addiction

The Osbournes was MTV’s biggest show – and it almost cost Jack Osbourne his life. Here’s how his family’s reality TV fame stole his childhood, and how he’s been able to heal since.

▸

6 min

—

with

If love is an addiction, your first love is the first dose.

Fear that new technologies are addictive isn’t a modern phenomenon.

Some of these trends may be due, in part, to the lockdown.

Our program lowers reincarceration rates by 44 percent.

Israeli food-tech company DouxMatok (Hebrew for “double sweet”) has created a sugary product that uses 40 percent less actual sugar yet still tastes sweet.

A new study looks at how images of coffee’s origins affect the perception of its premiumness and quality.

New study suggests the placebo effect can be as powerful as microdosing LSD.

A new study explores the therapeutic potential of the psychedelic drug ibogaine, which has been used in Africa for centuries.

The compound found in “magic mushrooms” has significant and fast-acting impact on the brains of rats.

What is more important, that a treatment helps keep people healthy or that it meshes with our morals?

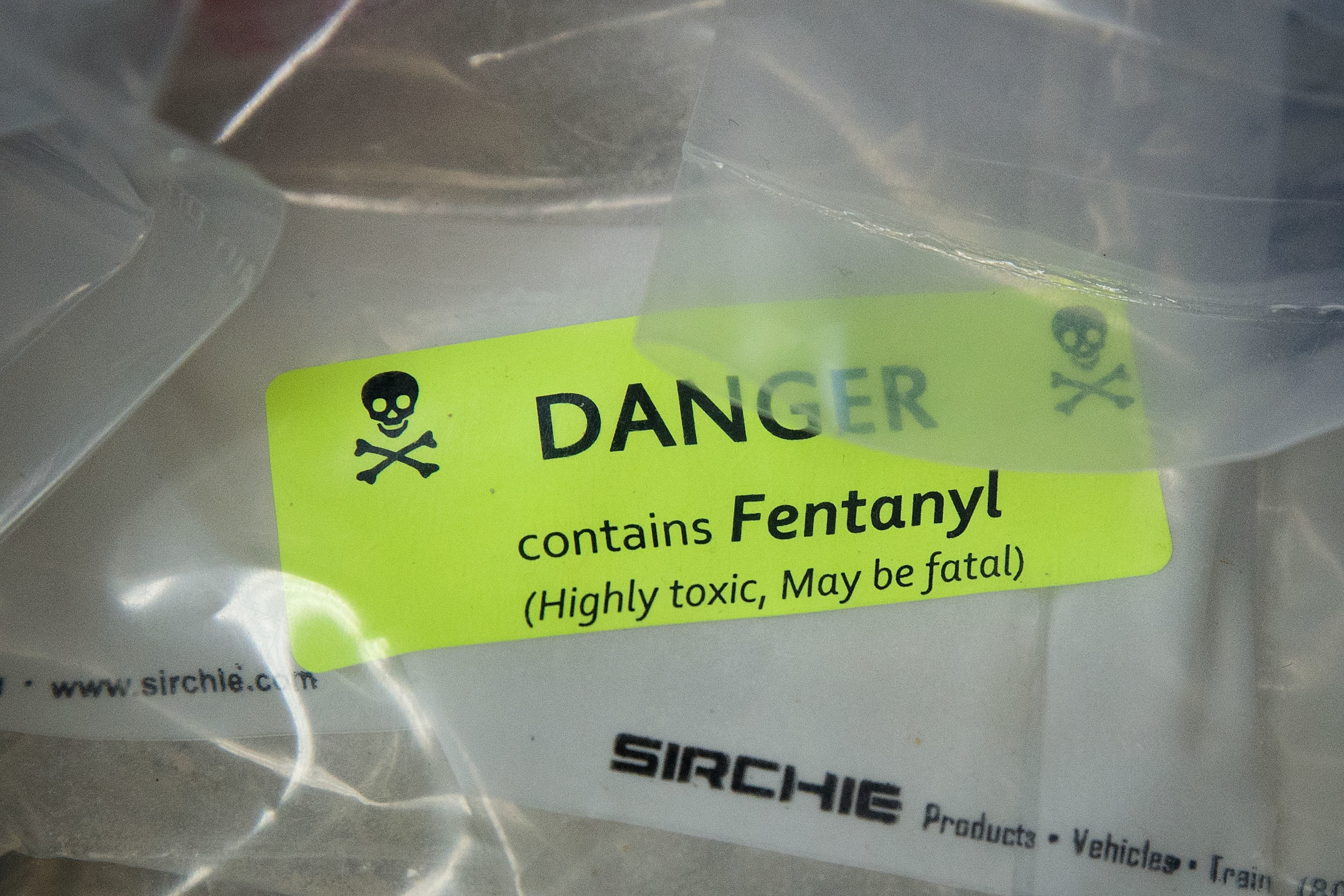

There has been a dramatic increase in abuse and misuse.

We owe a lot to vaccines and the scientists that develop them. But we’ve only just touched the surface of what vaccines can do.

▸

17 min

—

with

New research conducted on mice suggests repeated heavy drinking causes synaptic dysfunctions that lead to anxiety.

A large-scale study from King’s College London explores the link between genetics and sun-seeking behaviors.

A small proof-of-concept study shows smartphones could help detect drunkenness based on the way you walk.

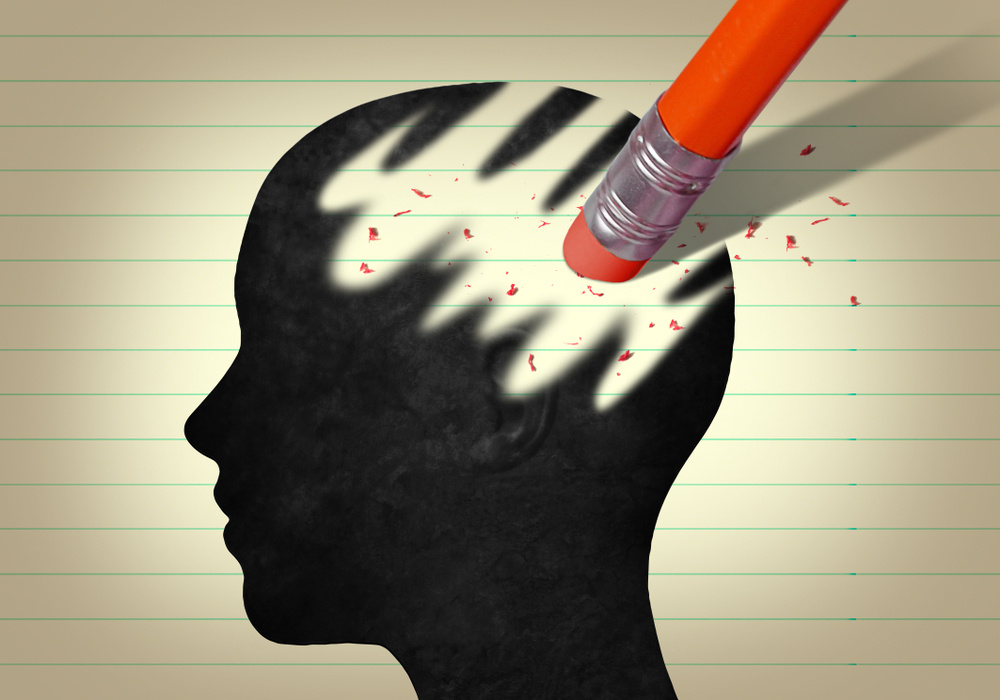

New research conducted on the brains of mice suggest it may be possible to “switch off” particular food cravings.

Addiction is not a moral failure. It is a learning disorder, and viewing it otherwise stops communities and policy makers from the ultimate goal: harm reduction.

▸

19 min

—

with

The 2020 study successfully removed memories associated with morphine from the brains of mice with very promising results.

How exactly is COVID-19 affecting the opioid crisis?

Attending religious service once a week found to lower risk of suicide and other “deaths of despair”

In late April, the news hit us hard: Lorna Breen, an emergency room doctor in a Manhattan hospital flooded with coronavirus patients, committed suicide. According to her father, the emotional […]

Being aware of this issue is a big first step in helping vulnerable communities (such as those struggling with addiction) combat relapse during this pandemic.

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen might have discovered a cure.

The key to raising indistractable kids is to first determine why they’re distracted.

▸

4 min

—

with

A new study on rats suggests that using marijuana as an adolescent “reprograms the initial behavioral, molecular, and epigenetic response to cocaine.”

Simple tricks for hacking back your device.

▸

2 min

—

with

This video game designer’s creations have been said to work “neurological magic.”

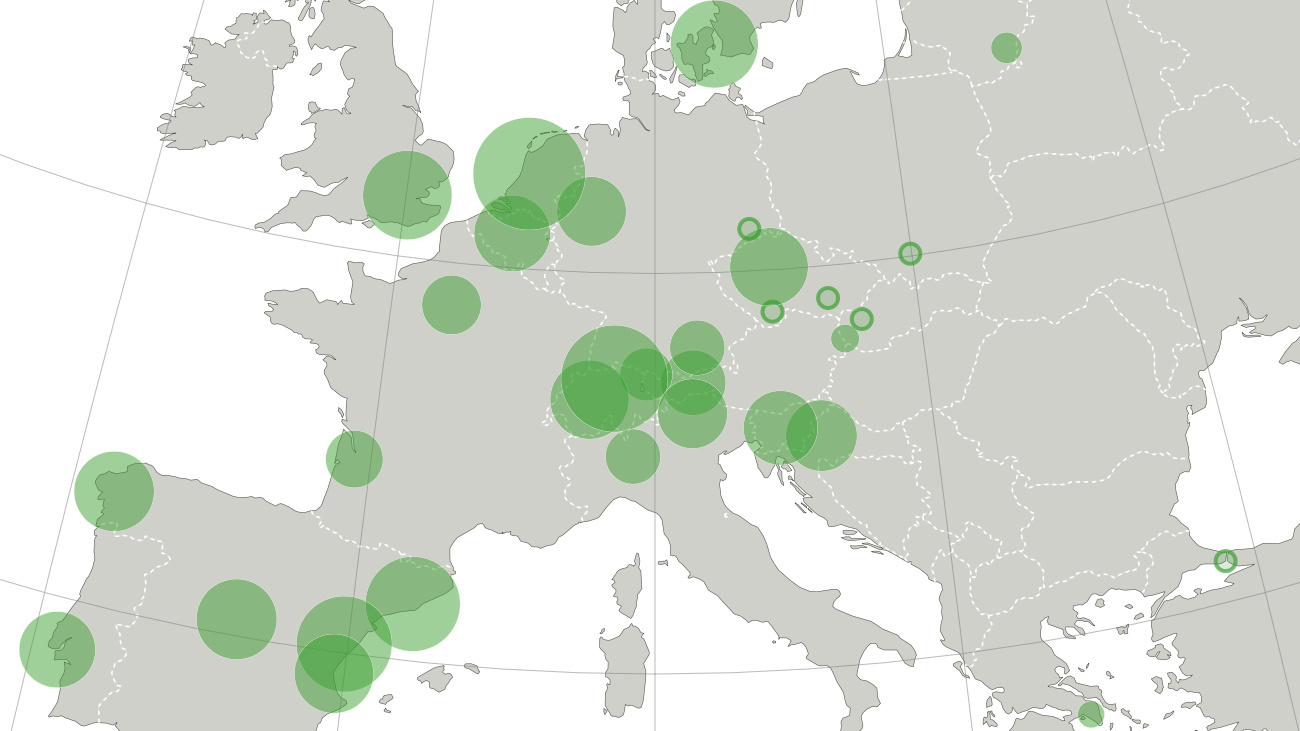

Coke, meth, ecstasy, amphetamines: each drug has a different ‘capital’

A new drug derived from scorpion venom reversed developmental damage in mice exposed to alcohol during pregnancy.