society

In terms of sheer productivity, “-gate” has no peer. Wikipedia’s list of -gates has over 260 entries.

Reality is more distorted than we think.

▸

with

For the ancients, hospitality was an inviolable law enforced by gods and priests and anyone else with the power to make you pay dearly for mistreating a stranger.

Research shows that those who spend more time speaking tend to emerge as the leaders of groups, regardless of their intelligence.

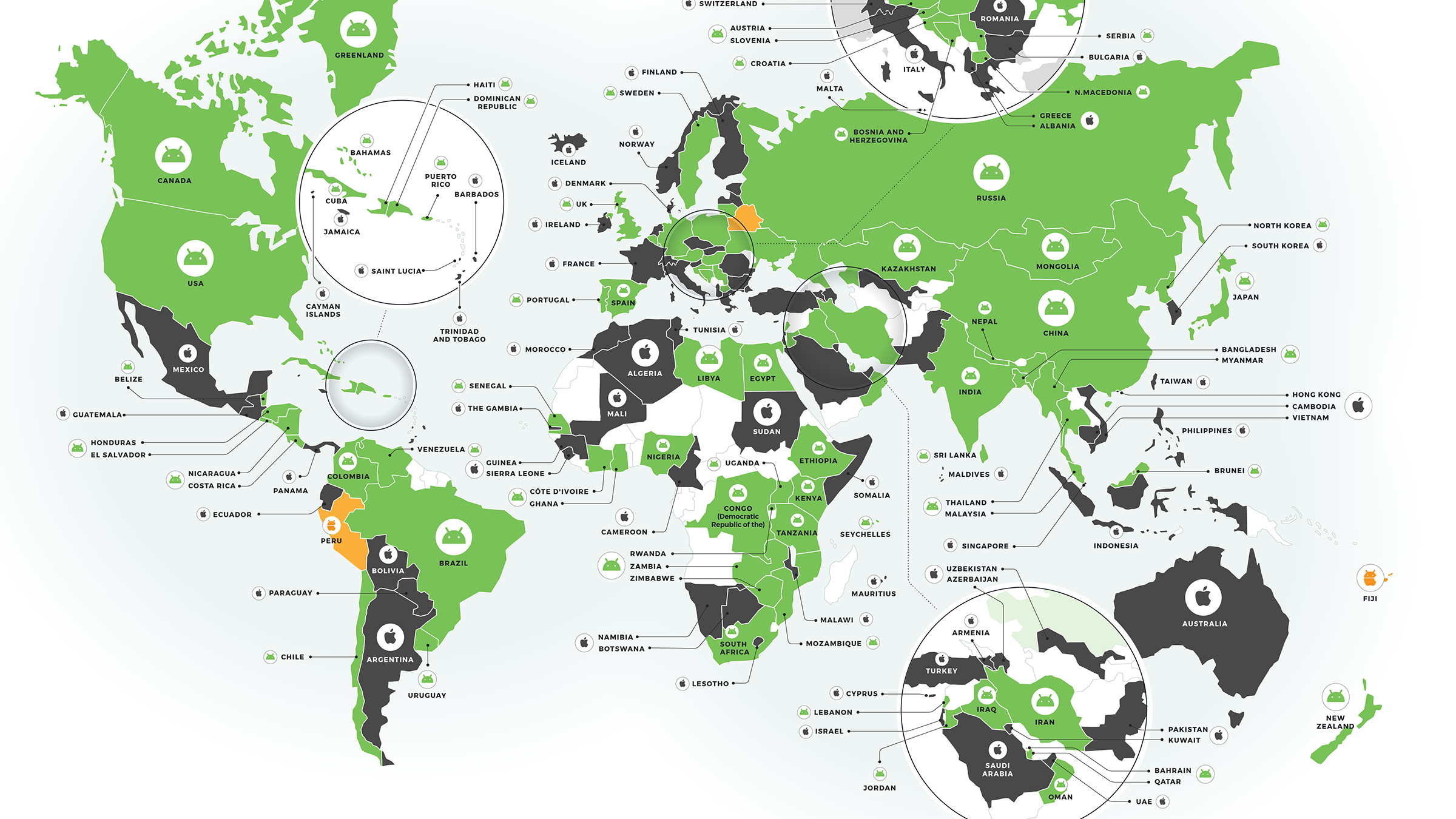

A global survey shows the majority of countries favor Android over iPhone.

Some of these trends may be due, in part, to the lockdown.

For decades, researchers have proposed that climate change and human-caused environmental destruction led to demographic collapse on Easter Island. That’s probably false, according to new research.

Technology usually has more pros than cons, but every benefit still carries some risk.

He’s studied apes for 50 years – here’s what most people get wrong.

▸

6 min

—

with

The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis argues that a comet strike caused major changes to climate and human cultures on Earth about 13,000 years ago.

ExtendNY stretches the Big Apple’s gridiron all across the globe – with some bizarre effects

Some wild animals thrive near humans, but only up to a point.

Humans may have evolved to be tribalistic. Is that a bad thing?

▸

17 min

—

with

Many people believe that in the face of profound evil, they would have the courage to speak up. It might be harder than we think.

Why are rapture ideologies exploding?

▸

7 min

—

with

A Harvard professor’s study discovers the worst year to be alive.

Instead of insisting that we remain “free from” government control, we should view taking vaccines and wearing masks as a “freedom to” be a moral citizen who protects the lives of others.

Escaping the marshmallow brain trap.

▸

6 min

—

with

Hunter-gatherers probably had more spare time than you.

“It’s not always about agreement, more often it’s about business.”

The retraction crisis has morphed into a citation crisis.

The public sphere should be open to conflict.

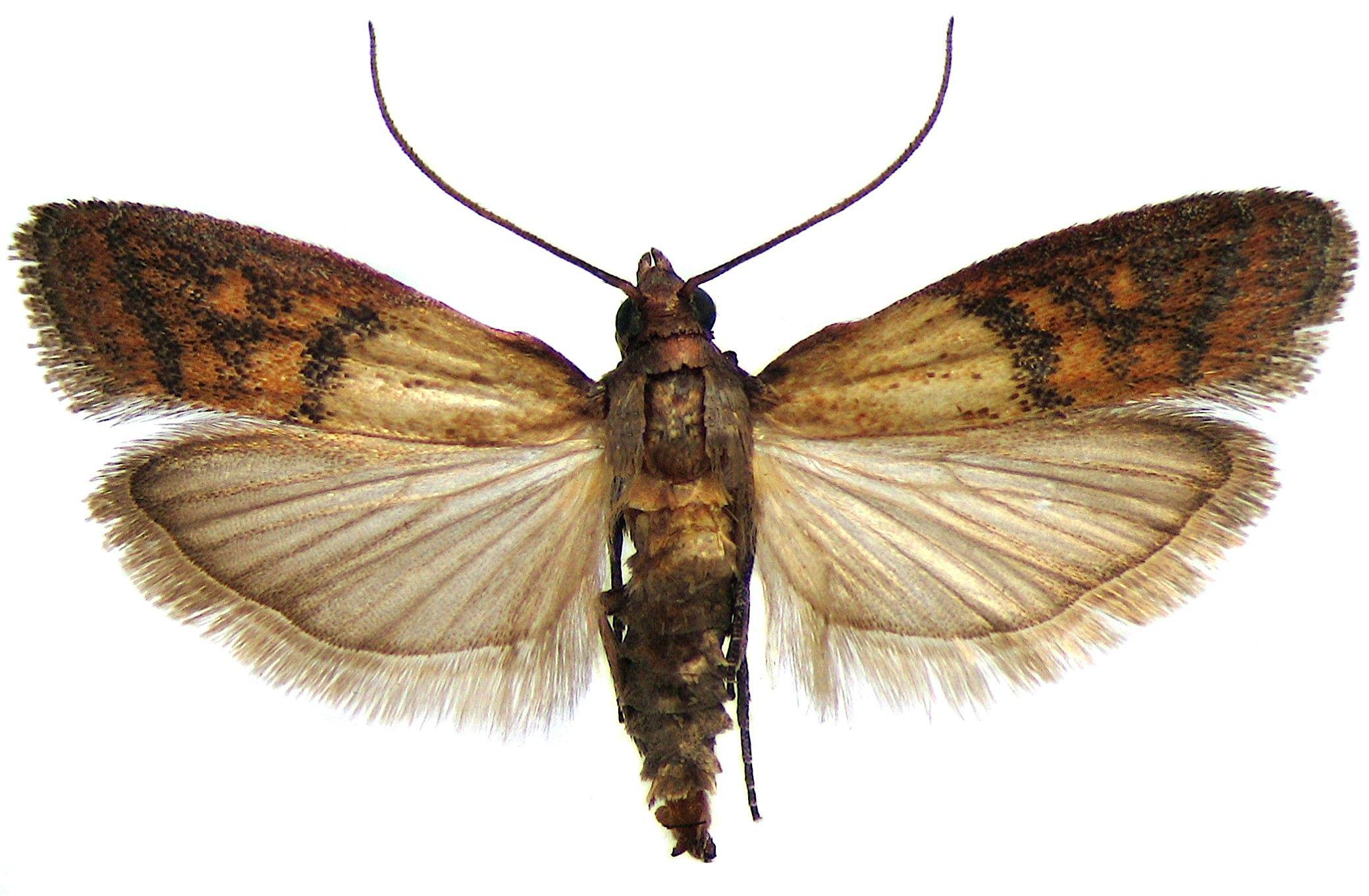

Biologists use commonly-found insects that engage in cannibalism to prove a key evolutionary concept.

The ‘reasonable person’ represents someone who is both common and good.

How the German political philosopher called out Henry David Thoreau on civil disobedience.

The independent news collective is teaching a new generation of journalists and citizens to spot the stories in plain sight.

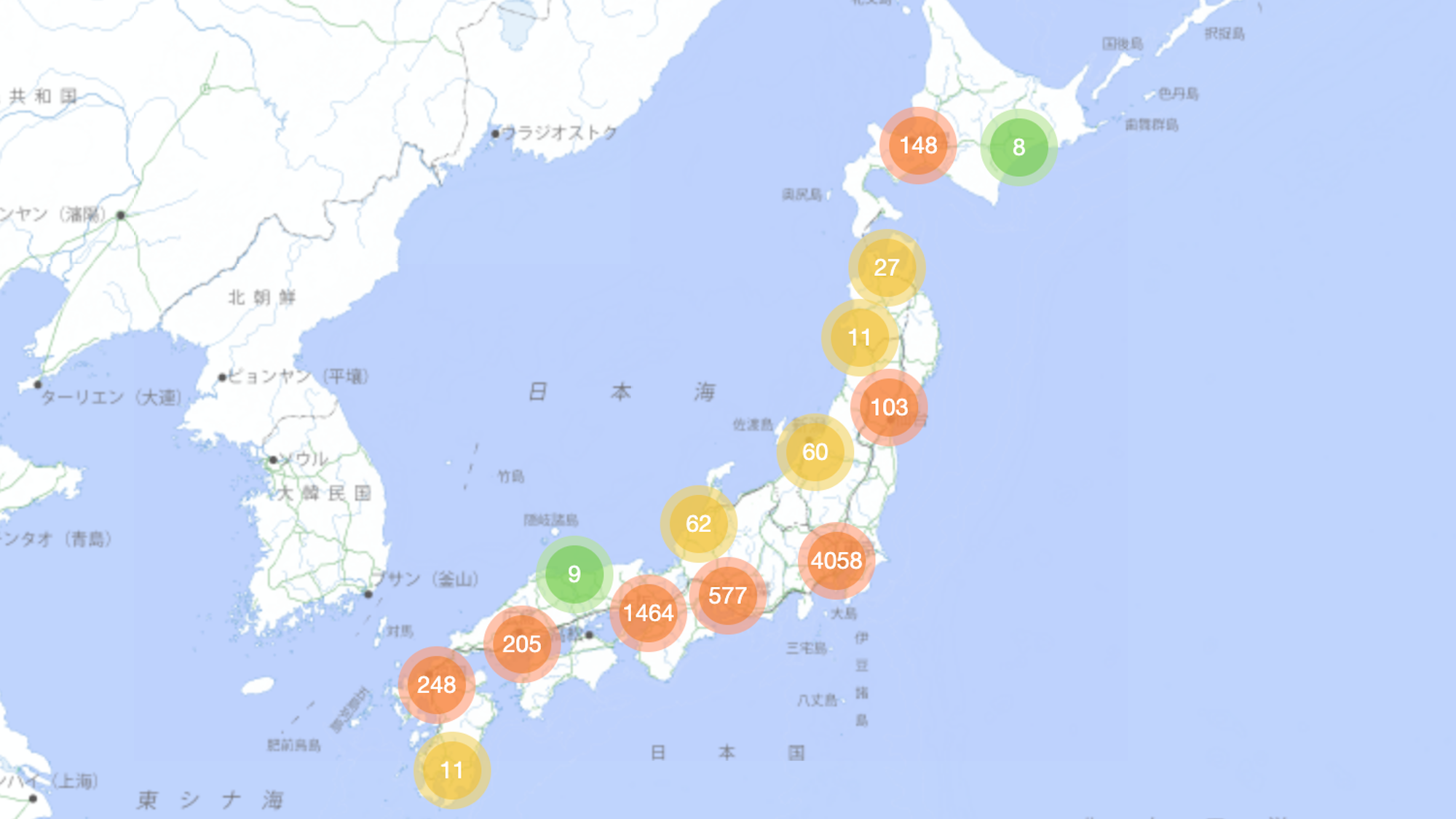

‘Dorozoku’ map crowd-sources the whereabouts of noisy kids in Japan – but who’s being anti-social here, exactly?

If we lose our pollinators, we’ll soon lose everything else.

Most people seem to enjoy liberalism and its spin offs, but what is it exactly? Where did the idea come from?

And if they could, would they care, asks philosopher John Gray in his new book.