Anthropology

He lived with a tribe of hunter-gatherers to witness how an ancient culture survives one of the most brutal climates on Earth. His learnings may surprise you.

▸

8 min

—

with

For decades, researchers have proposed that climate change and human-caused environmental destruction led to demographic collapse on Easter Island. That’s probably false, according to new research.

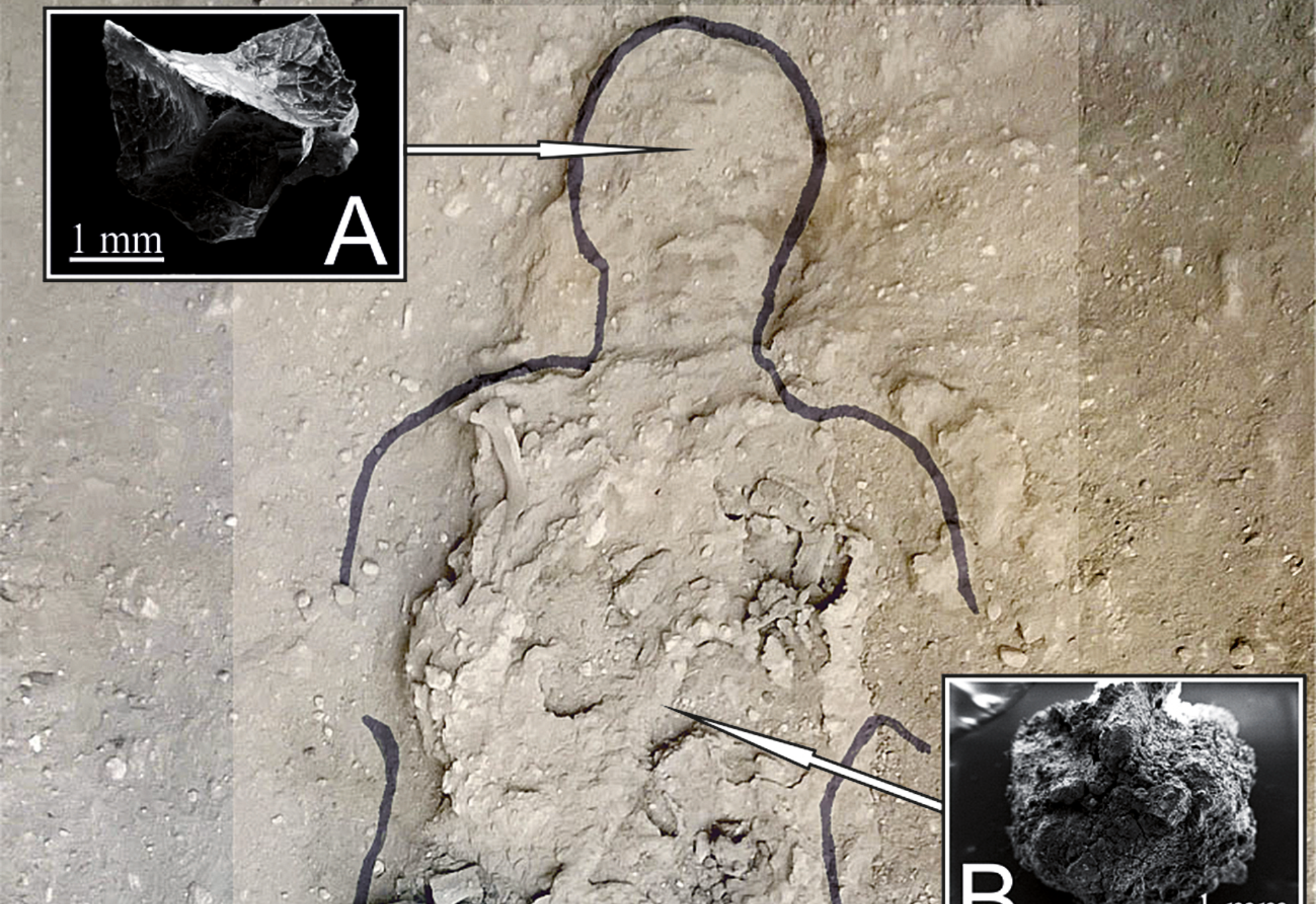

How do archaeologists know if someone was buried intentionally tens of thousands of years ago?

After years of speculation a team of researchers has pinpointed the age of this ancient mystery.

“Large-scale indiscriminate killing is a horror that is not just a feature of the modern and historic periods, but was also a significant process in pre-state societies,” the researchers wrote.

Research shows that bone fragments of Jesus’s (possible) brother belong to someone else.

While other factors exist, sexual prowess appears to have helped determine the role of Protoceratops frills.

Traces of heroin and cocaine have been found in the tartar of 19th-century Dutch farmers.

New anthropological research suggests our ancestors enjoyed long slumbers.

Two new studies shed light on who first inhabited the islands, who replaced them, and how few people lived there.

Carbon dating allows us to know exactly when ice was melted for drinking water in pre-Columbian America.

A new study shows that at least one long-ago journey would have required deliberate navigation.

The rites we give to the dead help us understand what it takes to go on living.

Rare structures and artifacts of the Viking religion practiced centuries prior to Christianity’s introduction have been uncovered by archaeologists in Norway, including a “god house.”

Researchers found a common element in the destruction of even the most powerful empires.

The young man died nearly 2,000 years ago in the volcanic eruption that buried Pompeii.

Scientists have found evidence of hot springs near sites where ancient hominids settled, long before the control of fire.

“The results change the perception of who a Viking actually was,” said project leader Professor Eske Willerslev.

Two anthropologists question the chemical imbalance theory of mental health disorders.

Having lots of kids is great for the success of the species. But there’s a hitch.

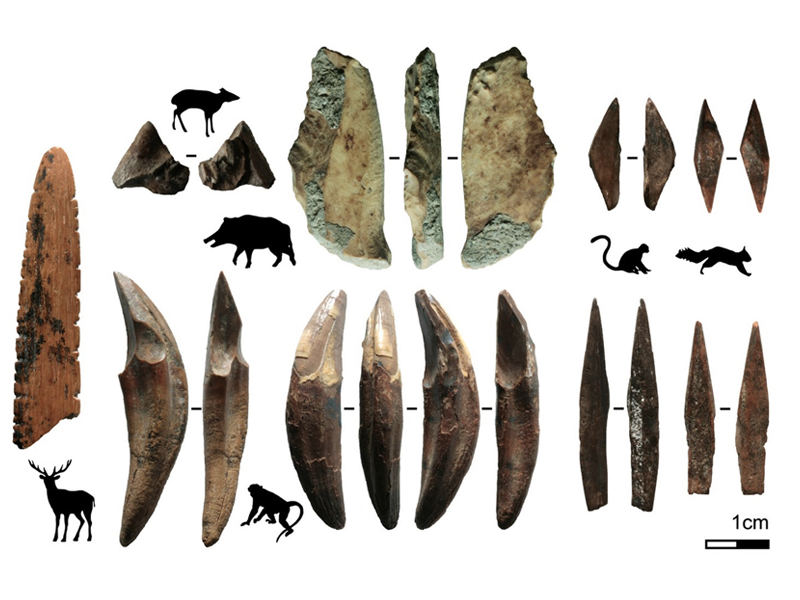

Artifacts uncovered in southeast Asia offer clues on early complex human cultures.

Inbreeding leads to a problematically small gene pool.

We’d like to think that judging people’s worth based on the shape of their head is a practice that’s behind us.

The discovery may change what we know about early humans in Europe.

Many of the bathrooms uncovered at Pompeii and elsewhere were communal.

A new finding suggests Neanderthals were far from the big dumb brutes we make them out to be.

Because geocaches are always hidden out of sight, players often have to behave in out-of-the-ordinary ways to reach them.

What if patience, and maybe other personality features too, are more a product of where we are than who we are?

A review of Matthew Engelke’s How to Think Like an Anthropologist.