anthropocene

A new paper explores how noise from human activities pollutes the oceans, and what we can do to fix it.

In a joint briefing at the 101st American Meteorological Society Annual Meeting, NASA and NOAA revealed 2020’s scorching climate data.

Researchers document the first example of evolutionary changes in a plant in response to humans.

The complacent majority needs to step up and call for action on climate change.

▸

22 min

—

with

Animals are adapting all the time these days to stay out of our way.

Today’s agriculture workers face 21 days of heat that exceed safety standards. That number will double by 2050.

We’ve known this virus was coming. We just didn’t do anything about it.

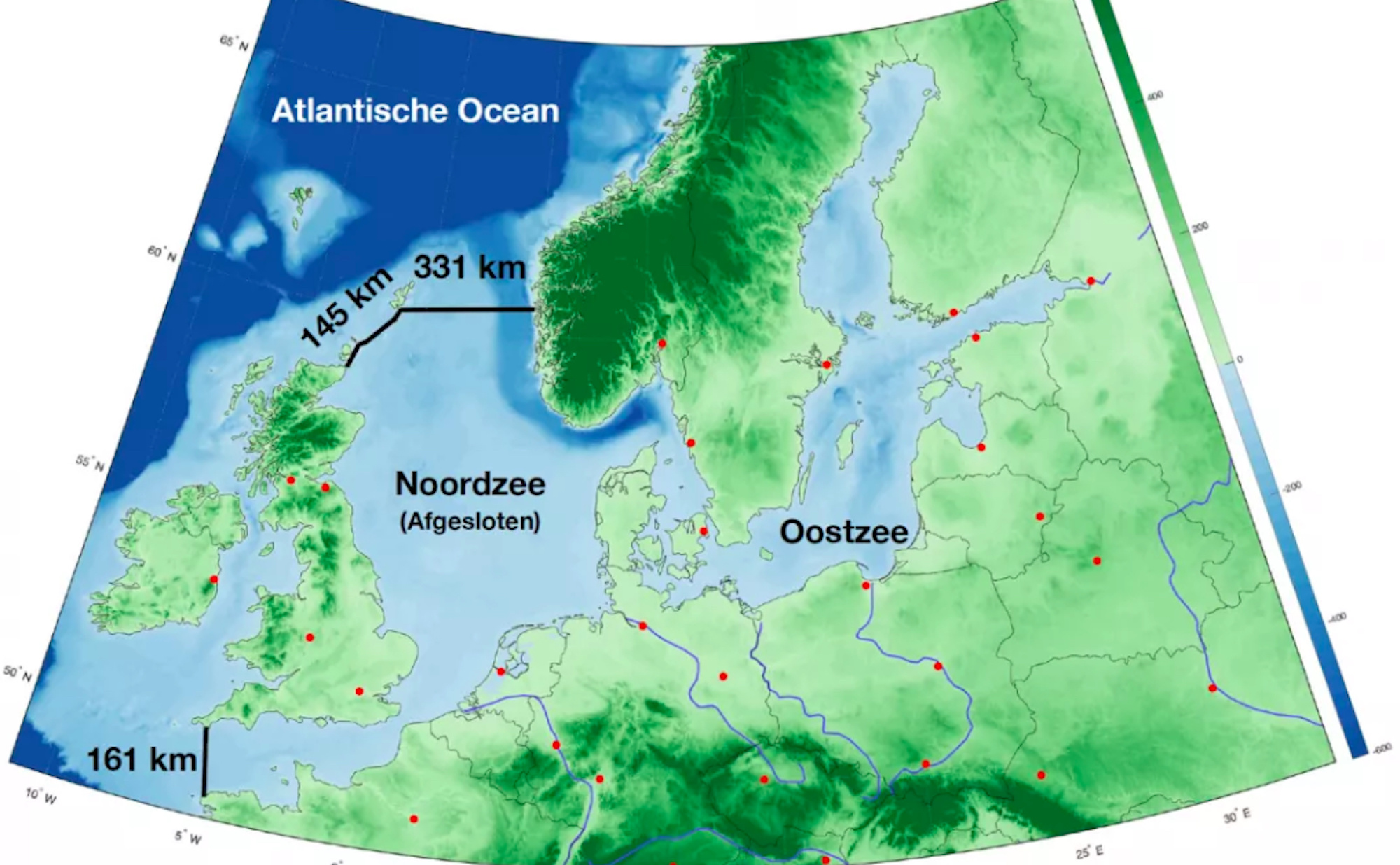

Why a 400-mile enclosure around the North Sea is not as crazy as it sounds

Hundreds more are documented in Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks.

Fast fashion has a devastating impact on the environment. Here’s what you need to know before heading to Zara this holiday season.

Rather than scrubbing the emissions from fossil fuel plants, a new analysis suggests we should simply replace those power plants with renewable alternatives.

While the blockbuster franchise might have given us a distorted view of science’s capabilities to address species extinction, new research might come close to “resurrecting” lost species’ DNA.

Glenn Albrecht has ideas about how to cope with the effects of a changing world: Invent a new language.

Fauna and flora refuse to go quietly into the Anthropocene.

Bats are being subjected to a deadly plague that may be threatening their existence. However, a new bacterial spray may help fight the fungus responsible.

A new study lays out a green (very green), data-driven plan to capture much of our atmosphere’s carbon pool.

Normally, the landscape in this photo would be a white ice sheet.

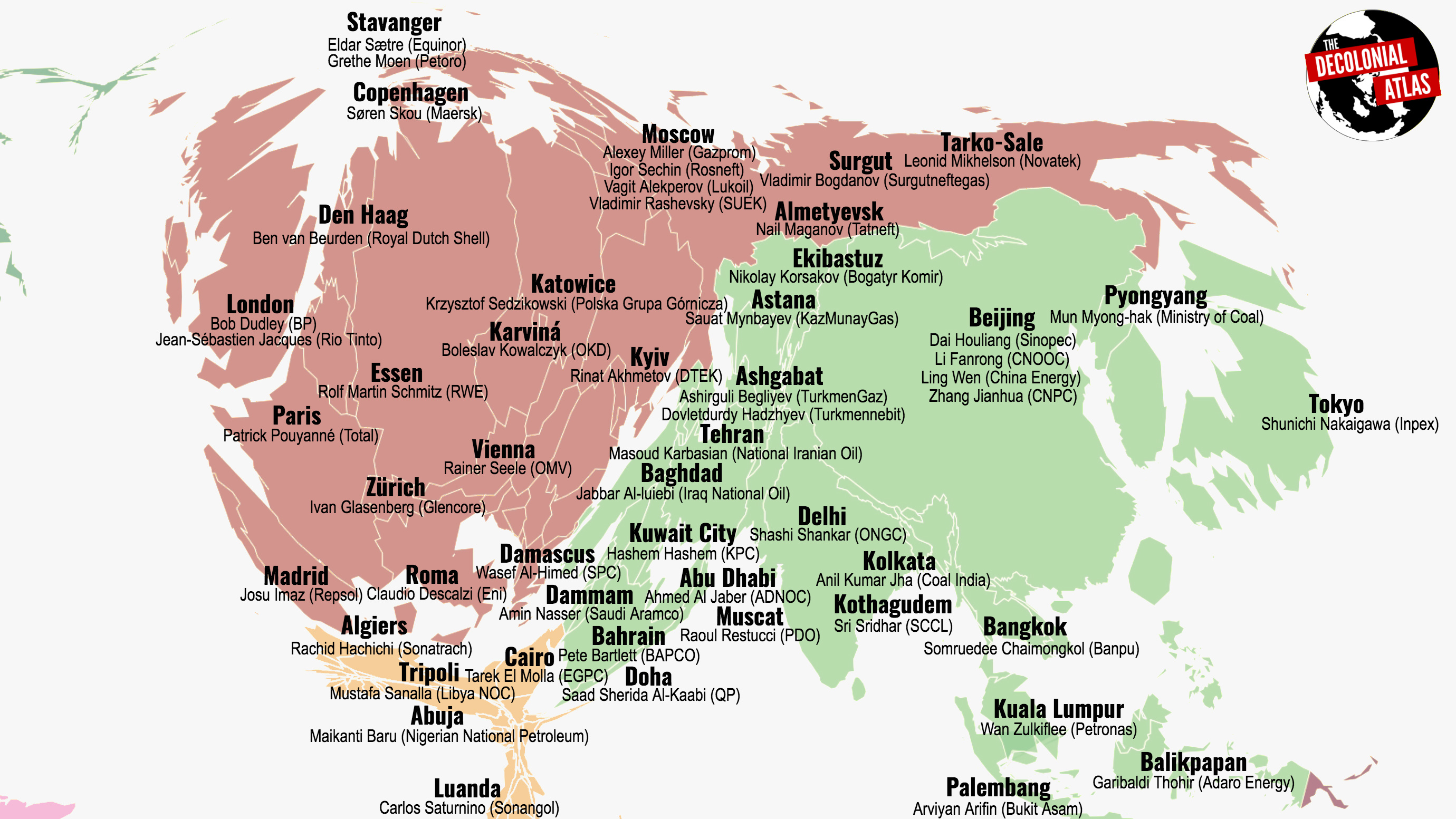

Controversial map names CEOs of 100 companies producing 71 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

At high tide each night, bright lights predict the underwater future.

New statistical analyses show that human-driven climate change is a virtual certainty.

Despite tens of millions of dollars pouring into new technologies, a ‘clean’ burger remains elusive.

Between the noise and frustration, we’re suffering more than ever.

A trio of scientists from Harvard hopes to do this in 2019.

Thanks to museum curators, there’s no shortage of the stuff.

The climate change we’re witnessing is more dramatic than we might think.

A new paper in Nature adds urgency to the fight against climate change.

The modern ocean can be a dangerous place for whales.

Evolution exists and exerts itself in a different way than gravity does… because natural selection is an “algorithmic force.”