language

A genetic study of British Columbia grizzly bears finds a weird link to local human languages.

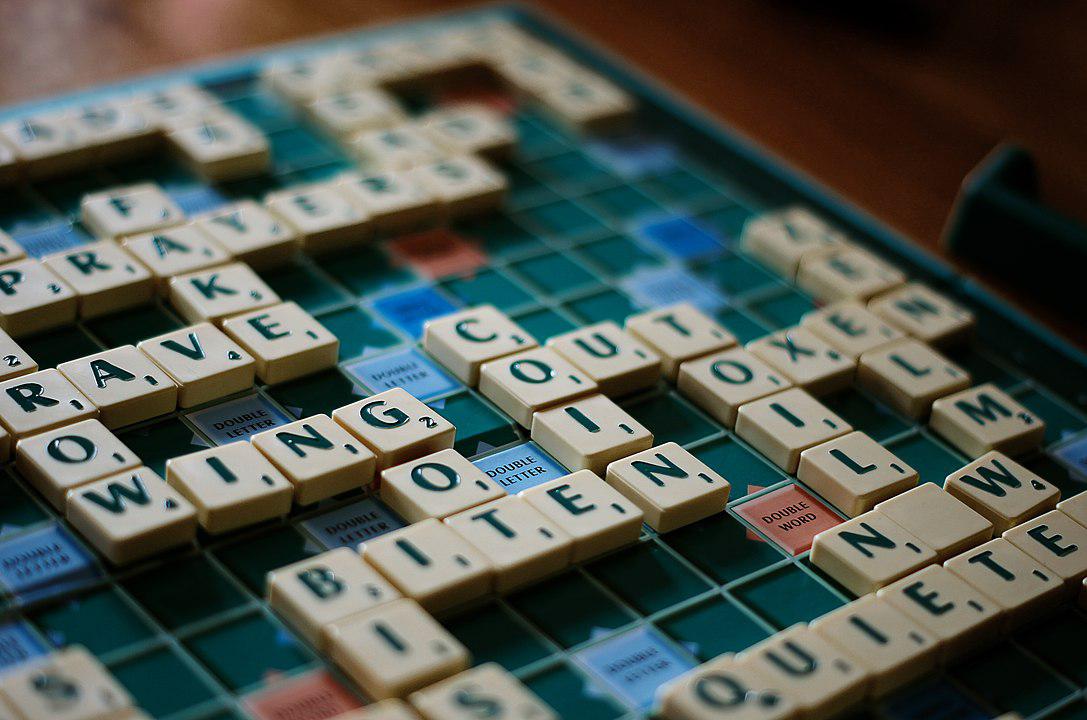

English is a dynamic language, and this summer’s new additions to dictionary.com tell us a lot about how we’re living.

Linguists discover 30 sounds that may have allowed communication before words existed.

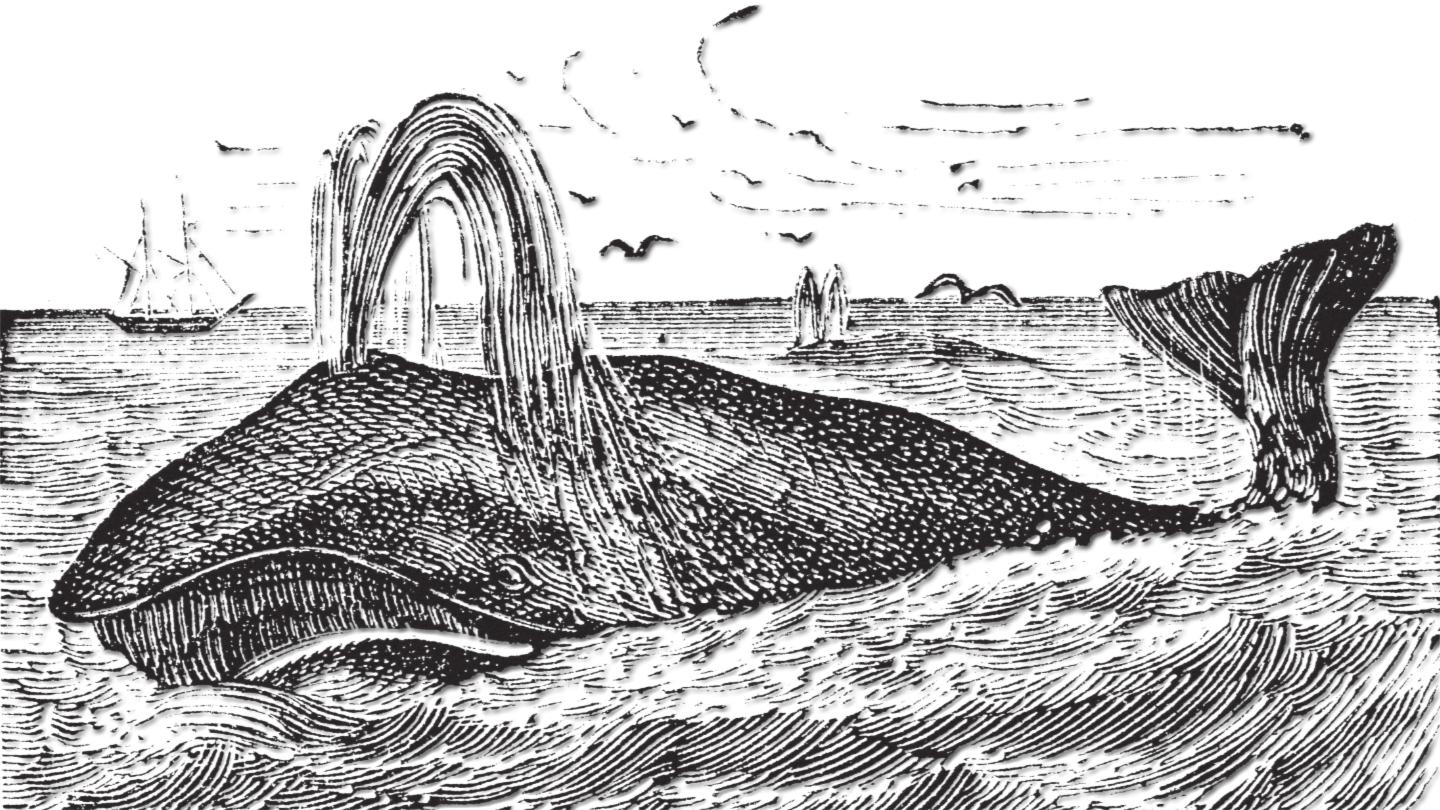

Digitized logbooks from the 1800s reveal a steep decline in strike rate for whalers.

How our brains interpret computer code could impact how we teach it.

The key? A computational flattening algorithm.

Their ear structures were not that different from ours.

The debate over whether or not there is a place for political correctness in modern society is not always black and white.

▸

13 min

—

with

The study found that people who spoke the same language tended to be more closely related despite living far apart.

Reading code activates a general-purpose brain network, but not language-processing centers.

After the unrelenting negativity of 2020, we may need a refresher on the benefits of a positive affect.

It’s never too late to learn a new language. Just don’t count on speaking French like a Parisian.

The area of the brain that recognizes letters and words is ready for action right from the start.

Partisanship can now be seen in brain scans.

While the benefits of music therapy are well known, more in-depth research explores how music benefits children with autism.

A new study shows that naming conventions will change how infants represent objects in their memories.

The English Department is instituting a series of reforms that cuts across the entire university.

Getting what you want often requires choosing the right strategy.

▸

26 min

—

with

Never has the bar to entry been so low and the recognized benefits so high.

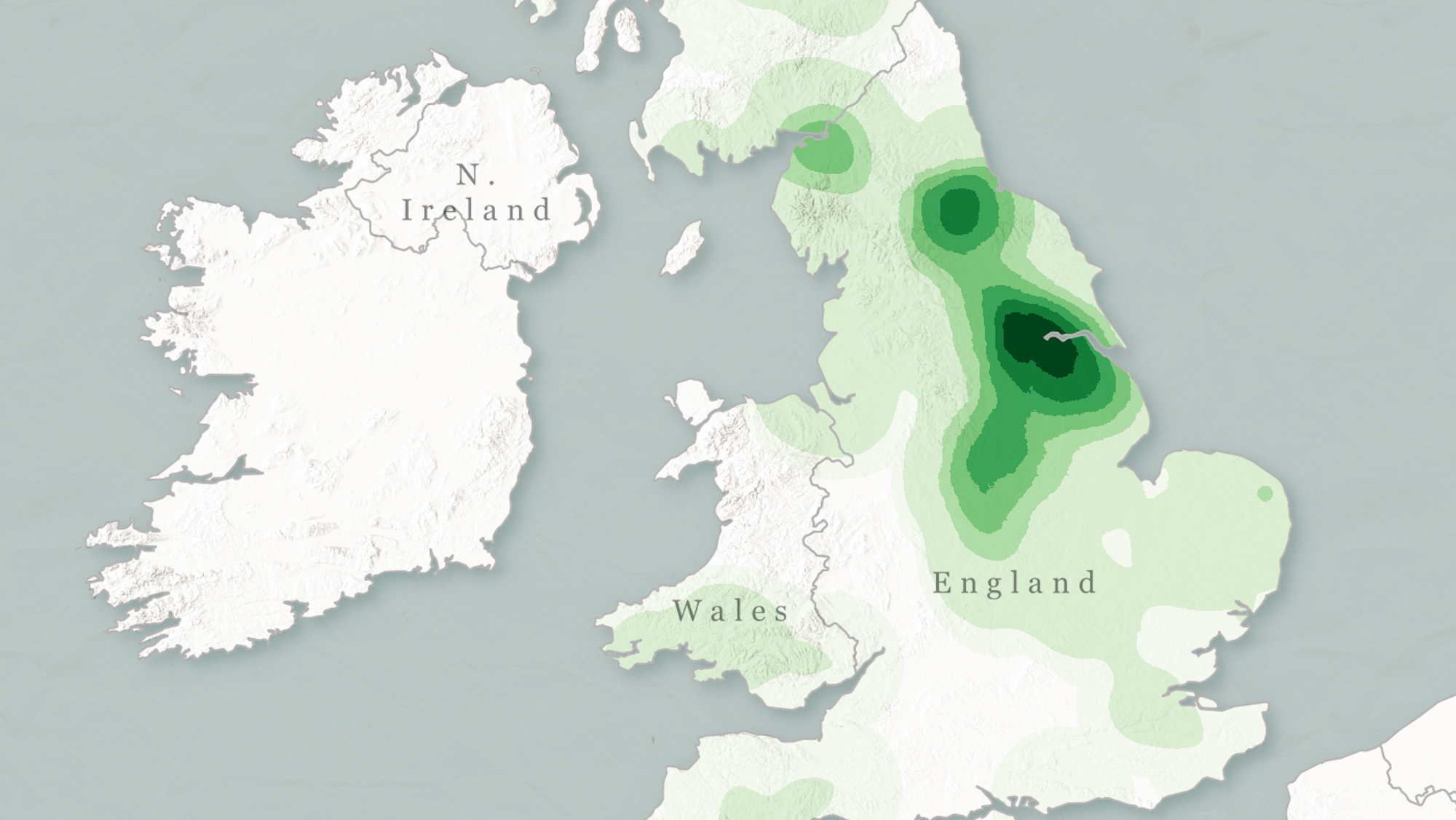

Two remarkable etymological maps show twin forces at work throughout human history.

A new study looks at what would happen to human language on a long journey to other star systems.

A study of the manner in which memory works turns up a surprising thing.

Mapping the frequency of common toponyms opens window on Britain’s ‘deep history’.

The word “learning” opens up space for more people, places, and ideas.

▸

3 min

—

with

Europe is divided on whether films should have subtitles or different audio tracks.

Don’t worry about grammar rules at first. They’ll only trip you up.

▸

3 min

—

with

Mathematicians studied 100 billion tweets to help computer algorithms better understand our colloquial digital communication.

According to a man that knows more than 20 languages, the key is to start in the middle.

▸

4 min

—

with

A larger vocabulary can be a confidence booster for children and make adults better communicators.