ptsd

As a new industry emerges, therapists need to be educated.

A new study shows that beauty standards affect whether or not accusers are believed.

No, being interested in BDSM does not mean you had a traumatic childhood.

A large-scale meta-analysis aims to disprove the notion that pornography consumption causes sexual aggression and violence.

A team of researchers have discovered the brain rhythmic activity that can split us from reality.

Symptoms of mental illness in children are often dismissed as “going through a phase.”

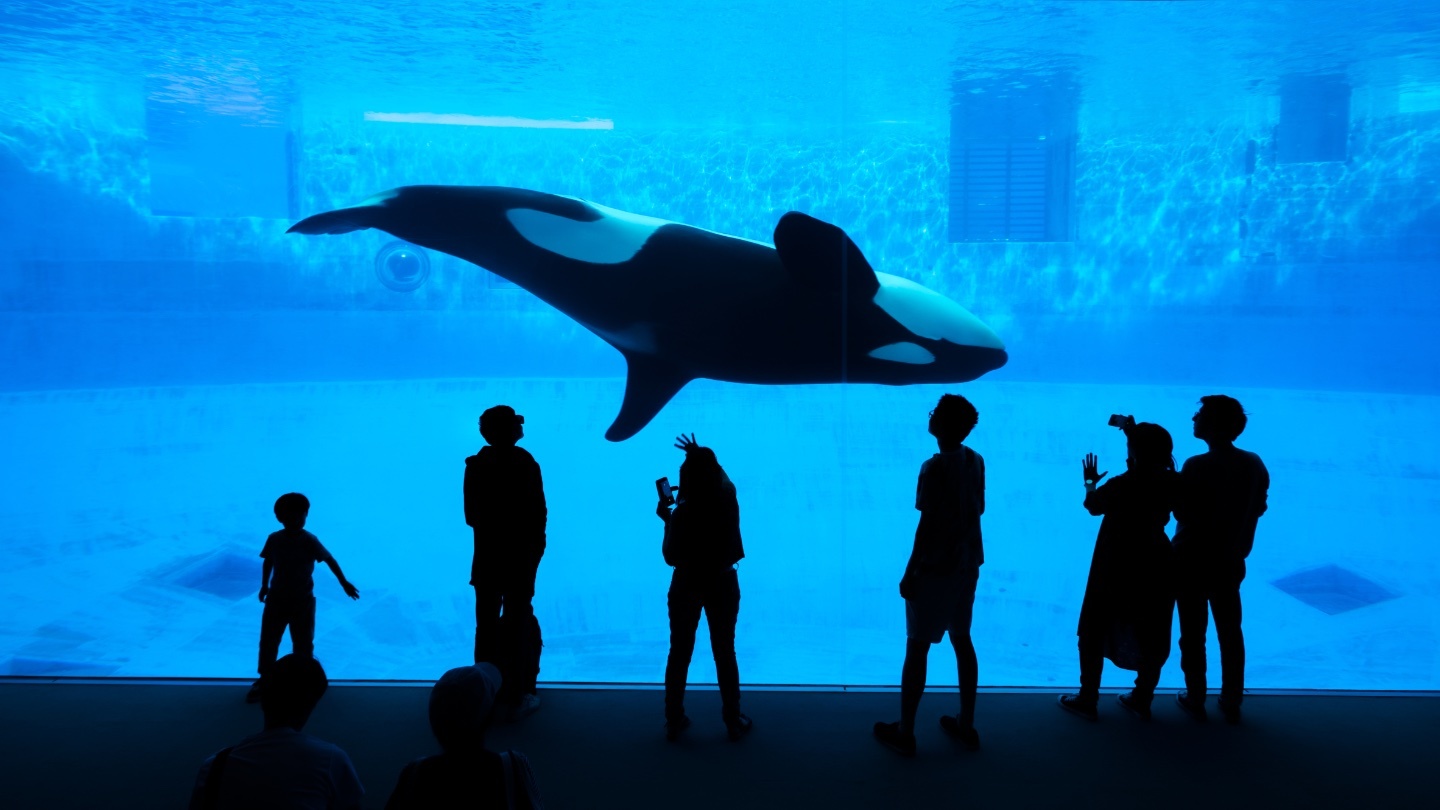

A new study lays out the case for the damaging effects of stress on orcas living in tanks.

An algorithm may allow doctors to assess PTSD candidates for early intervention after traumatic ER visits.

A groundbreaking Stanford University study explains the areas of the brain that are impacted by hypnosis.

There are countless studies that prove ecotherapy (often referred to as nature therapy) is beneficial for your physical and mental health.

An inside look at common relationship problems that link to how we were raised.

Researchers make breakthrough in studying traumatic long-term memory in flies.

A deeper look at what happens in the first 2 years after experiencing sexual trauma.

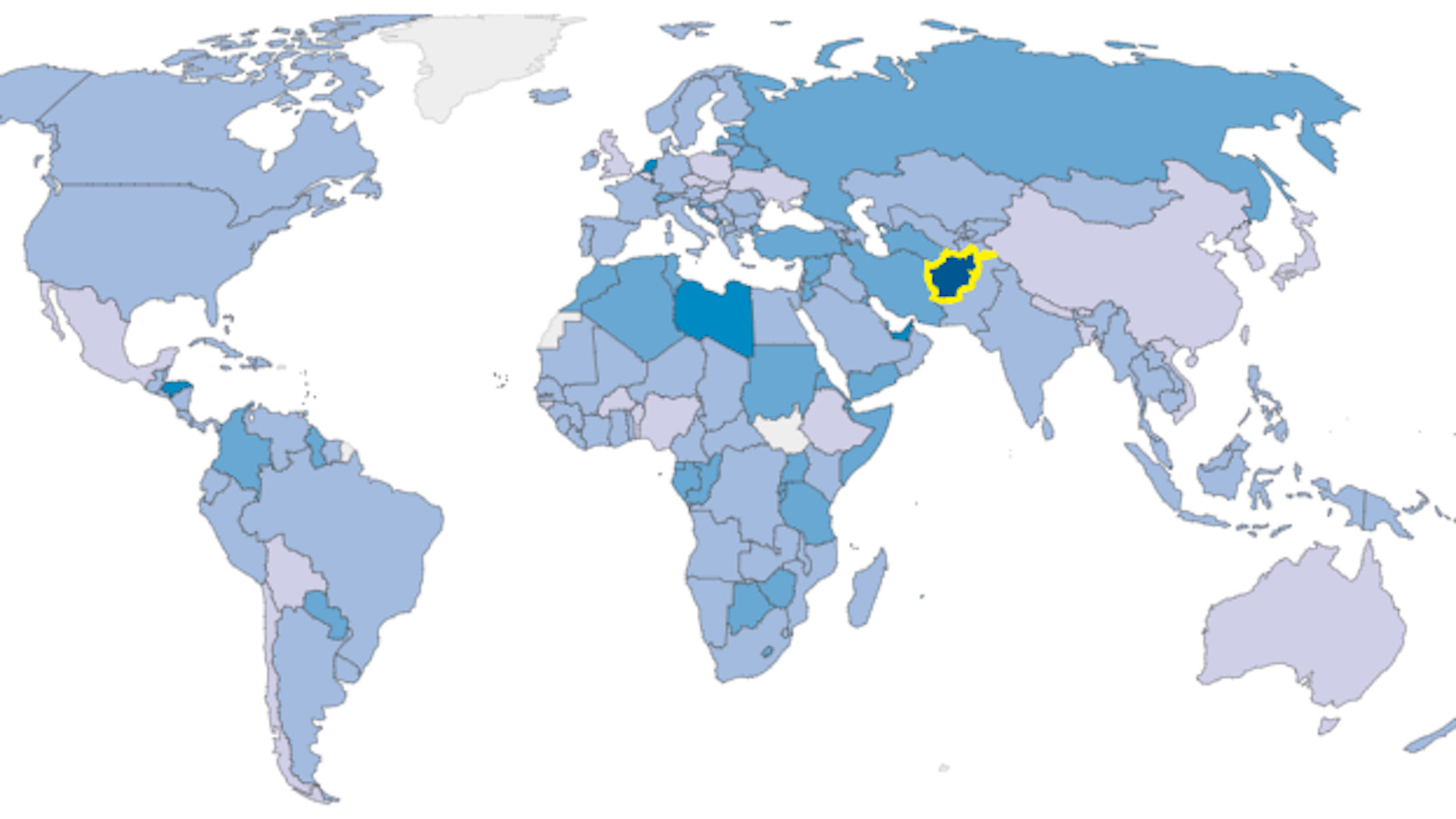

Proponents of drones in foreign conflicts argue that it reduces harm for civilians and U.S. military personnel alike. Here’s why that might be wrong.

▸

with

Researchers discover that not only can anxiety prevent you from sleeping, but not getting a good night’s sleep might also cause anxiety.

So why should we keep using them?

Mycologist Paul Stamets believes they should be.

Researchers measured high- and low-adversity participants’ feelings of compassion.

Anxiety provoked by an unavoidable threat — like an electric shock in a lab — increases as the expected event draws closer.

This modern therapy technique has been shown to be effective and easy to learn — could teaching it to students help cut off a growing mental health crisis?

Activist and Big Think reader Roy M. Arce explains his idea for a new community policing team and how it can halt vicious cycles of PTSD and homelessness.

Can dirt help us fight off stress? Groundbreaking new research shows how.

Without a healthy mind, tackling life’s challenges becomes exponentially more difficult.

A new study shows success in a series of Phase 2 trials.

No, depression is not just a type of “affluenza” — poor people in conflict zones are more likely candidates

Taking care of our minds is an often neglected aspect of aging. What are we going to do about it?

A recent study could help improve treatments for PTSD, anxiety and phobias.

A supervised learning algorithm can predict clinical depression much earlier and more accurately than trained health professionals.