children

Medical science can save lives, but should it do so at the cost of quality of life?

Birthrates are cyclical and have gone up and down throughout history.

Like autism, ADHD lies on a spectrum, and some children should not be treated.

Did the 20th century bring a breakthrough in how children are treated?

Healthy people need healthy microbiomes from an early age.

The answer seems to be a series of evolutionary trade-offs that help protect organs in women, according to a recent study.

And is anyone protecting children’s data?

Fifty years of research on children’s toy preferences shows that kids generally prefer toys oriented toward their own gender.

Children with pre-existing mental health issues thrived during the early phase of the pandemic.

Escaping the marshmallow brain trap.

▸

6 min

—

with

A 50-year study reveals changing values children learned from pop culture.

Flying that helicopter too low is counterproductive.

These DIY learning kits focus on topics like coding, robotics, and AI, and are on sale for as low as $41.99.

A tourist generally has an eye for the things that have become almost invisible to the resident.

Why do we deprive students of the historical and cultural context of science?

How would the ability to genetically customize children change society? Sci-fi author Eugene Clark explores the future on our horizon in Volume I of the “Genetic Pressure” series.

Scientists ripped up kids’ drawings. This is what they learned about relationships.

▸

5 min

—

with

Having grown kids still at home is not likely to do you, or them, any permanent harm.

A recent NIHR report found that students with previously low connectedness scores saw improvement in well-being and eased anxiety.

The researchers say their findings support the idea that low biodiversity in modern living environments could lead to “uneducated” immune systems.

The color of toys has a much deeper effect on children than some parents may realize.

▸

6 min

—

with

The ability to speak up and ask will give these future leaders a much needed boost.

▸

3 min

—

with

We make school kids read “Lord of the Flies”—but it’s only half the story.

▸

5 min

—

with

“Such studies will lead to a better understanding of brain development in both autistic and typical individuals.”

The area of the brain that recognizes letters and words is ready for action right from the start.

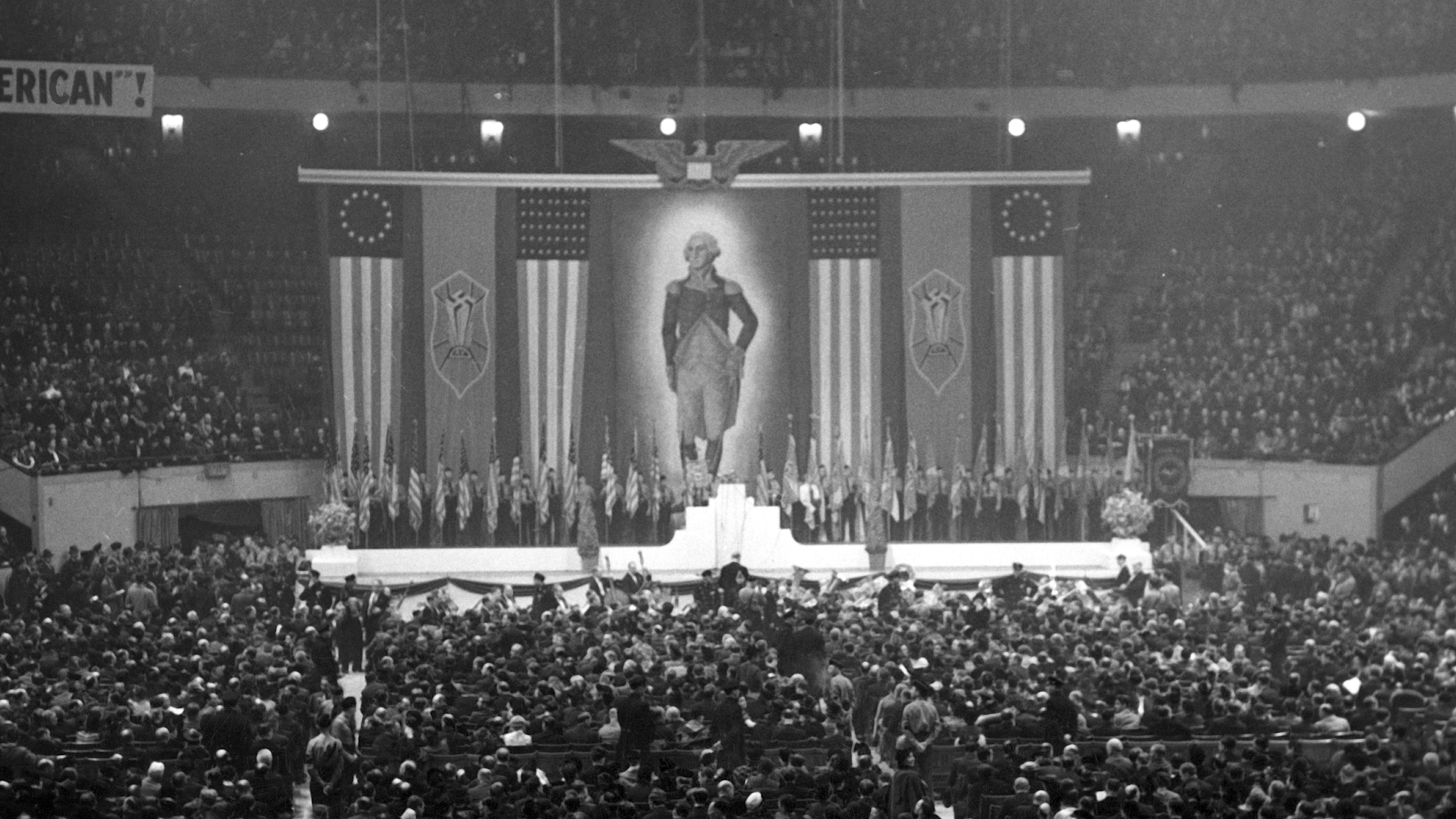

Nazi supporters held huge rallies and summer camps for kids throughout the United States in the 1930s.

While the benefits of music therapy are well known, more in-depth research explores how music benefits children with autism.

‘Little kids, little problems; big kids, big problems.’

A new study collected 500 data points per second. Handwriting won out.