biodiversity

The Vertebrate Genomes Project may spell good news for the kakapo and the vaquita.

Seawater is raising salt levels in coastal woodlands along the entire Atlantic Coastal Plain, from Maine to Florida.

Roughly the size of a thumbnail, this newly discovered toadlet has some anatomical surprises.

The organisms were anchored to a boulder 900 meters beneath the ice, living a cold, dark existence miles away from the open ocean.

Participation in community science programs has skyrocketed during COVID-19 lockdowns.

First picture of worldwide bee distribution fills knowledge gaps and may help protect species.

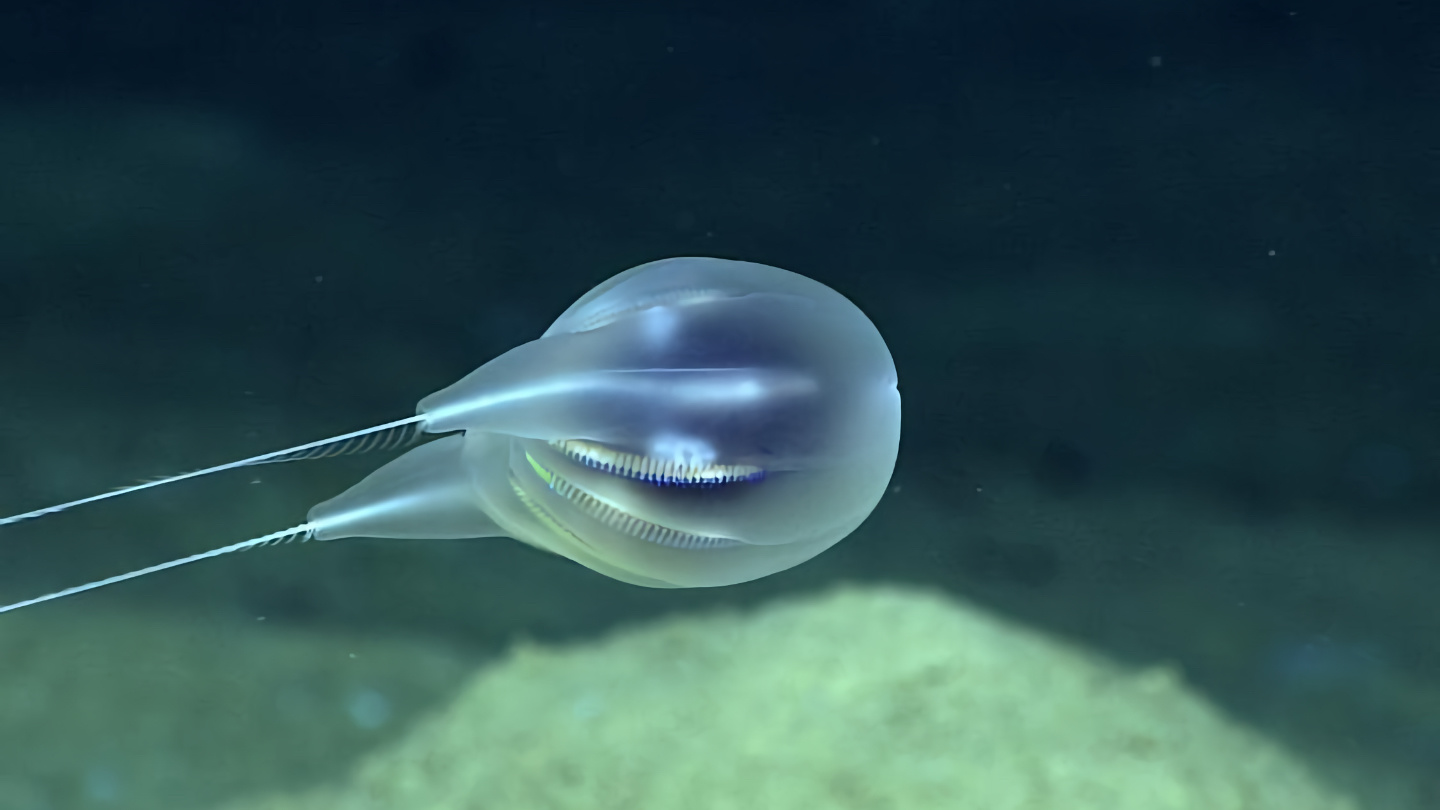

Exceptionally high-quality videos allow scientists to formally introduce a remarkable new comb jelly.

Researchers document the first example of evolutionary changes in a plant in response to humans.

Across the world, wildlife is under severe threat.

A study finds 1.8 billion trees and shrubs in the Sahara desert.

Creating a better understanding by clearing up common misconceptions about the neurodiversity movement.

An experiment in Botswana suggests a non-lethal deterrent for predatory lions.

Declining bee populations could lead to increased food insecurity and economic losses in the billions.

Scientists uncovered the secrets of what drove some of the world’s last remaining woolly mammoths to extinction.

The Sahara is a harsh environment today. It used to be much, much, worse.

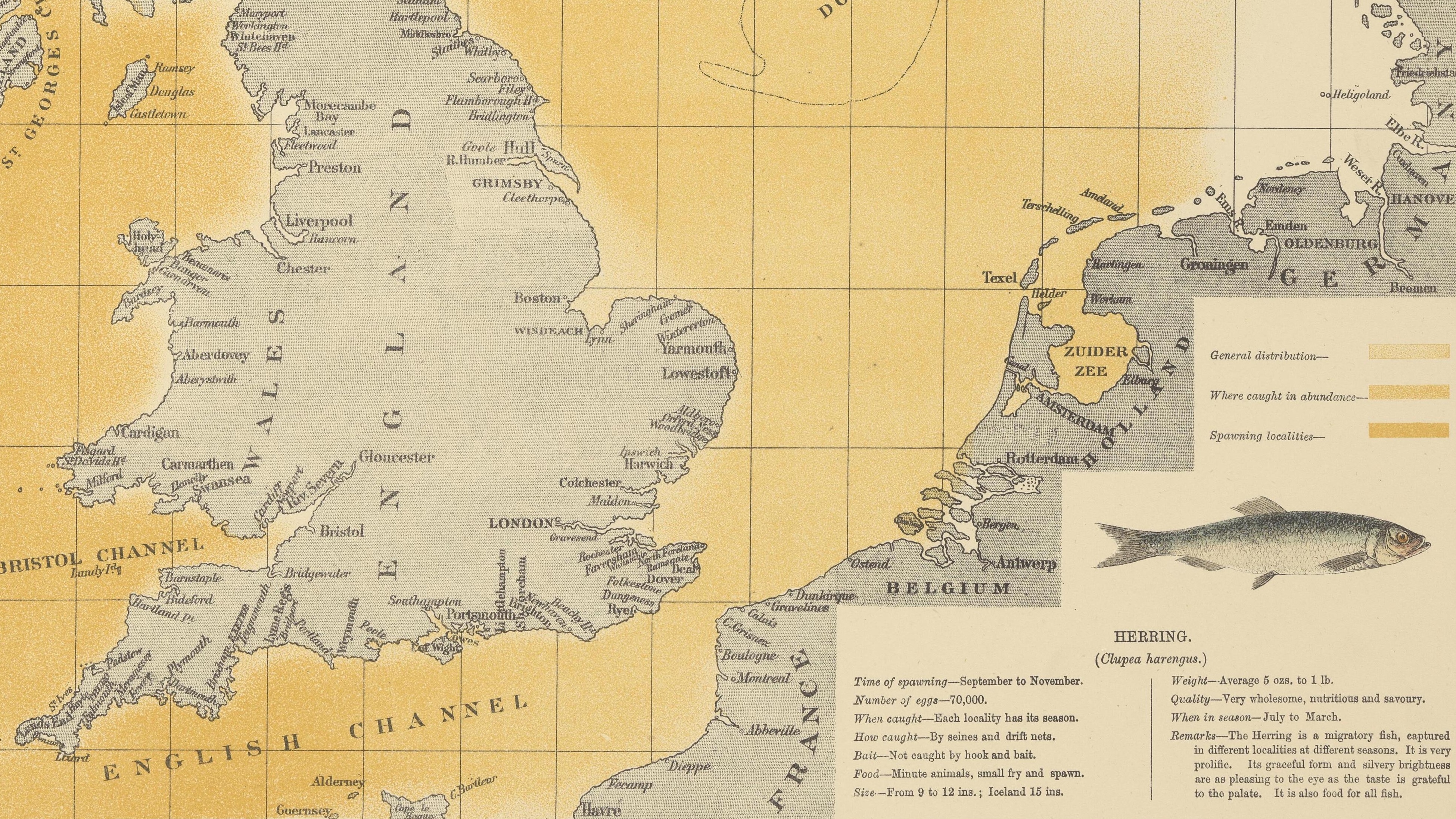

O.T. Olsen’s gorgeous ‘Piscatorial Atlas’ (1883) describes a world now destroyed and forgotten

Australia’s beloved and bizarre egg-laying mammal could start vanishing in coming years if current trends continue.

The relatively quick evolution of nine unusual shark species has scientists intrigued.

Hundreds more are documented in Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks.

Is the way we choose which animals to protect out of date?

Life forms on Earth are wildly varied, but scientists discover a single formula that predicts every one’s life cycle.

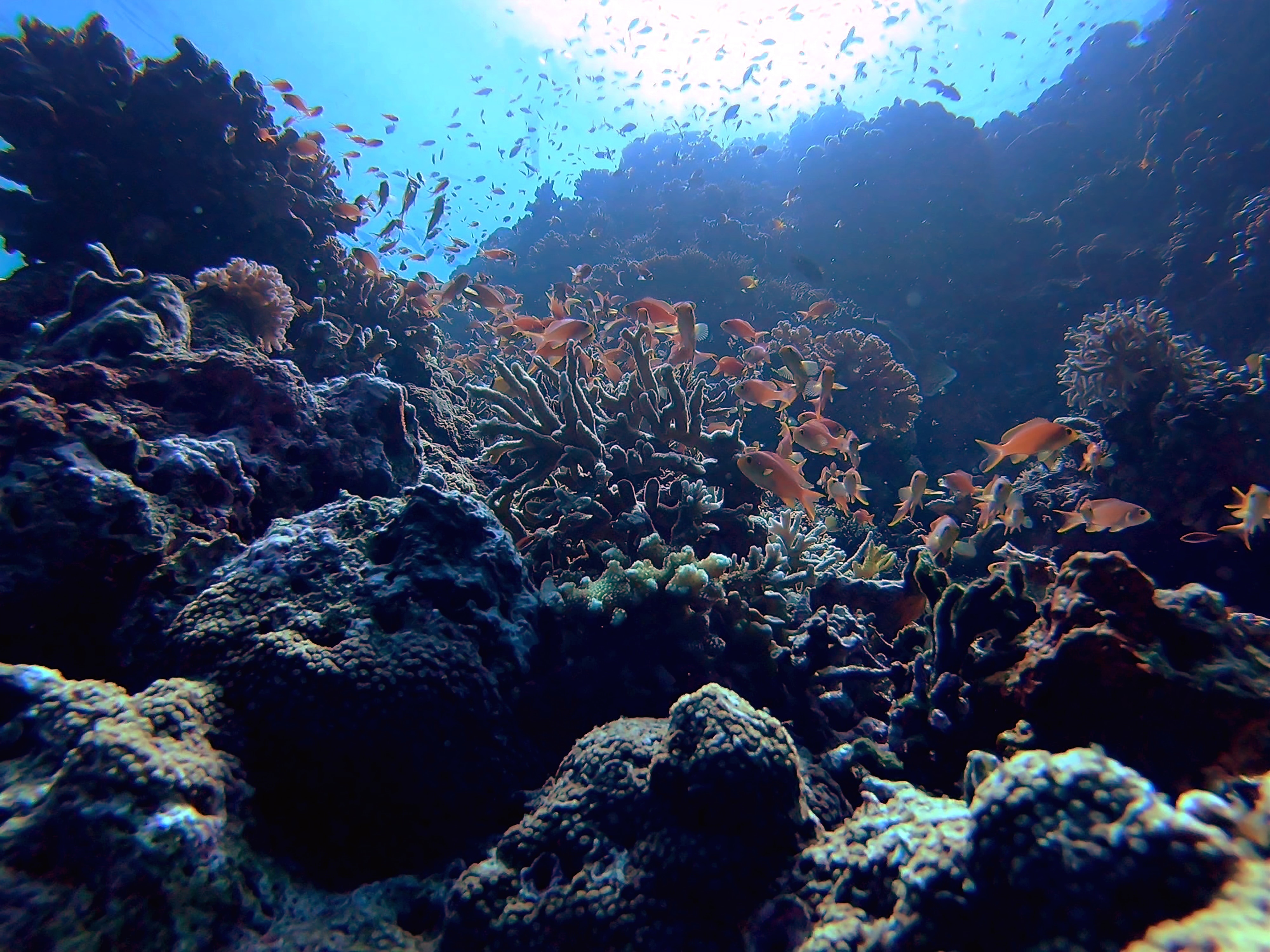

Let’s not kid ourselves: Coral reefs are in serious danger. But numerous ambitious projects are underway with the goal of keeping these ecosystems alive.

Two house mouse subspecies meet again in a hybrid zone strangely reminiscent of the Iron Curtain

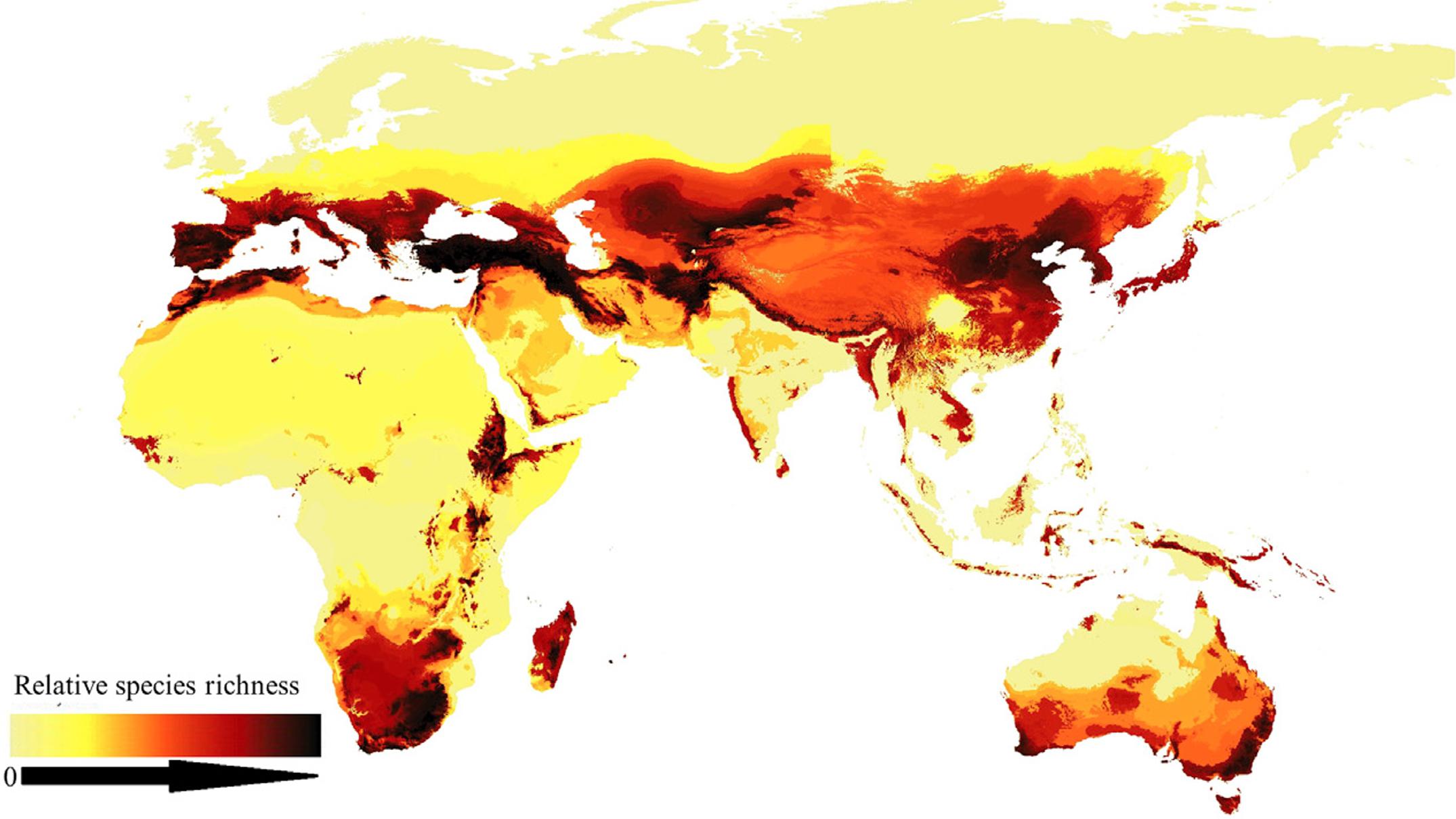

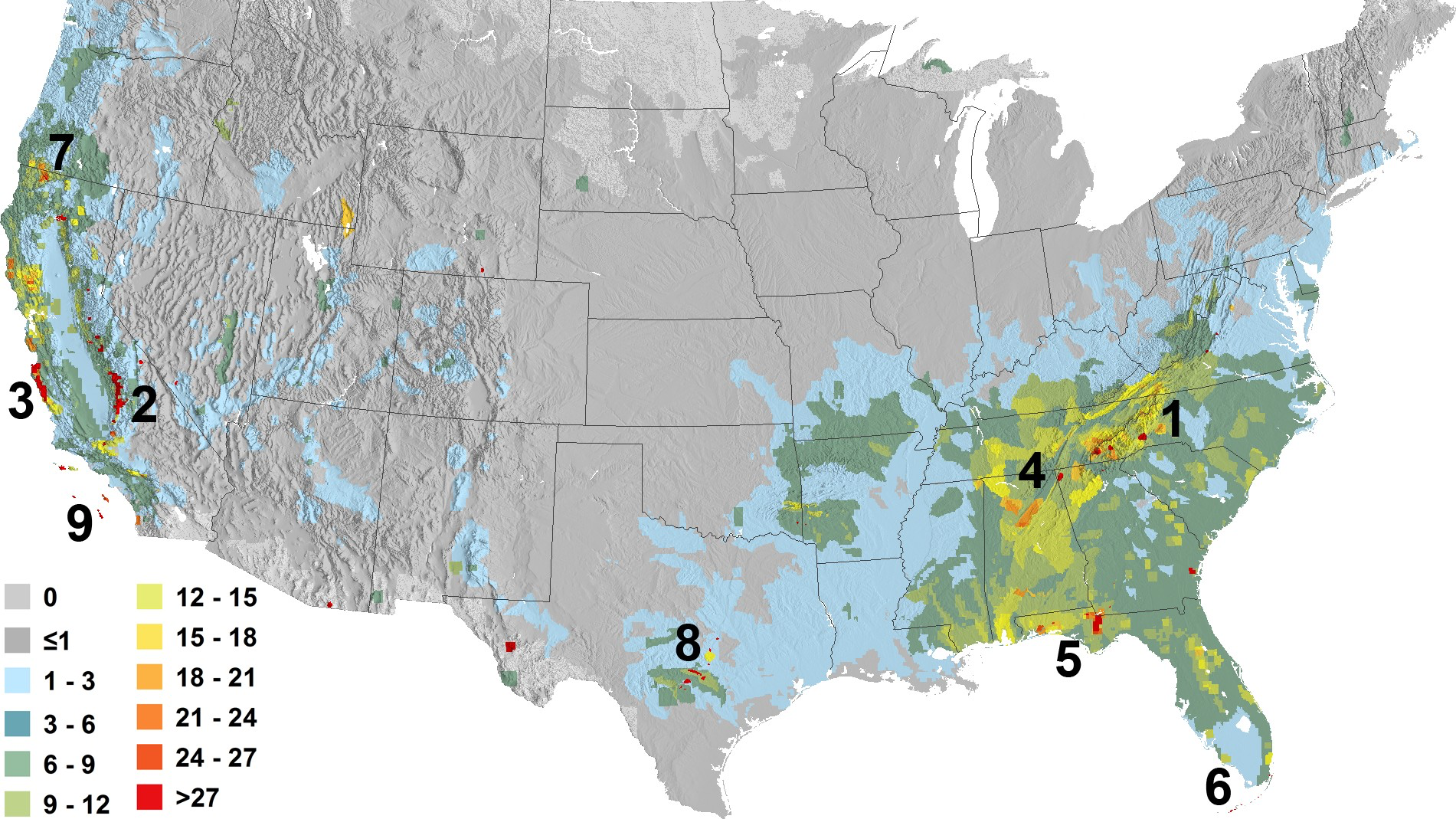

Project to map global ‘species richness’ highlights the variety of biodiversity itself

The blob that’s astonishing science gets its own exhibit.

While the blockbuster franchise might have given us a distorted view of science’s capabilities to address species extinction, new research might come close to “resurrecting” lost species’ DNA.

Octopuses are known to rapidly change colors during sleep, but it’s still unclear whether they dream like humans do.

The loss of elephants accelerates climate change.

Study finds that carbon dioxide emissions may trigger a reflex in the carbon cycle, with devastating consequences.