Ancient Puebloans used ice caves to survive droughts

Credit: pisotckii / Adobe Stock

- A new study shows that ancient peoples in the American Southwest were using the same caves to collect ice for a millennium.

- The dates of their collection activities line up with tree-ring records of drought events in the area.

- The ice in the cave is melting, and studies on other possible collection events must occur soon before the evidence vanishes.

Living in the desert isn’t easy. Being defined by lacking water, the one thing everybody needs at least every couple of days, groups of people who live there are known for coming up with a wide variety of methods of maximizing the water they have and minimizing the amount they waste.

It should not surprise us then that the ancestors of the Pueblo people of the American Southwest had more than a few tricks up their sleeves. Starting nearly two thousand years ago, they were spelunking in caves so cold, winding, and deep that ice was available year-round, providing a safeguard in the event of drought. A recently released study in Nature sheds light on their methods and even provides us with these collection events’ dates.

Researchers led by Bogdan P. Onac of the University of South Florida investigated an ice core collected from a lava tube in a cave in El Malpais National Monument. Known as Cave 29, the cave is chilly and structured so that it doesn’t allow warm air from the outside to reach the lowest recesses easily. This enables water ice that accumulates there to remain frozen year-round. It is of considerable size and likely held an ice deposit of roughly 1000 m3 at some point.

The team drilled a 59cm long ice core out of an ice deposit. Even a glance at it shows darkened areas where ash and charcoal buildup occurred from nearby wood burning. Radiocarbon dating allowed the scientists to place these burn dates roughly at the years AD 167, AD 368, AD 747, AD 829, and AD 933.

These years are known to have been years of drought in the Southwest, suggesting that ancient people ventured into the cave searching for ice to melt into drinking water on each occasion over a millennium. In the cave’s lower depths, one can also find charred wood, old torches, charcoal, and other evidence of controlled burning.

The implications of the study have excited anthropologists. Barbara Mills, an anthropological archaeologist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the study, explained to Science News:

“This study demonstrates the ingenuity of indigenous people who used the area. It also shows how knowledge about the trails, caves and harvesting practices was passed down over many centuries, even millennia.”

While previous studies proved that pre-Columbian peoples in the Americas turned to melting ice from lava tubes for water, this study appears to have pushed back the earliest known occurrence.

The ice block the core was taken from, still covered in ashes. The close up shows a piece of pottery next to burned pieces of wood. Credit: Scientific Reports

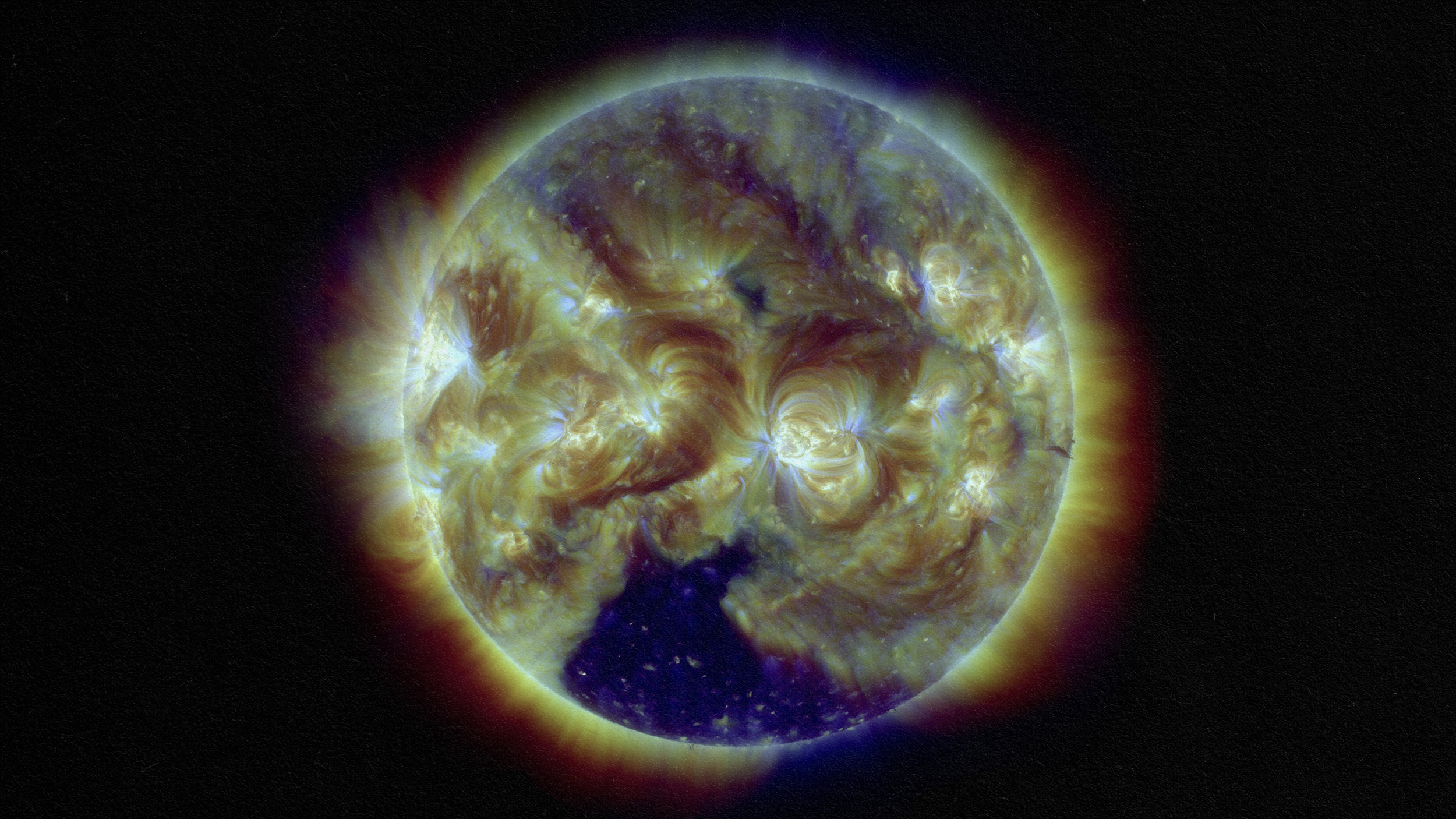

Tree rings can be used to learn the meteorological history of an area. As trees grow outward, new rings appear inside their trunk, taking on differing appearances with changes in the environment. By looking at these rings, scientists can get an idea of what conditions were like in ages past.

By comparing the radiocarbon dating of the charcoal samples with the tree rings, a pattern emerges. The periods the samples date back to correspond to the same periods when droughts appear in the local tree ring record. This provides powerful evidence that the burning was taking place during droughts to collect water.

The scientists also note that some of these collection events match the time of the medieval warm period drought, which is known to have occurred during continuous periods of La Nina conditions and negative Pacific Decadal Oscillation; both of which are known to cause drought conditions in the Southwestern parts of the United States.

These events affect large areas of the world and are recorded by tree rings from many places, not just the American Southwest. Combining these records lends further credence to the idea that the burnings were tied to drought periods.

While the authors admit the possibility that the burned wood samples could be the result of wildfires, which were then blown or swept into the cave by natural forces, they point out that this is unlikely. The lack of air circulation nearly rules out anything being blown into the lower reaches of the cave, and that the concentration of ash in some areas combined with an utter lack of it in others points strongly towards human intervention- if the ashes blew in, you’d expect some of it to get everywhere.

Thus, they conclude that these findings are “unambiguous evidence” that this is evidence of people melting ice for their own purposes rather than a natural occurrence.

Precisely what the people of over a thousand years ago thought when they went to these caves is also the realm of speculation. While it is clear that people were collecting the water during drought periods, the water’s ceremonial or medicinal use cannot be ruled out. Indeed, the archaeologist and member of the Ashiwi people of the Pueblo of Zuni Kenny Bowekaty explained to E&E news that the ice caves did serve a religious purpose in addition to the others they had.

The study focused on a single lava tube’s contents, and further studies may find evidence of other collection events. They will have to take place soon, though. Increasing global temperatures are causing cave ice to melt and for records of ancient events to disappear forever.