identity

A study reports that people think those with similar personality traits look alike and vice versa.

Reality is more distorted than we think.

▸

with

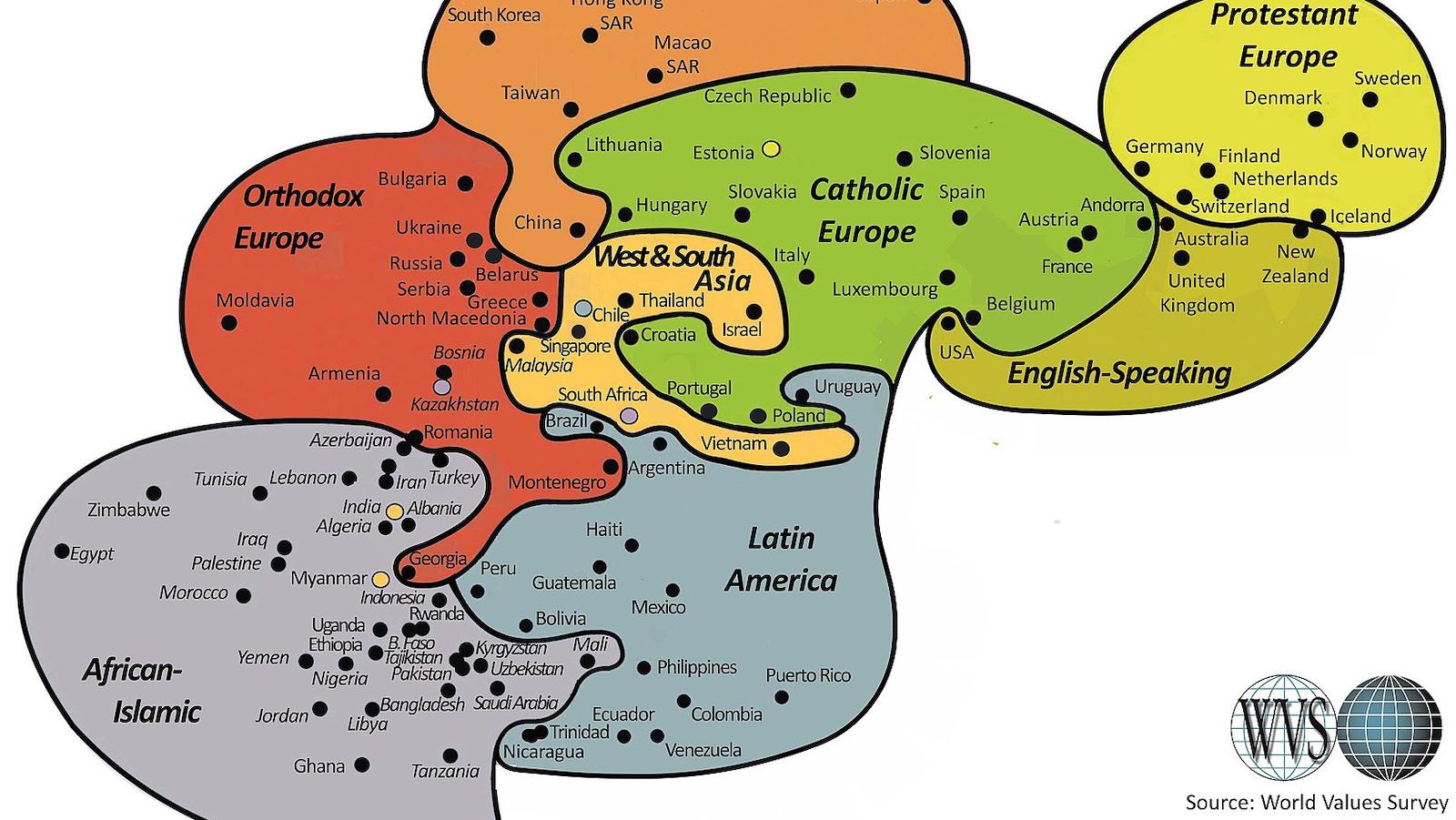

The Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural map replaces geographic accuracy with closeness in terms of values.

Humans may have evolved to be tribalistic. Is that a bad thing?

▸

17 min

—

with

Why are rapture ideologies exploding?

▸

7 min

—

with

How fabric helped build modern civilization.

▸

6 min

—

with

The more you see them, the better you get at spotting the signs.

Scans show similar activity to what occurs when you think about yourself.

Remedies must honor the complex social dynamics of adolescence.

What can ‘behaviorism’ teach us about ourselves?

The study found that people who spoke the same language tended to be more closely related despite living far apart.

Answering the question of who you are is not an easy task. Let’s unpack what culture, philosophy, and neuroscience have to say.

▸

12 min

—

with

As morally sturdy as we may feel, it turns out that humans are natural hypocrites when it comes to passing moral judgment.

▸

5 min

—

with

A new study found that personality growth in young adults predicted career benefits such as income, degree attainment, and job satisfaction.

The color of toys has a much deeper effect on children than some parents may realize.

▸

6 min

—

with

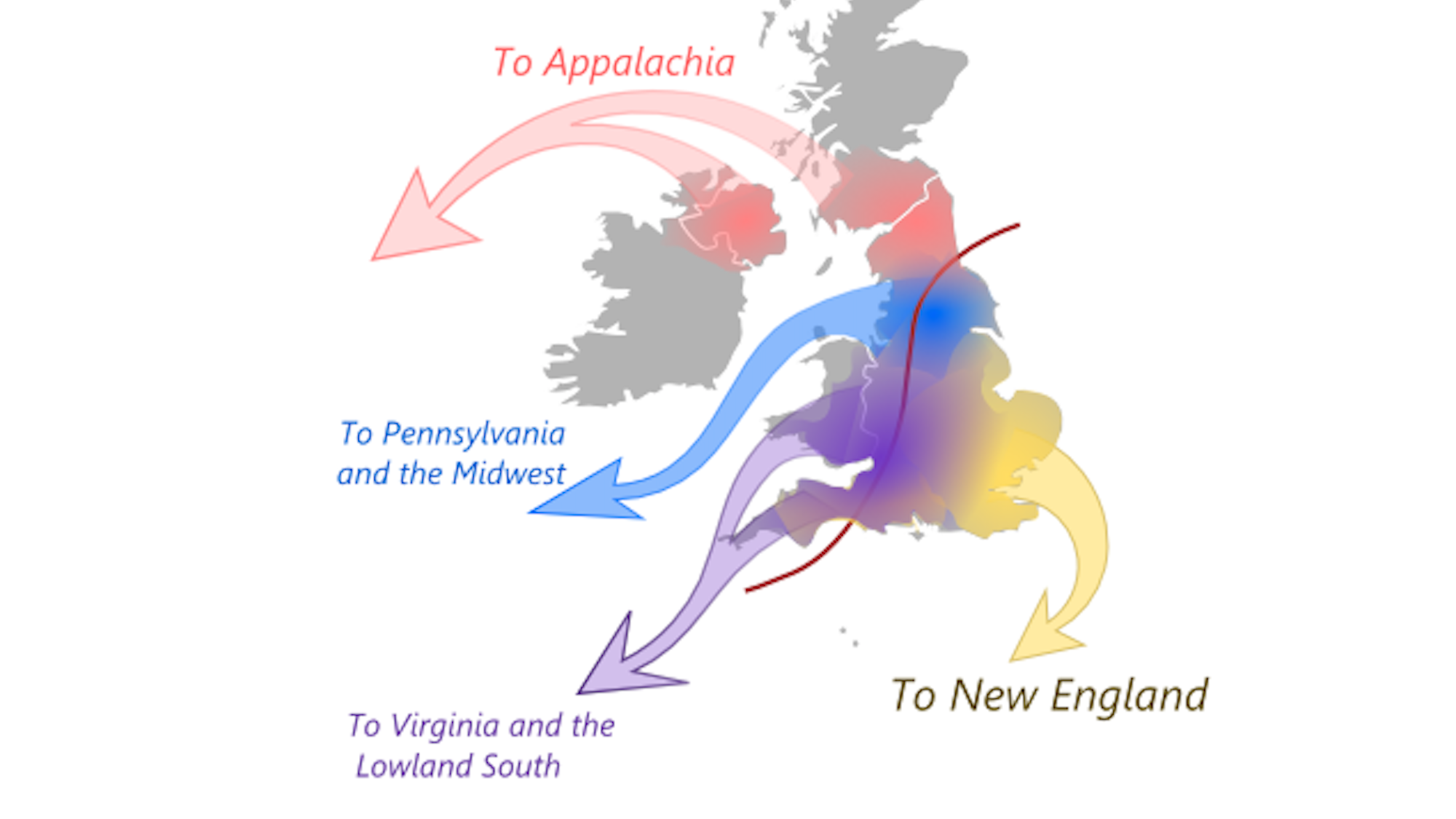

They came from different places and with different ideas, which still resonate today.

Thought expriments are great tools, but do they always do what we want them to?

There are pros and cons to owning a pet as a marginalized individual.

The English Department is instituting a series of reforms that cuts across the entire university.

Can thinking about the past really help us create a better present and future?

Are we genetically inclined for superstition or just fearful of the truth?

▸

13 min

—

with

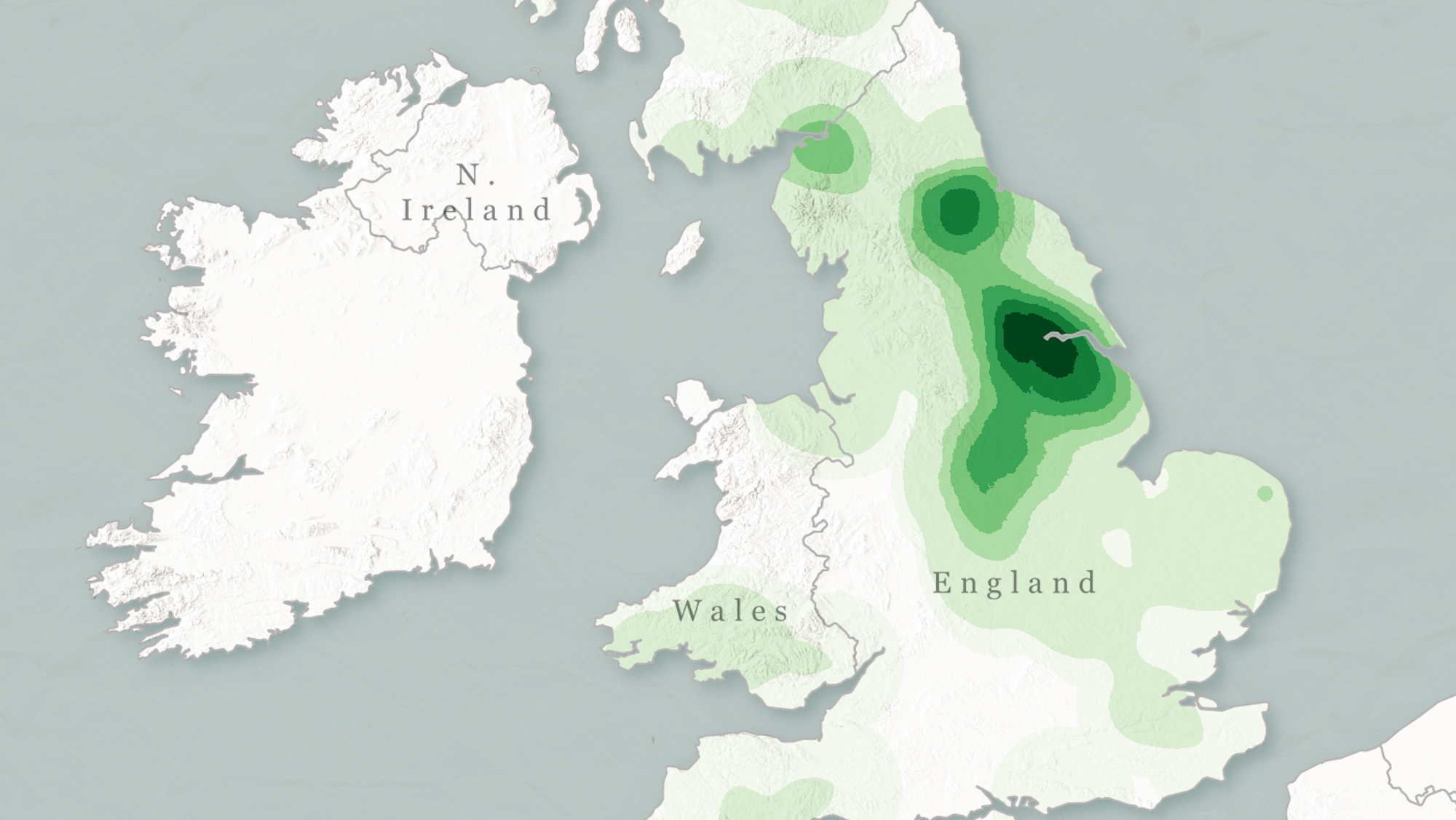

Mapping the frequency of common toponyms opens window on Britain’s ‘deep history’.

Exploring how a small change in your DNA sequence can make you a natural blonde.

Thanks to modern technology, we can reexamine our assumptions about ancient warriors.

Did you know that shifting to a positive perspective on aging can add 7.5 years to your life? Or that there is a provable U-curve of happiness that shows people get happier after age 50?

▸

01:02:06 min

—

with

The programming giant exits the space due to ethical concerns.

It takes a special person with a special set of skills to reach students on an emotional level.

▸

4 min

—

with

What’s the worst thing that could happen, and can you live with that?

▸

7 min

—

with

To get a sense of faraway places, these ‘atlases’ let the locals give you their perspective.

Online dating has evolved, but at what cost?