social change

The US prison system continues to fail, so why does it still exist?

▸

18 min

—

with

Fifty years of research on children’s toy preferences shows that kids generally prefer toys oriented toward their own gender.

New research sheds light on the indoctrination process of radical extremist groups.

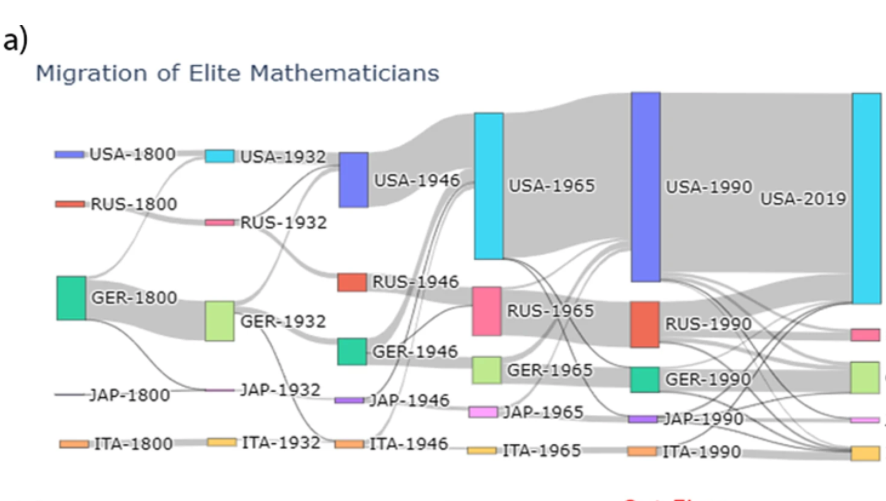

The Field Medal was created to elevate promising mathematicians from underrepresented demographics. But has it followed through on that goal?

For some philosophers, hope is a second-rate way of relating to reality.

How the German political philosopher called out Henry David Thoreau on civil disobedience.

If more people decide to apply pressure through their choices, slowly but surely we would reach climate change herd immunity.

One bill hopes to repeal the crime of selling sex and expand social services; the other would legalize the entire sex trade.

Even tyrants and despots offer wisdom worth heeding.

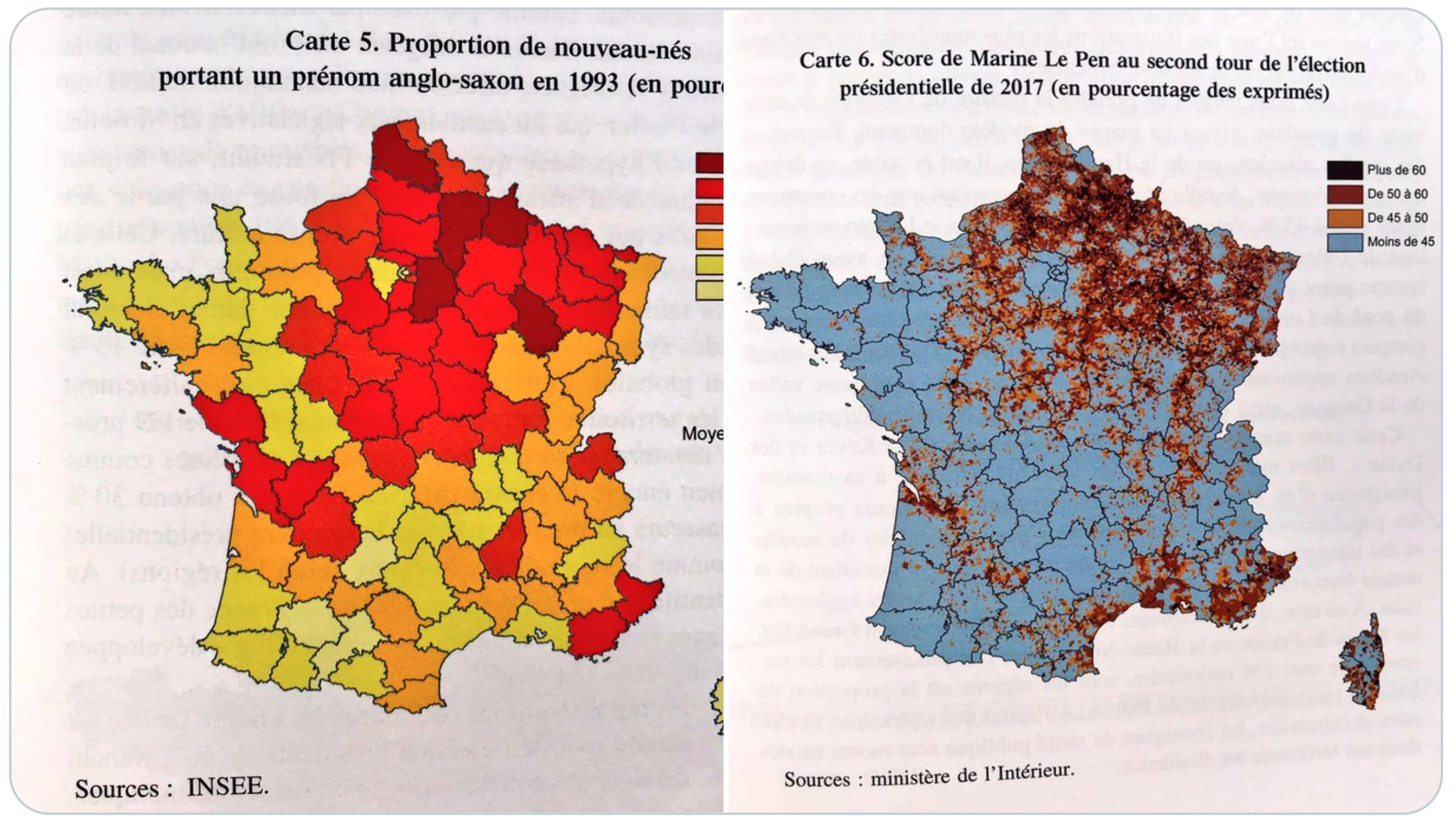

In Germany and France, having an Anglo-Saxon first name is a good predictor of extreme voting behavior.

The platform experiments with letting users decide what content needs flagging.

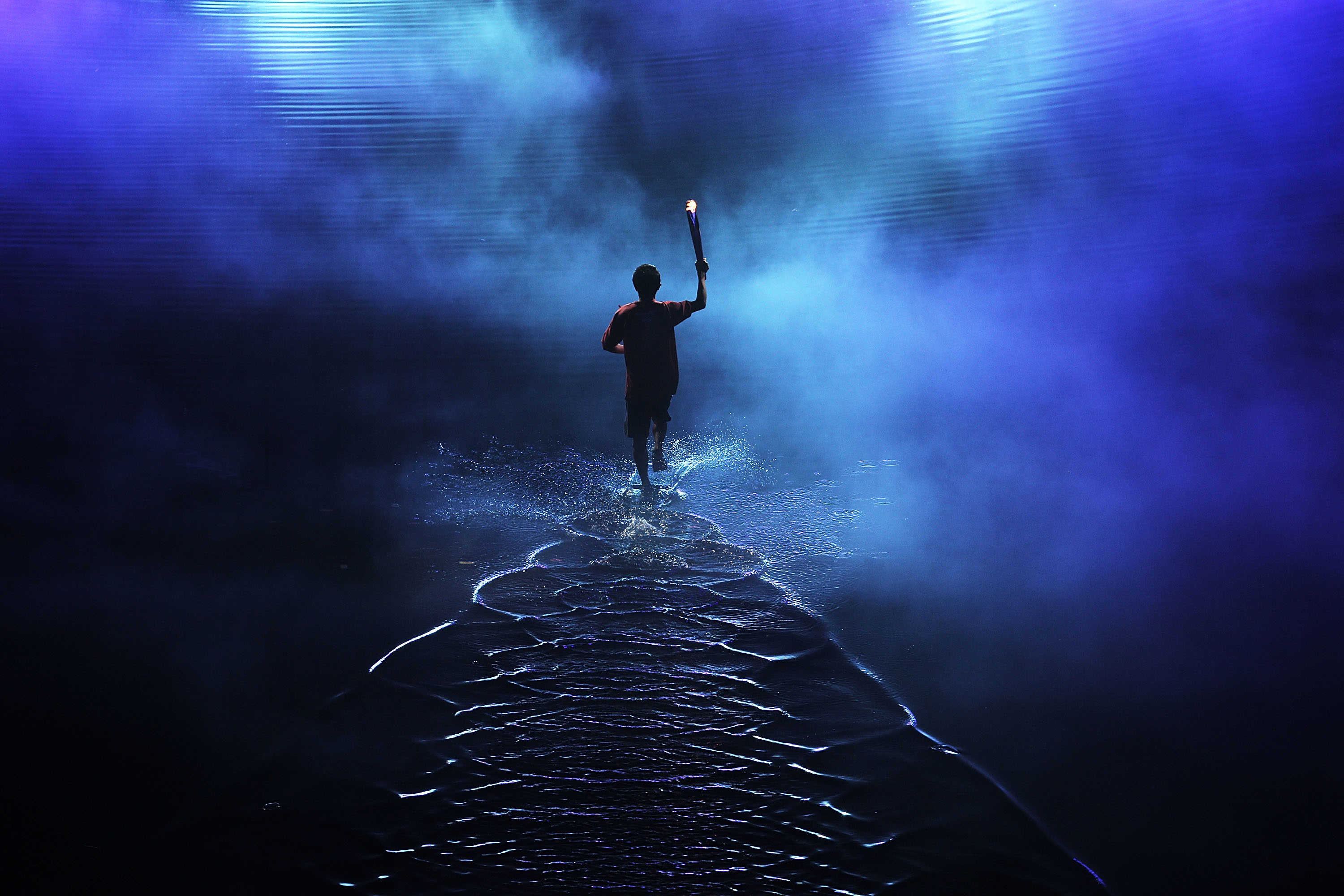

The next era in American history can look entirely different. It’s up to us to choose.

▸

5 min

—

with

We have the money to change the world. What’s standing in the way?

▸

4 min

—

with

‘Critical Tourist Map of Oslo’ offers uniquely dark perspective on Norway’s capital.

In this 1915 map, Lady Liberty shines her light in the West on women in the East, still in electoral darkness

Anastasia lives alone in perfect harmony with nature – or so the story goes – and nature serves her devotedly.

A persistent barrage of information is not the best method for getting through to someone with a different point of view.

▸

5 min

—

with

Perhaps downhill and cross-country skiers don’t face the fate of potters, typesetters and saddlers, but their situation is certainly unclear.

A new study shows how poor children are negatively impacted neurologically.

What would happen if you tripled the US population? Matthew Yglesias and moderator Charles Duhigg explore the idea on Big Think Live.

▸

with

The survey, performed by Morning Consult and commissioned by Amazon, found a majority of those job seekers want to move into new industries to stay relevant.

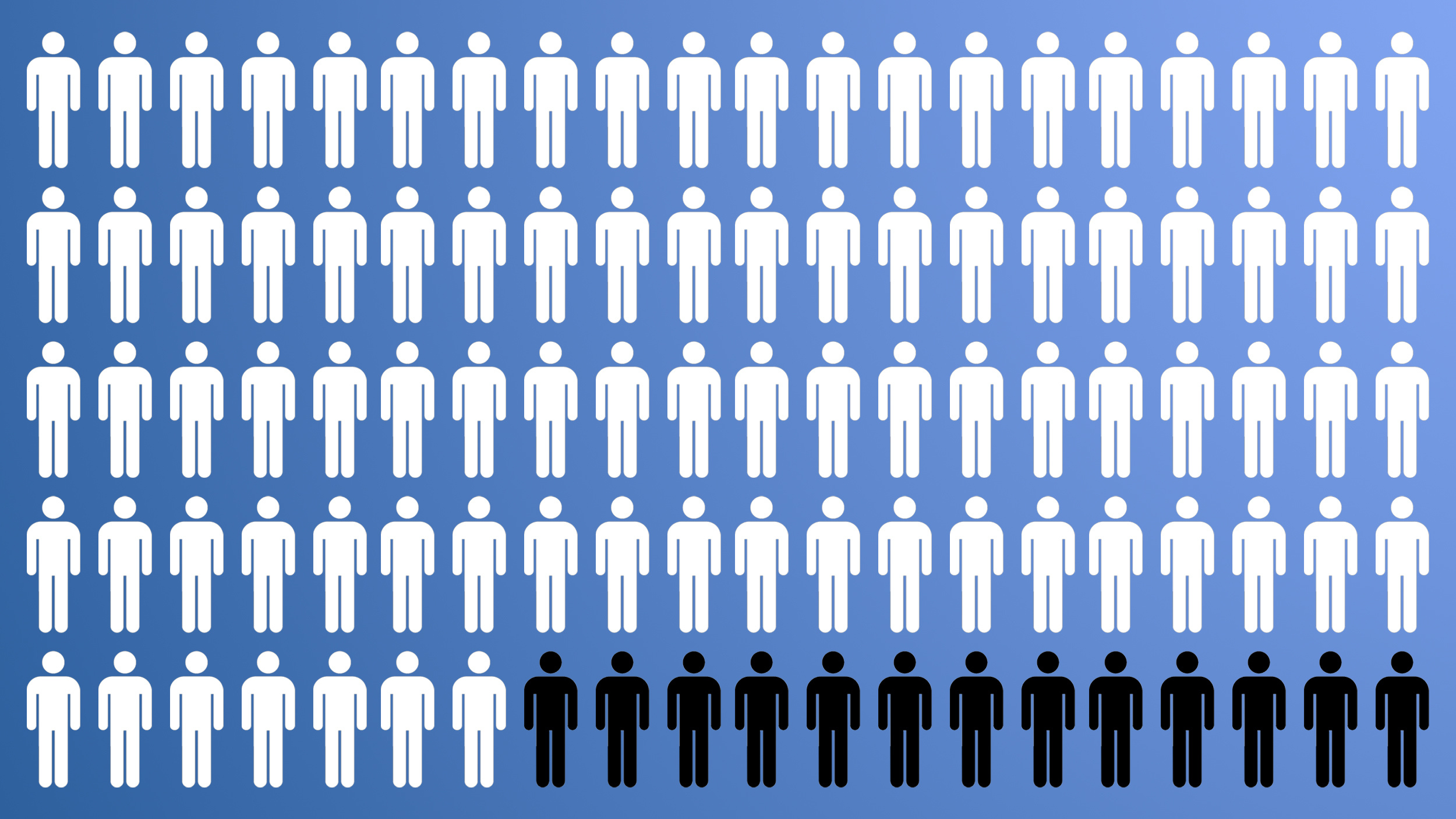

Less than 1% of all venture capital funding in the US is given to Black entrepreneurs. Now is the time for that to change.

Estonia has combined a belief in learning with equal-access technology to create one of world’s best education systems.

The American economy may be locked into an unhealthy cycle that only benefits a select few. Is it too late to fix it?

▸

19 min

—

with

Mexico City, already progressive, takes more steps to protect its LGBT+ citizens.

The Silicon Valley titan has promised scholarships for its tech-focused certificate courses alongside $10 million in job training grants.

Despite fact check campaigns, anti-vaccination influence is growing.

The word “learning” opens up space for more people, places, and ideas.

▸

3 min

—

with

Seldom are these conversations actually anti-racist.