public spaces

The public sphere should be open to conflict.

How the German political philosopher called out Henry David Thoreau on civil disobedience.

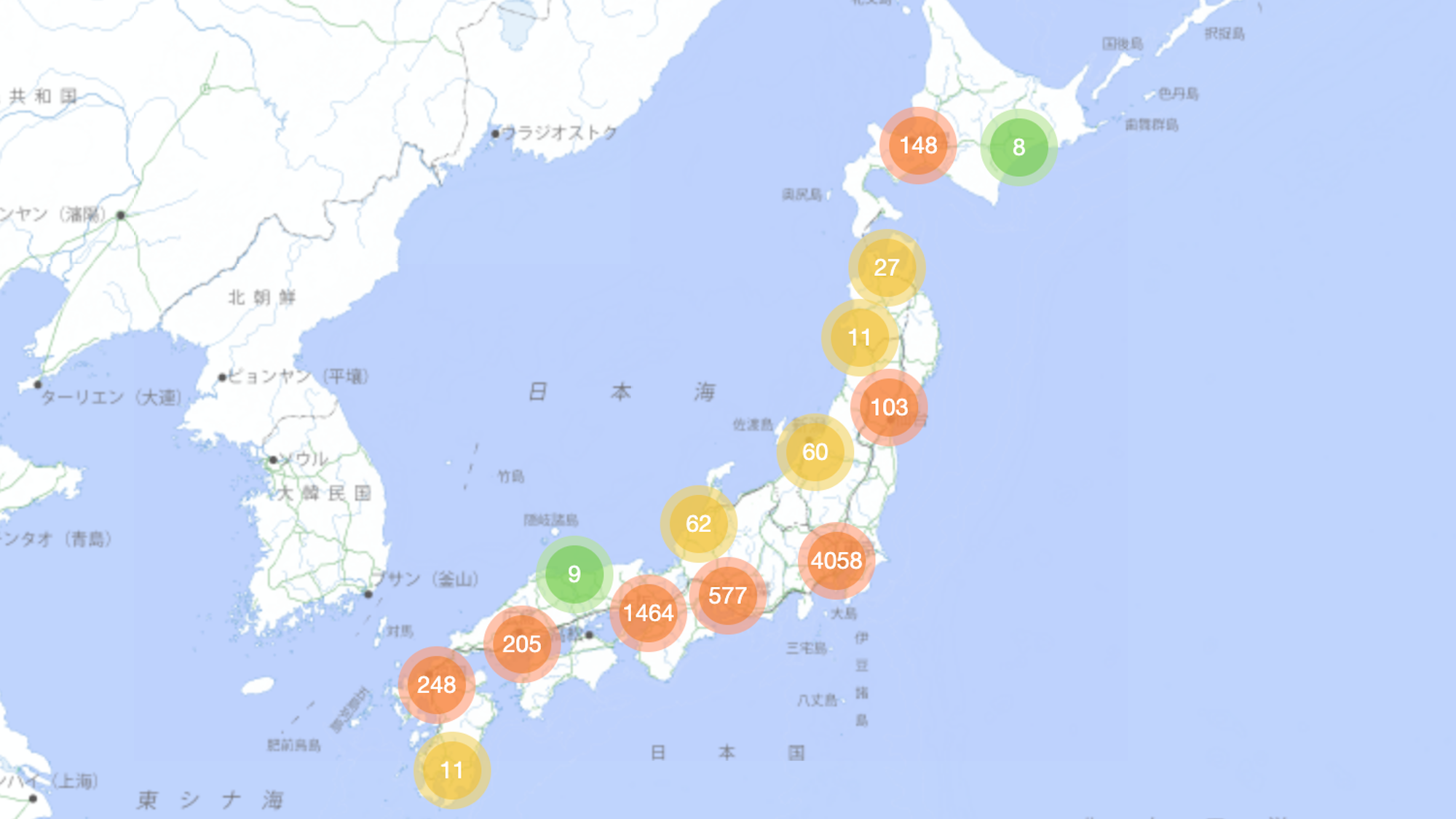

‘Dorozoku’ map crowd-sources the whereabouts of noisy kids in Japan – but who’s being anti-social here, exactly?

User-driven sites lead to user-based bias.

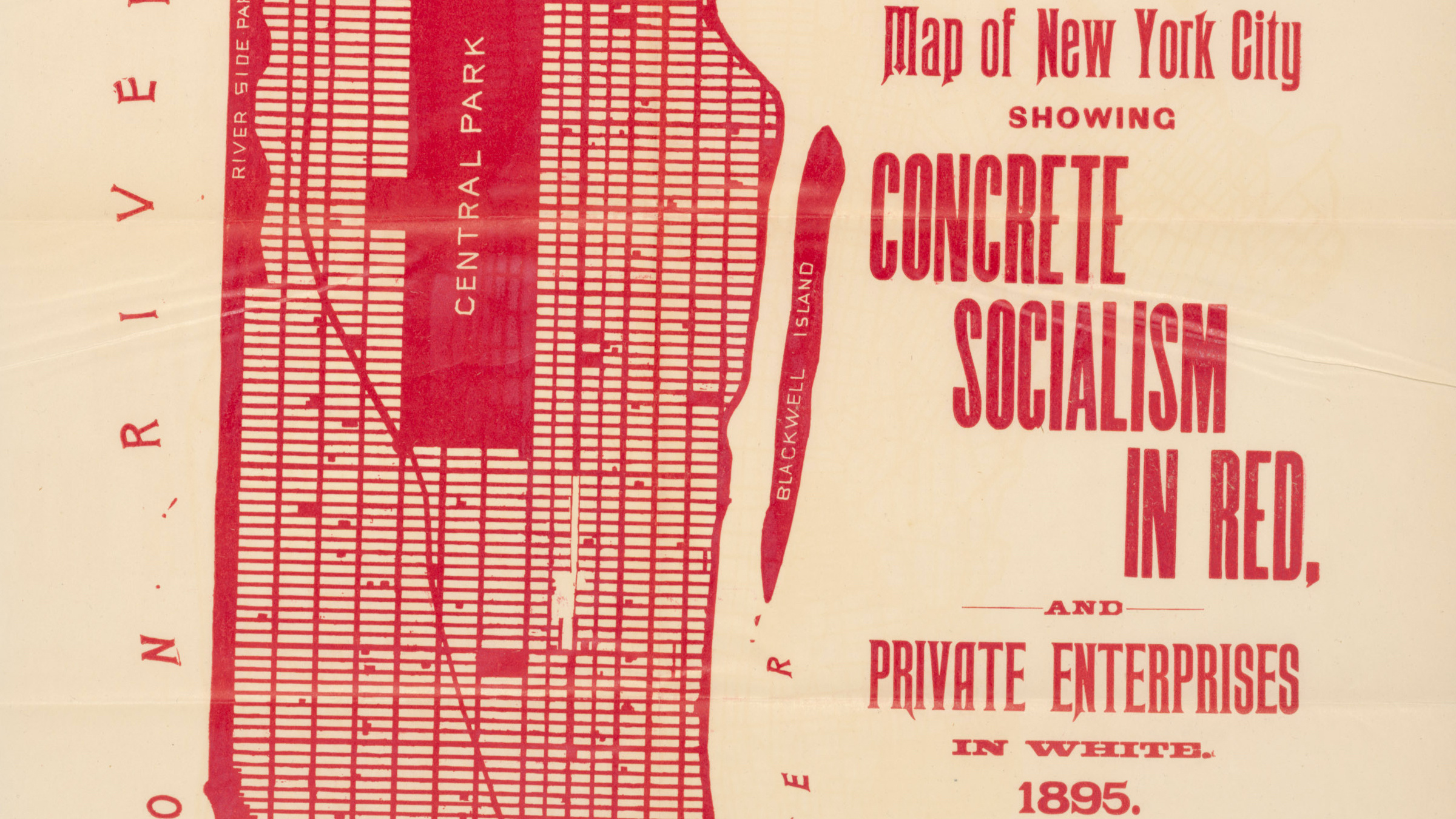

1895 map of New York City shows ‘concrete socialism’ in red, ‘private enterprises’ in white.

The word “learning” opens up space for more people, places, and ideas.

▸

3 min

—

with

Comfort has won, and most formality is gone.

Sometimes the best way to make changes is when you’re in the middle of a challenging time.

Hospitals are running out of critical face masks as civilians are panic-buying medical supplies en masse amidst the coronavirus global pandemic.

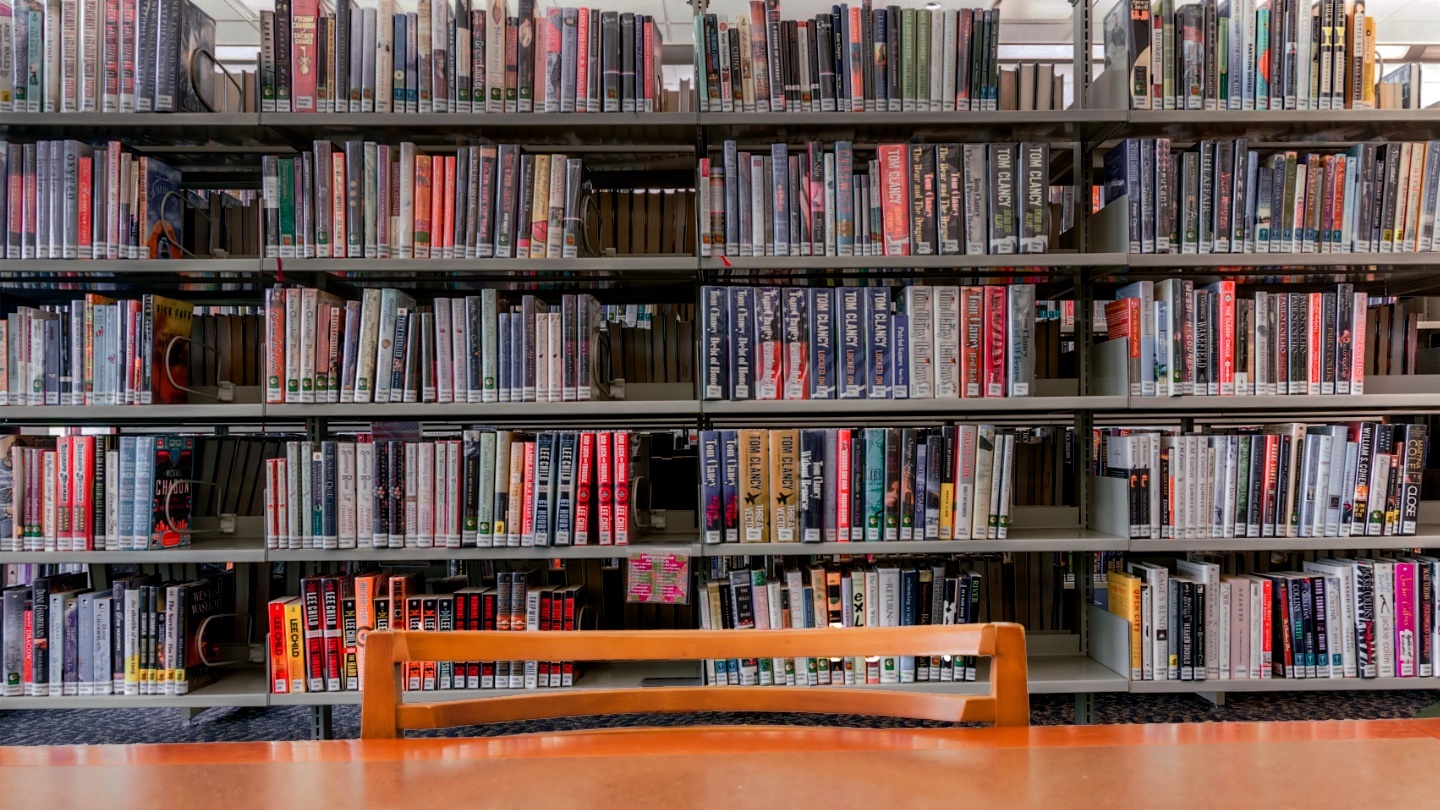

With the realization that overdue charges disproportionately affect access for low-income readers, libraries are reconsidering the value of fees.

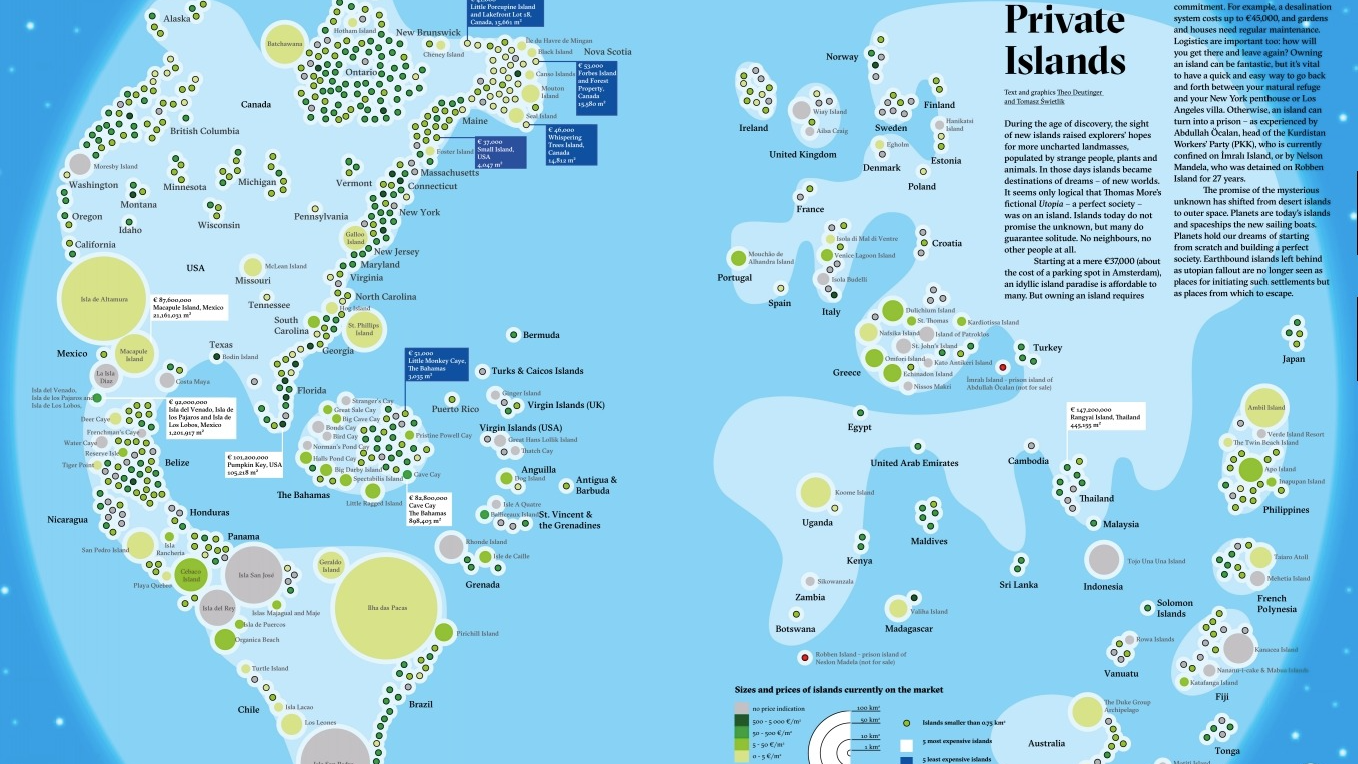

There’s something special about islands – in some cases, it’s the price tag

Fauna and flora refuse to go quietly into the Anthropocene.

Combined with high-capacity public transport, AVs could remove 9 out of every 10 cars in a mid-sized European city.

Ideas are plentiful; execution is another story.

In any sufficiently large protest, police officers may “kettle” protesters. Critics say it violates human rights, while advocates claim its one of the few safe tools available to police during a protest.

Hearing-related problems are on the rise.

Unfortunately, this means that drivers act more aggressively on the road when spotting cyclists.

As we urbanize, a new study flags the need for lots of green spaces.

U.S. laws regulating online speech offer broad protections for private companies, but experts worry free expression may be threatened by “better safe than sorry” voluntary censorship.

It may create the conditions for further inequality.

You can become a tree or even the soil supporting it.

Luxembourg will offer the world’s first fare-free public transit system, but is there really such a thing as a free ride?

Thousands of churches are left behind every year in America.

New research links urban planning and political polarization.

All the prayers in the world to the Flying Spaghetti Monster probably won’t help.

Now is a good time to brush up on who’s on the ballot.

It’s not so rare as many think.