transportation

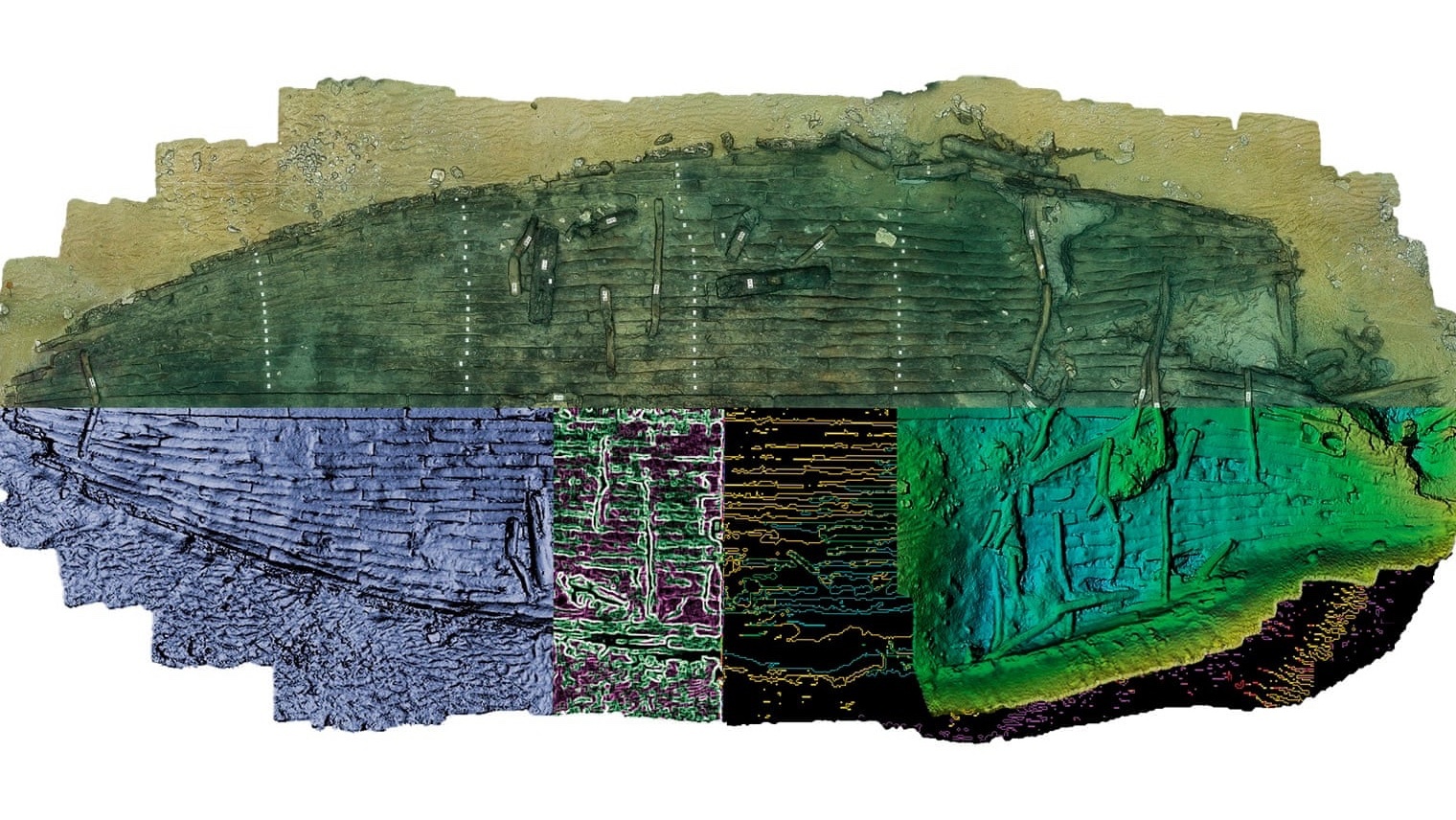

For centuries, the only way to travel between the Old and New World was through ships like the RMS Lusitania. Experiences varied wildly depending on your income.

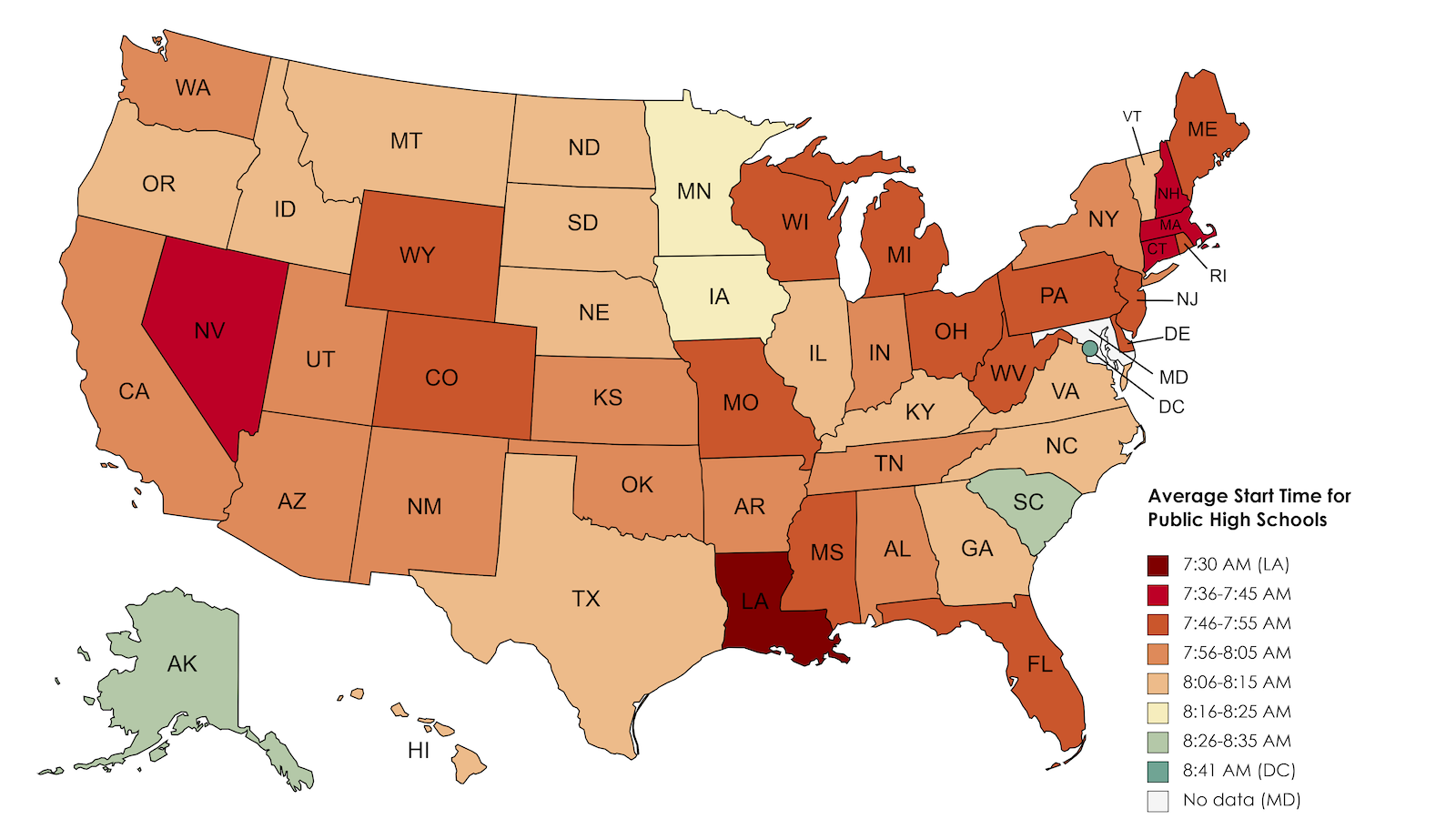

In Louisiana, high school starts at 7:30 am. Research shows that is at least an hour too early.

Americans don’t like to ride the bus. There are ways to fix that.

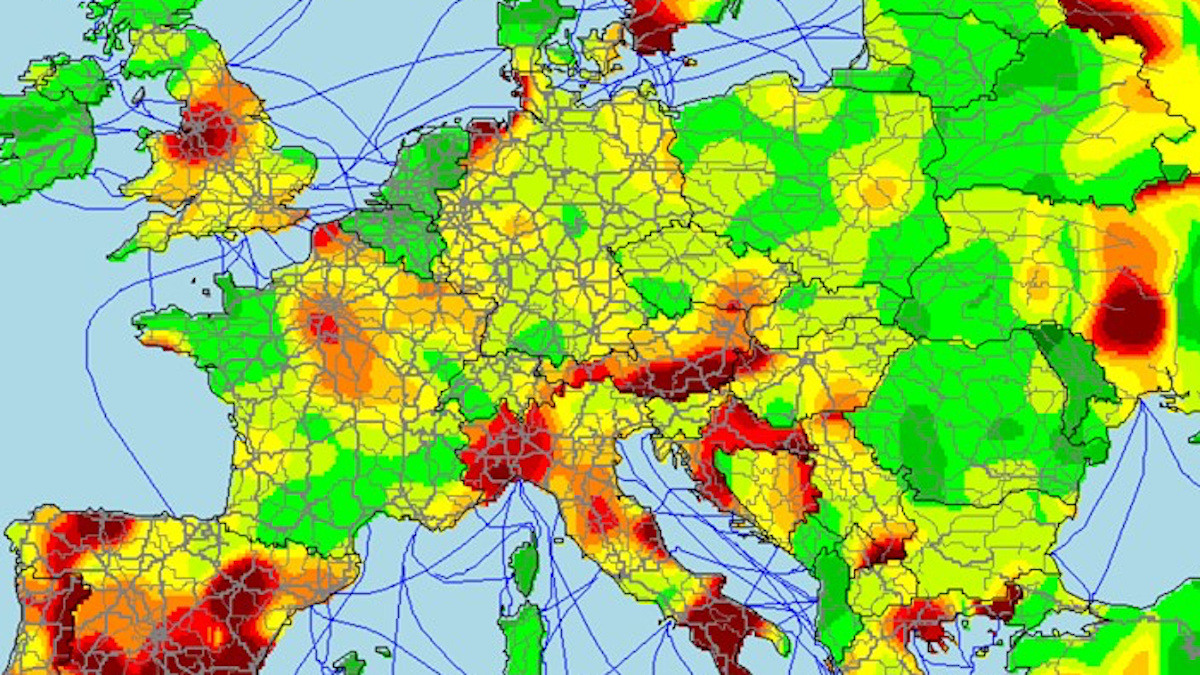

As air pollution increases, so does violent crime.

The Kazungula Bridge connects Zambia and Botswana, barely missing Namibia and Zimbabwe.

What’s to blame for the recent uptick in containership accidents?

Whose responsibility is it to ensure that there is affordable access to employment?

How many hurdles stand in the way of hyperloops becoming a commercial reality?

‘Kanal Istanbul’ would create a second Bosporus – and immortalize its creator.

We will travel again, but it will not be the same.

Do space and time really exist? NASA astronomer Michelle Thaller looks at the implications of Einstein’s famous equation E=mc2.

▸

11 min

—

with

Why did the dinosaurs go extinct? Because they didn’t have a space program.

▸

4 min

—

with

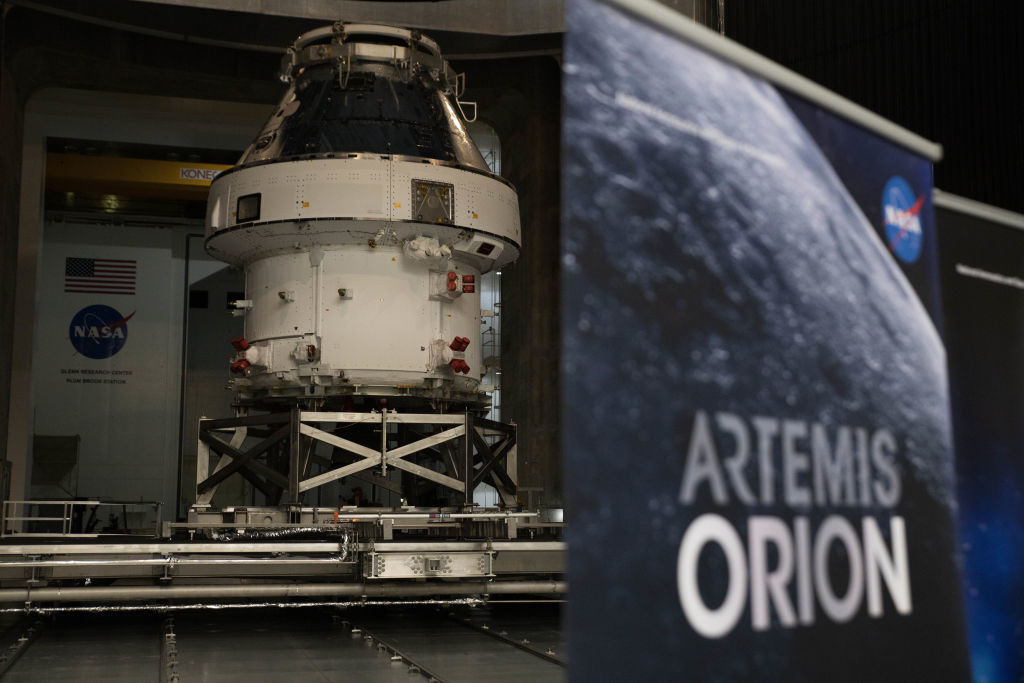

The space agency is ready to establish a base camp by 2024.

The racing plane is hoped to be the fastest electric plane in existence.

Following two deadly crashes, the FAA has been engaged in a lengthy review process of the Boeing 737. With recent news that the review may continue into 2020, Boeing has opted to halt production of the plane.

The space station sector has exciting potential as more private companies enter the conversation.

▸

6 min

—

with

New technology offers us a look at the green future of aviation and cargo shipping.

The national public charging infrastructure is coming online.

How the half-hour commute and motorised transport changed our cities into huge metropolises.

Combined with high-capacity public transport, AVs could remove 9 out of every 10 cars in a mid-sized European city.

An elegant, 400-year-old means of navigating the stars takes flight.

Average waiting time for hitchhikers in Ireland: Less than 30 minutes. In southern Spain: More than 90 minutes.

The Hermeus Corporation recently received seed funding to begin building a hypersonic jet that would travel twice the speed of the now-retired Concorde.

Unfortunately, this means that drivers act more aggressively on the road when spotting cyclists.

Archeologists had been doubtful since no such ship had ever been found.

Less than a mile long, the Dorfbahn in Serfaus is also the world’s highest metro system.

North Korea’s Great Leader would rather not fly for his second summit with Trump – but the trip is also a political message to China.

In 2008, Elon Musk explained which of history’s tech geniuses was his role model.

▸

with

It may create the conditions for further inequality.