intelligence

We are ~99% genetically identical to chimpanzees. But there are three key traits that separate us.

▸

6 min

—

with

Carl Jung was one such person.

A female boar’s intelligence, resolve, and empathy stun researchers.

When you unintentionally step on a dog’s tail, does it know that it was an accident?

A new study refutes some of the claims recently made about the value of napping.

Australian parrots have worked out how to open trash bins, and the trick is spreading across Sydney.

Research shows that those who spend more time speaking tend to emerge as the leaders of groups, regardless of their intelligence.

Eight-eyed arachnids can tell when an object’s movement is not quite right.

The opening of jars, while impressive and often used to illustrate octopus intelligence, is not their most remarkable ability.

Maybe eyes really are windows into the soul — or at least into the brain, as a new study finds.

Being an intellectual is not really how it is depicted in popular culture.

▸

5 min

—

with

We can’t ask them, so scientists have devised an experiment.

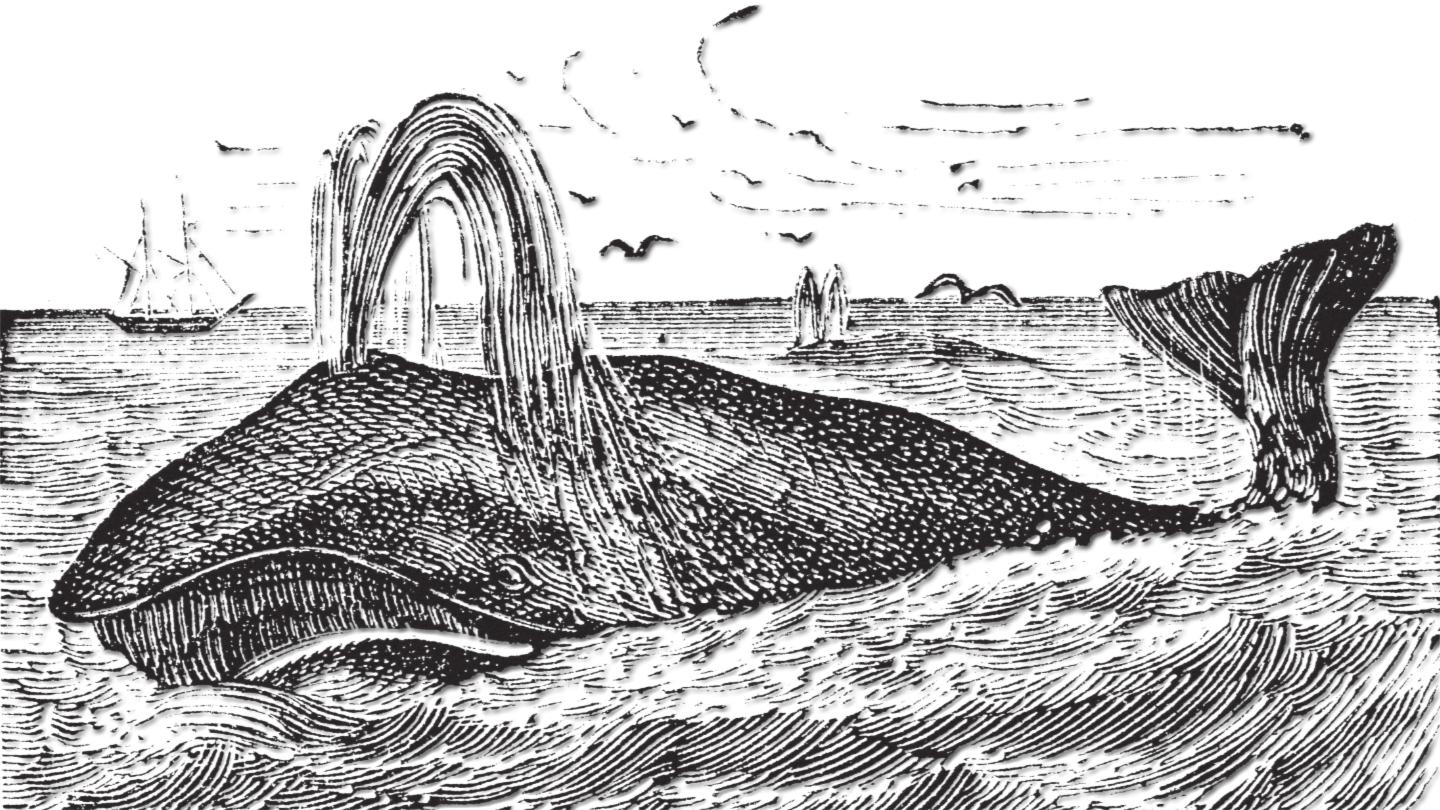

Digitized logbooks from the 1800s reveal a steep decline in strike rate for whalers.

Labeling thinkers like Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs as “other” may be stifling humanity’s creative potential.

▸

14 min

—

with

The famous cognition test was reworked for cuttlefish. They did better than expected.

They did really well considering joysticks are not designed for oral use.

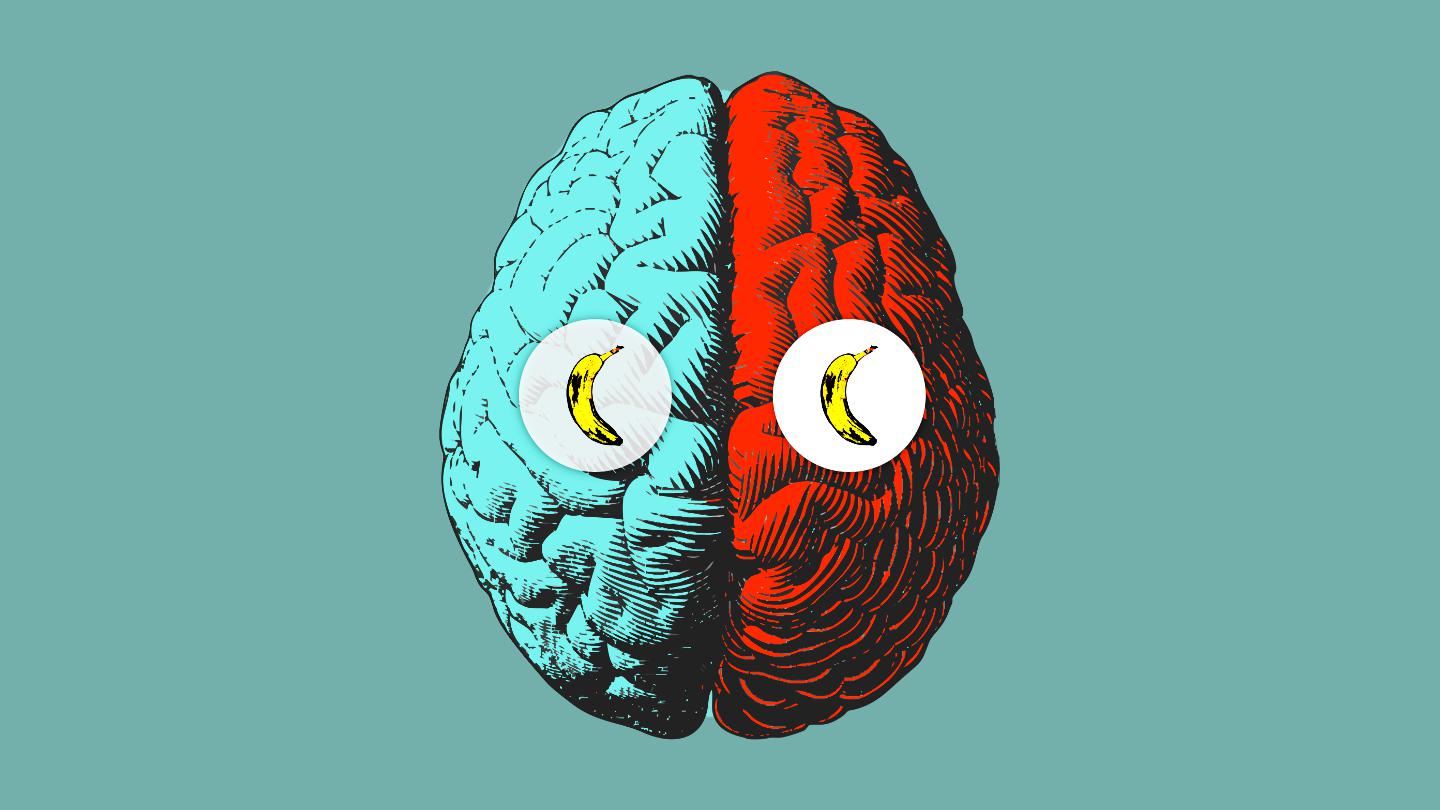

Scientists observe how the halves of the brain keep us informed about everything everywhere.

A recent study showed that monkeys can make logical choices when given an A or B scenario.

Let noted cognitive psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker introduce you to psychology.

When someone is lying to you personally, you may be able to see what they’re doing.

Psychologists point to specific reasons that make it hard for us to admit our wrongdoing.

Max Planck Institute scientists crash into a computing wall there seems to be no way around.

A large study shows changes in the brain scans of lonely people in the area involved in imagination, memory, and daydreaming.

Research shows that sparrows and other animals use plants to heal themselves.

These tiny fish are helping scientists understand how the human brain processes sound.

Recent research shows that brain teasers don’t make you smarter and don’t belong in job interviews because they don’t reflect real-world problems.

A growing body of research suggests COVID-19 can cause neurological damage in some patients.

Think you can solve it? One mathematician has already offered about $1,000 and a bottle of champagne to whoever cracks it first.

Researchers explore the “complex web of connections” in your brain that allows you to make split second decisions.

Creating a better understanding by clearing up common misconceptions about the neurodiversity movement.