humanity

Climate change. War. Civil unrest. Is it responsible to have kids today?

▸

4 min

—

with

He’s studied apes for 50 years – here’s what most people get wrong.

▸

6 min

—

with

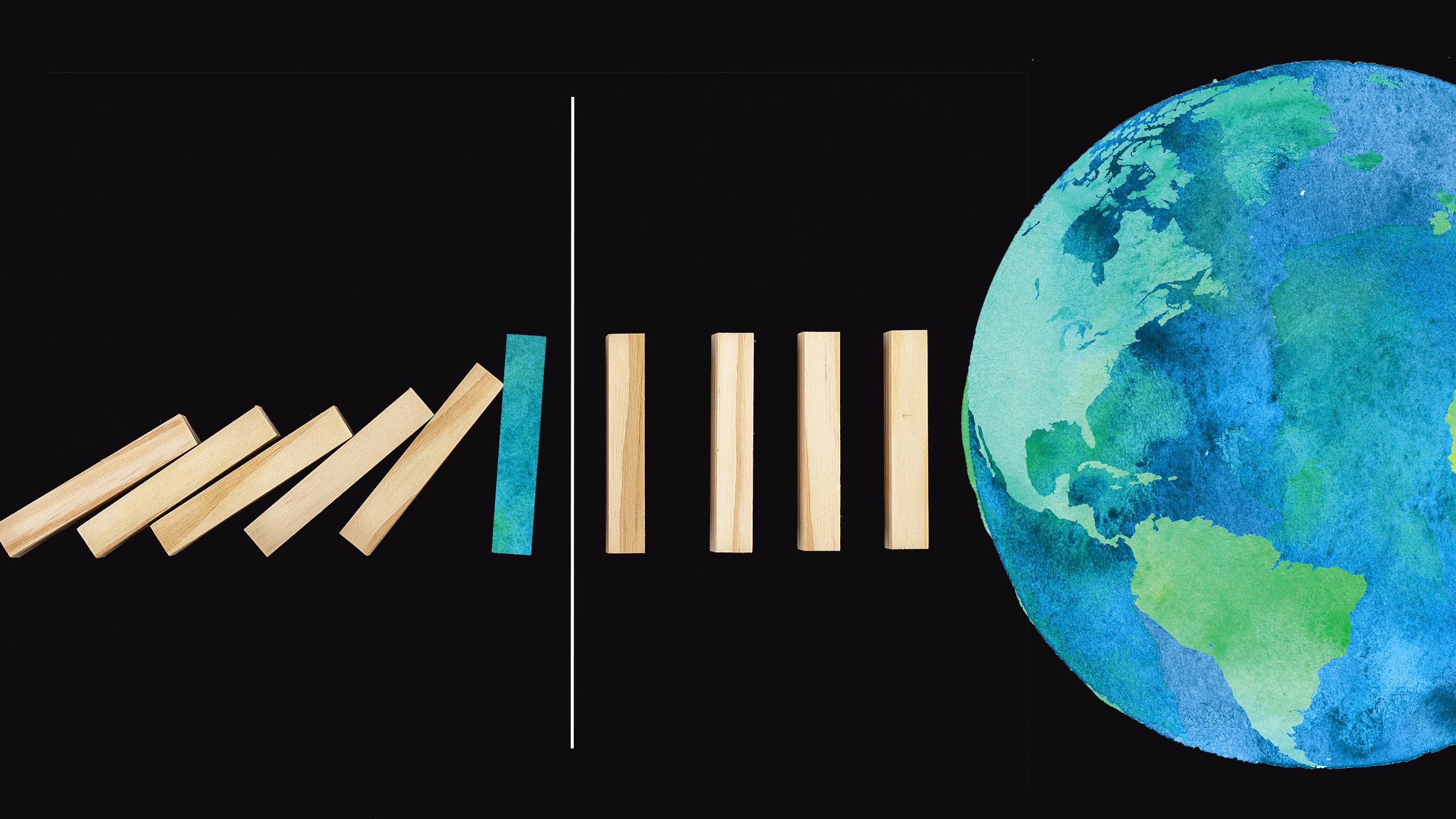

The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis argues that a comet strike caused major changes to climate and human cultures on Earth about 13,000 years ago.

Too few babies — not overpopulation — is likely to be a major problem this century.

Being an intellectual is not really how it is depicted in popular culture.

▸

5 min

—

with

Why are rapture ideologies exploding?

▸

7 min

—

with

How fabric helped build modern civilization.

▸

6 min

—

with

Social interactions are important for building the strongest relationships.

▸

5 min

—

with

Escaping the marshmallow brain trap.

▸

6 min

—

with

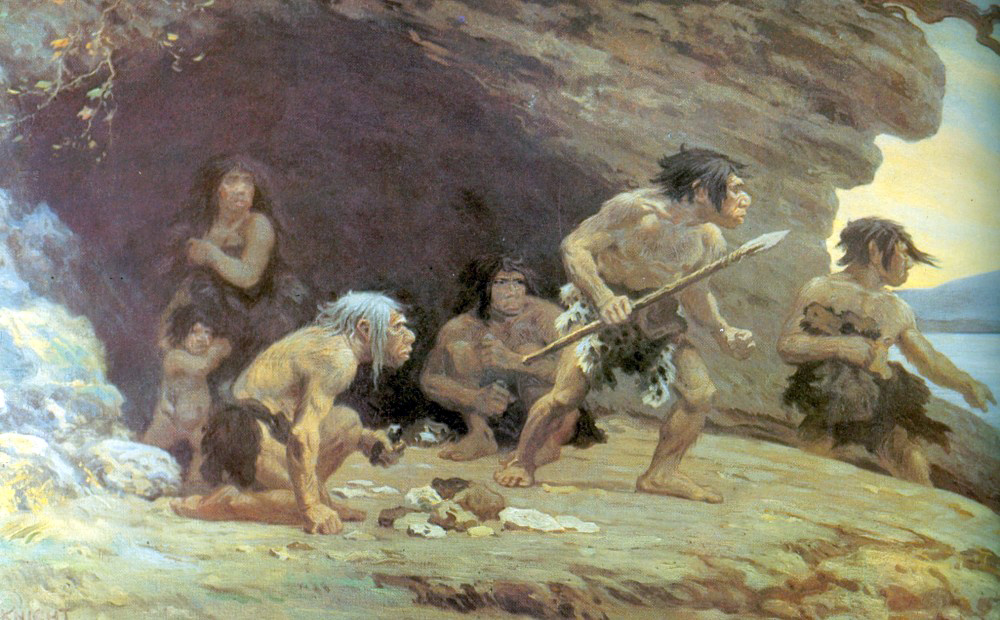

Hunter-gatherers probably had more spare time than you.

75 years after Erwin Schrödinger’s prescient description of something like DNA, we still don’t know the “laws of life.”

Spirituality can be an uncomfortable word for atheists. But does it deserve the antagonism that it gets?

If more people decide to apply pressure through their choices, slowly but surely we would reach climate change herd immunity.

For democracy to prosper in the long term, we need more people to reach higher levels of education.

Technology of the future is shaped by the questions we ask and the ethical decisions we make today.

▸

5 min

—

with

Pandemics have historically given way to social revolution. What will the post-COVID revolution be?

Why do we deprive students of the historical and cultural context of science?

The study found that people who spoke the same language tended to be more closely related despite living far apart.

Dr. Katie Mack explains what dark energy is and two ways it could one day destroy the universe.

▸

9 min

—

with

The expansion of the universe is speeding up—contrary to what many physicists expected. A “heat death” is coming, but it’s not what you think.

▸

7 min

—

with

The search for alien life is far too human-centric. Our flawed understanding of what life really is may be holding us back from important discoveries about the universe and ourselves.

▸

6 min

—

with

An archaeologist considers the history and biology of what defines a taste of home.

Other cultures can differ greatly from your own, but there are commonalties in the way we express emotions.

Is death the final frontier? We ask scientists, philosophers, and spiritual leaders about life after death.

▸

14 min

—

with

What is human dignity? Here’s a primer, told through 200 years of great essays, lectures, and novels.

Radical thinker Rutger Bregman paints a new, more beautiful portrait of humanity.

Historian Rutger Bregman argues that the persistent theory that most people are monsters is just wrong.

▸

6 min

—

with

Synchronous movement seems to help us form cohesive groups by shifting our thinking from “me” to “we.”

To war is human – and Neanderthals were very like us.

We make school kids read “Lord of the Flies”—but it’s only half the story.

▸

5 min

—

with