gender

New research from the University of Granada found that stress could help determine sex.

New research shows that experiencing an opposite-sex body in virtual reality impacted the subject’s gender identity.

A study of the Mosuo women, known for their matriarchy, suggests that gender roles can influence our health outcomes.

Turns out gender assumptions have been going on for quite some time.

The color of toys has a much deeper effect on children than some parents may realize.

▸

6 min

—

with

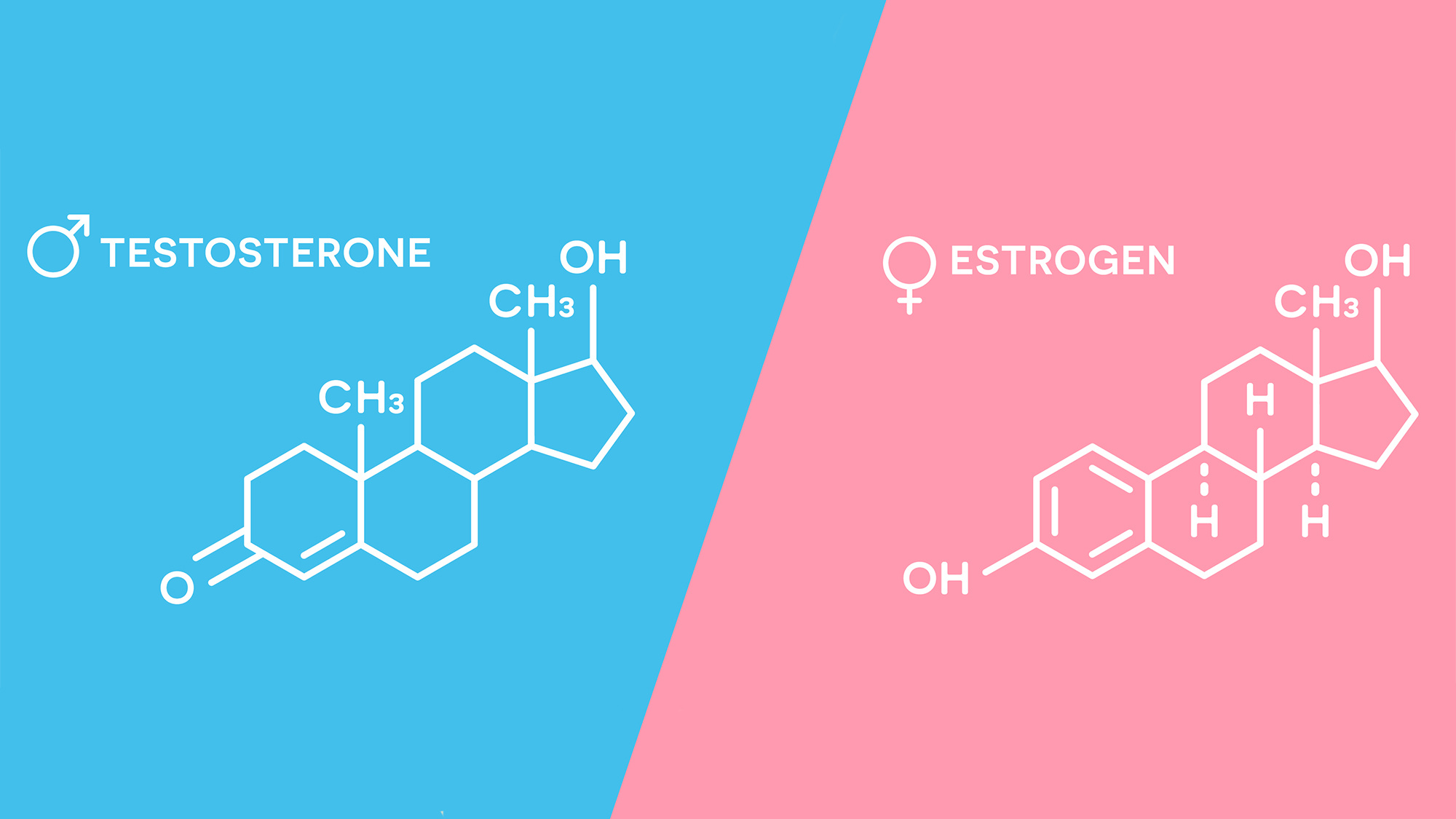

Are there innate differences between female and male brains?

A new study on brain differences between sexes sparks a persistent question.

A general reorganisation of masculine norms interrupted the shaving-respectability regime.

In spite of a government mandate, females are often treated as afterthoughts in scientific research.

Women and girls must be front and centre of coronavirus response and recovery.

A 12-year long study examines the differences between how same-sex and different-sex couples argue, with some surprising results.

Sexuality is fluid and it’s important that people get to define it for themselves.

What factors explain the gender pay gap?

We as a society need to rethink the way we value careers over everything else.

▸

3 min

—

with

More rules is not what’s going to stop sexual harassment at work, says Johnny C. Taylor, Jr. Change the culture.

▸

5 min

—

with

What good is diversity without inclusion?

▸

4 min

—

with

People who score highly on the dark triad are vain, callous, and manipulative.

Striving for diversity is honorable — but the focus should settle on something much deeper than phenotypic traits.

▸

4 min

—

with

University of Utah research finds that men are especially well suited for fisticuffs.

Or is “the hidden orientation” more complex than that?

Whether or not women think beards are sexy has to do with “moral disgust”

What a group of orphaned elephants can teach us about emotion and learned social skills.

▸

3 min

—

with

Taking the fourth spot on Big Think’s 2019 top 10 countdown is the question: Evolutionarily speaking, is being gay still something of an enigma?

▸

10 min

—

with

Iceland has closed almost 88% of its gender gap and increased its lead over second-ranked Norway.

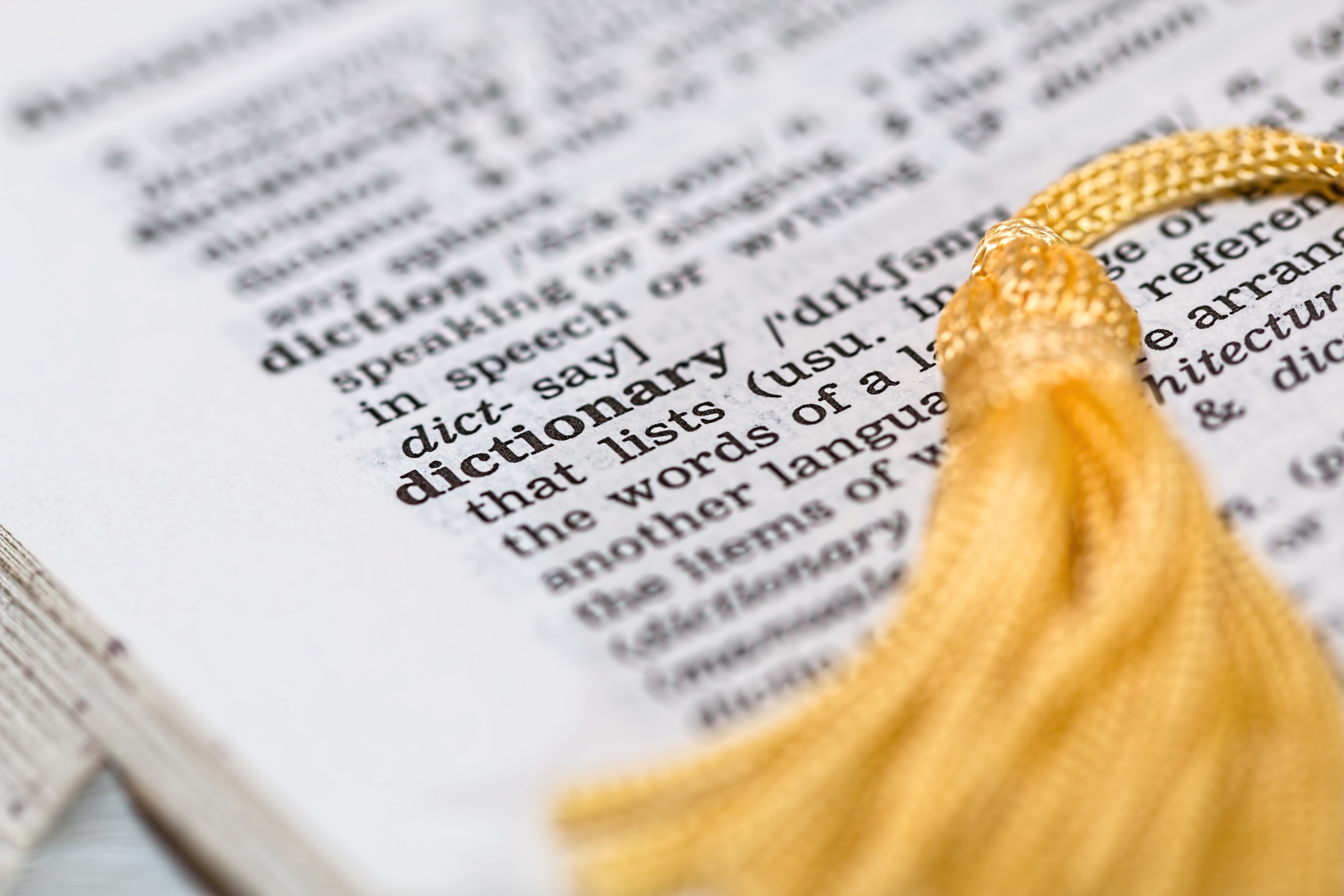

“They” has taken on a not-so-new meaning lately. This earned it the scrutiny it needed to win.

Some lingerie lines have failed to keep up with a new era.

Many people often continue to harbour positive feelings towards their exes long after the relationship is over.

New research finds how power dynamics shape the speech of men and women.

Overcoming assumptions when it comes to gender and capabilities is the key to a successful society.

▸

4 min

—

with

What image of femininity is subtly imposed on us in the war against toxic masculinity?