prison

What’s the difference between brainwashing and rehabilitation?

A new study suggests that private prisons hold prisoners for a longer period of time, wasting the cost savings that private prisons are supposed to provide over public ones.

The US prison system continues to fail, so why does it still exist?

▸

18 min

—

with

‘Critical Tourist Map of Oslo’ offers uniquely dark perspective on Norway’s capital.

The Labour Economics study suggests two potential reasons for the increase: corruption and increased capacity.

What makes some psychopaths better able to control their antisocial tendencies?

Over 800 prisoners in Texas relate their experiences.

Can AI make better predictions about future crimes?

Scholars often debate risking their livelihoods and personal safety in order to conduct research in certain areas.

“People are not commodities!” said Assemblyman Rob Bonta.

Until the use of prison labor is banned, many stakeholders will be incentivized to prevent felons from being rehabilitated.

Researchers discover government agencies use facial recognition software on photos from local DMVs.

Activist and Big Think reader Roy M. Arce explains his idea for a new community policing team and how it can halt vicious cycles of PTSD and homelessness.

Here’s how we can use the concept of “impact impression” for criminal reform.

▸

5 min

—

with

What happens to a person’s identity when they are forced to play a hypermasculine role just to survive?

The U.S. has a talent shortage and the formerly incarcerated have paid their debt to society. Let’s solve two problems with one idea.

▸

5 min

—

with

The formula for resilience? Hope, grit, and amnesia.

▸

4 min

—

with

One flew east, one flew west, eight shrinks flew into the cuckoo’s nest.

Climate change is a dire threat, perhaps it is time to put the people who created and denied the problem on trial?

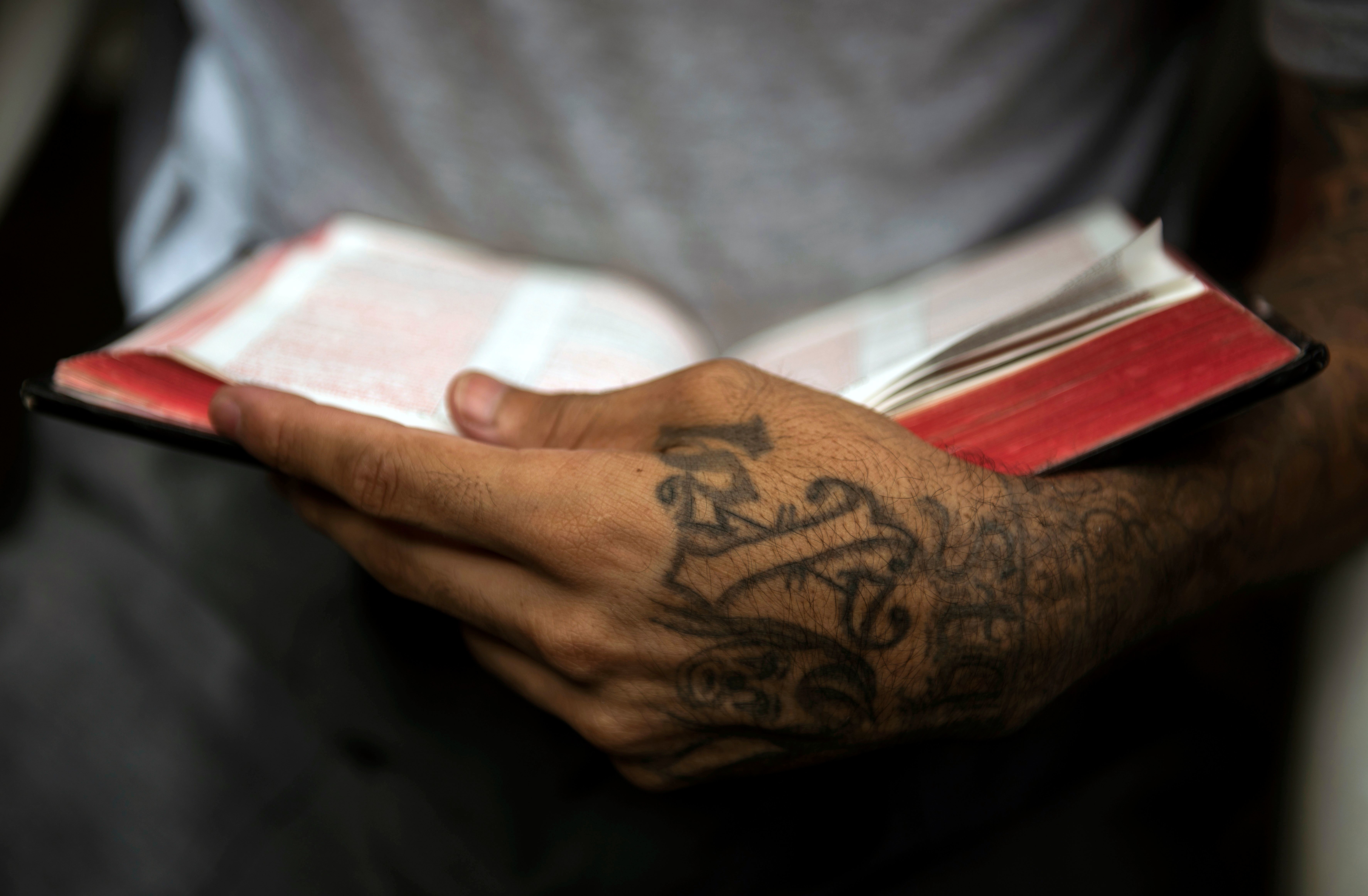

For Damien Echols, tattoos are part of his existential armor.

▸

5 min

—

with

The history of the Geneva Conventions tells us how the international community draws the line on brutality.

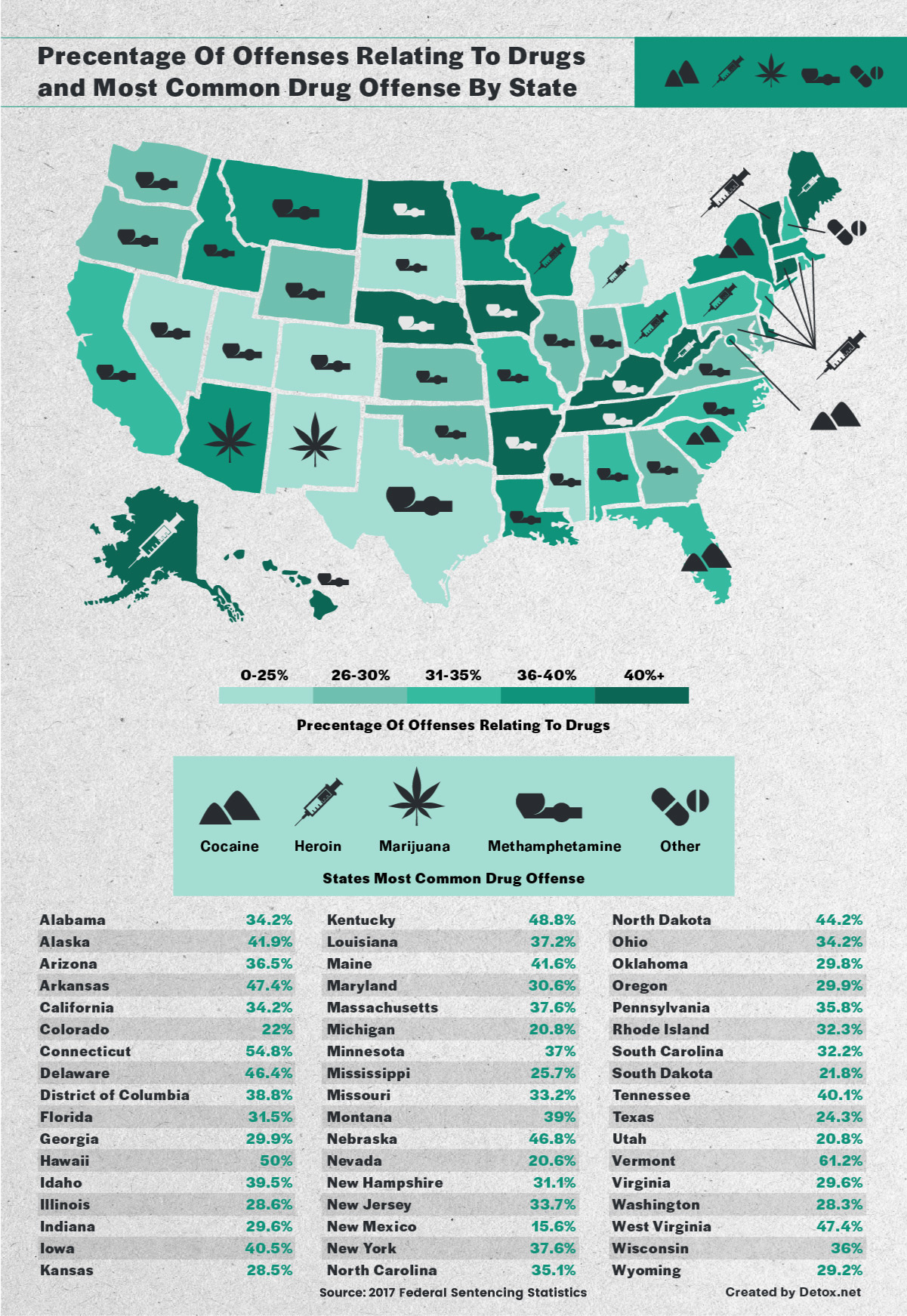

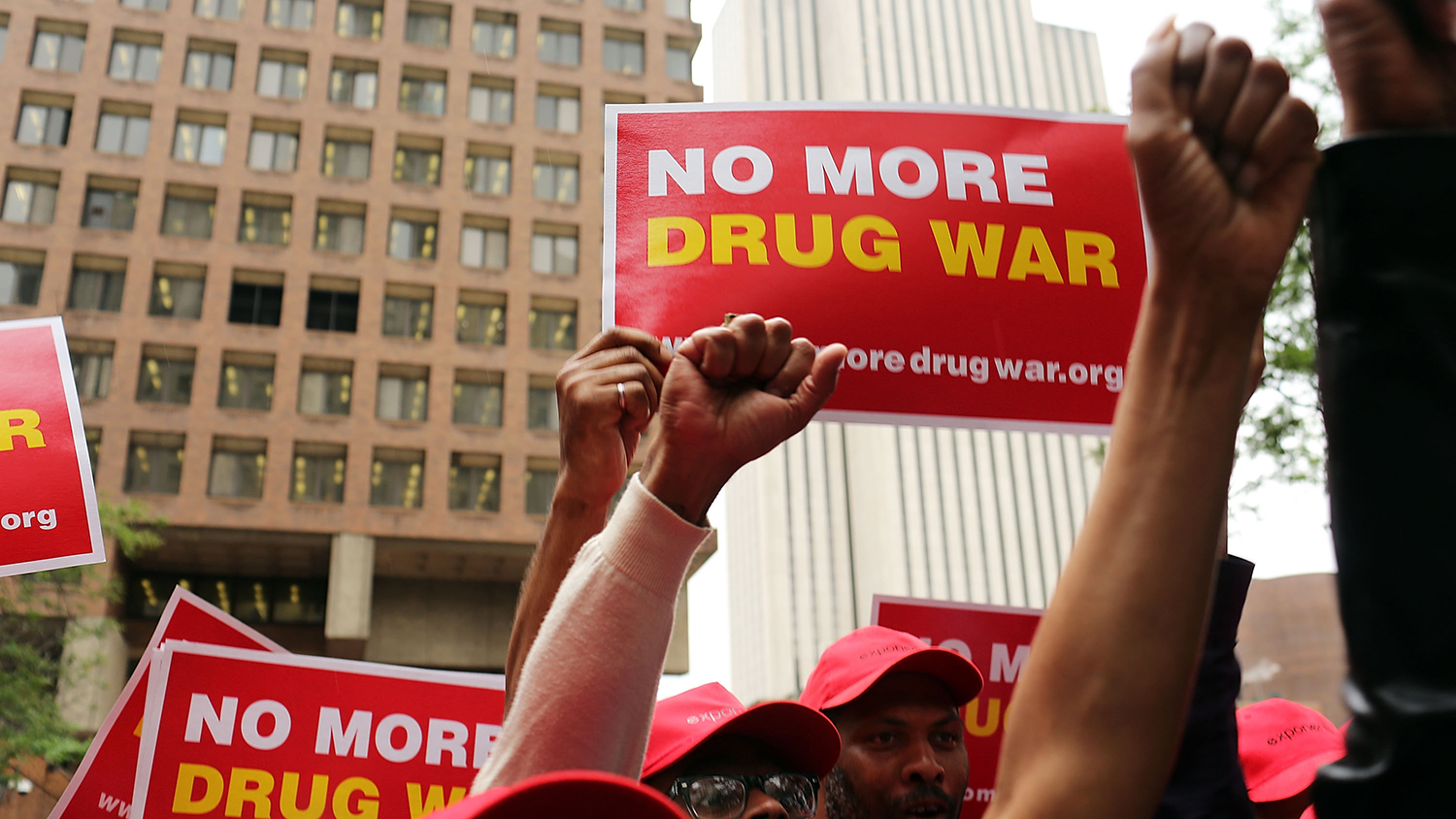

Drug use and arrests are rising overall, but those changes vary depending on the state.

Bishop Jahwar saw first-hand that prison often doesn’t work as intended.

▸

4 min

—

with

A new report outlines how the CIA considered using a drug called Versed on detainees in the years following 9/11.

How to stay present and stop your mind from fixating.

▸

8 min

—

with

Unlikely allies can solve society’s most complex problems.

▸

7 min

—

with

Meditation with a mystical edge? Don’t knock magick ’til you’ve tried it.

▸

12 min

—

with

Kayne West’s tweet that the United States should amend the 13th Amendment brought renewed attention to a flaw in its language.

Norway’s decision to push drug felons through treatment is a huge step forward.

The Brazilian government has been trying to answer this very question in its ever-growing prison population, which has doubled since the year 2000.