz, and no late admissions permitted.

Not as well-known, but no less deserving of classic status, is Robert Wise’s The Haunting(1963). Based on Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House, the story follows two women with purportedly psychic abilities, Eleanor and Theodora, who are invited to live at the haunted Hill House by a scientist wishing to investigate its mysteries.

Both movies trade in anxiety-inducing settings. Like the Bates house, Hill House is claustrophobic despite its size. But The Haunting‘s terrors are more abstract. Is the house haunted or are the nightmarish happenings the result of Eleanor’s deteriorating mental health?

Interestingly, both of these films were remade in the ’90s. You can skip those.

The Babadook (2014)

The Exorcist and The Babadook

William Friedkin’s The Exorcist(1973) may be the scariest movie of all time, and this reputation has been bolstered by the many deaths associated with its production, leading to the claim that the film was cursed.

After playing with a Ouija board, young Regan begins to display erratic, vulgar behavior. After consulting a number of physicians, Regan’s mother asks Catholic priests to perform an exorcism. But the demon isn’t going to give up Regan’s soul quietly.

Have you ever seen a demonically possessed child cirque du soleil her way down the stairs? No? Then watch The Exorcist.

If you can uncurl yourself from the fetus positions, you could put on The Babadook (2014) next. In it, Amelia Vanek must raise her son, Samuel, alone after her husband’s death in a car accident. Emotionally and physically exhausted, she becomes the target of a monster, demon, whatever called Mister Babadook. But Babadook can’t do his grisly deeds himself, and must possess Amelia if he is to have Samuel.

Both films elicit visceral responses in how they put the most vulnerable among us, children, in danger of physical and mental harm. But while The Exorcist‘s dangers come from a malicious spirit—evil’s got to evil, yo—The Babadook‘s danger comes from the person tasked with caring for Samuel.

Alien (1979)

Alien and It Follows

Fear is an intimate emotion, and no other film portrays that fact better for me than Alien (1979). You never forget your first.

Directed by Ridley Scott, Alien follows the crew of the USCSSNostromo as they investigate a mysterious transmission and accidently let loose a deadly alien aboard their ship. While later sequels rendered the alien just another monster of the week—a less loquacious Zerg—the original’s incarnation continues to terrify.

This is partly due to technical limitations forcing Scott to never show it in full. Instead, dark angles and quick cutaways show just enough for your imagination build the rest. But we can’t discount H.R. Giger’s unsettling design. Sometimes an alien head is just a cigar, but in this case it’s definitely a killer penis.

A film that pairs remarkably well with Alien is David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014). In it, a girl named Jay sleeps with her boyfriend only to be cursed by the sexual encounter. A shape-shifting creature will now stalk her until either it kills her or she passes on the curse by sleeping with another.

Both movies deal in sexual horrors, but while Alien‘s monster is a symbol of sexual perversion and evolutionary conquest, It Follows takes a different approach. Jay’s is a coming-of-age story. Her monster is the world at large, where natural drives like sex can provide pleasure but also disease, anxiety, and moral compromise.

The Witch (2015)

The Shining and The VVITCH

We all knew The Shining (1980) was going to be here, right? Stanley Kubrick’s film is a horror masterclass of unnerving tension.

What more can be said? Jack Nicholson crushes it as, erm, Jack. The imagery has been indelibly seared into our cultural consciousness. Even the carpet has been analyzed to death. But it’s Kubrick’s use of perspective that makes the film so terrifying, especially with regard to the young and vulnerable Danny.

A good modern pairing for The Shining is The Witch (2015). The Witch tells the story of a colonial family forced to leave the protection of the settlement due to religious differences. Living in the wilderness, they are preyed upon by a coven of witches.

Both movies deal with families in isolation and children harmed by the demons inherent in their guardians. The Witch uses this setup to speak toward the problem of evil. Why would a caring, benevolent god allow them to suffer despite their professed love for him?

Kubrick’s film doesn’t ask the question so directly, yet it should be noted that no outside force comes to save the Torrance family from its patriarch (Scatman Crothers notwithstanding).

The Thing (1982)

The Thing and Get Out

When John Carpenter’s The Thingwas released in 1982, critics and audiences called it cynical, disturbing, nihilistic, and all around unpleasant. Today, it’s the film cinephiles point to when pining for the days of practical effects and R-rated horror. Go figure.

The Thing opens with American researchers in Antarctica explore the remains of a destroyed Norwegian research station. The only survivor of the Norwegian station, a sled dog, is revealed to be a shape-shifting alien that can imitate any form. To survive, the researchers must kill the creature, which could be any one of them.

Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) pervades a similar sense of paranoia. Peele’s film tells about an African-American man, Chris, spending the weekend with his white girlfriend’s upper-class family. While The Thing is about fearing a hidden malevolence within the group, Get Out portrays the group itself as the terrifying presence.