death

Being mortal makes life so much sweeter.

Even the most unorthodox posthumous plans have their own historical, spiritual, and scientific significance.

Some of these trends may be due, in part, to the lockdown.

Biomedical science assumes that people want to live as long as possible. They don’t.

The experience of life flashing before one’s eyes has been reported for well over a century, but where’s the science behind it?

How do archaeologists know if someone was buried intentionally tens of thousands of years ago?

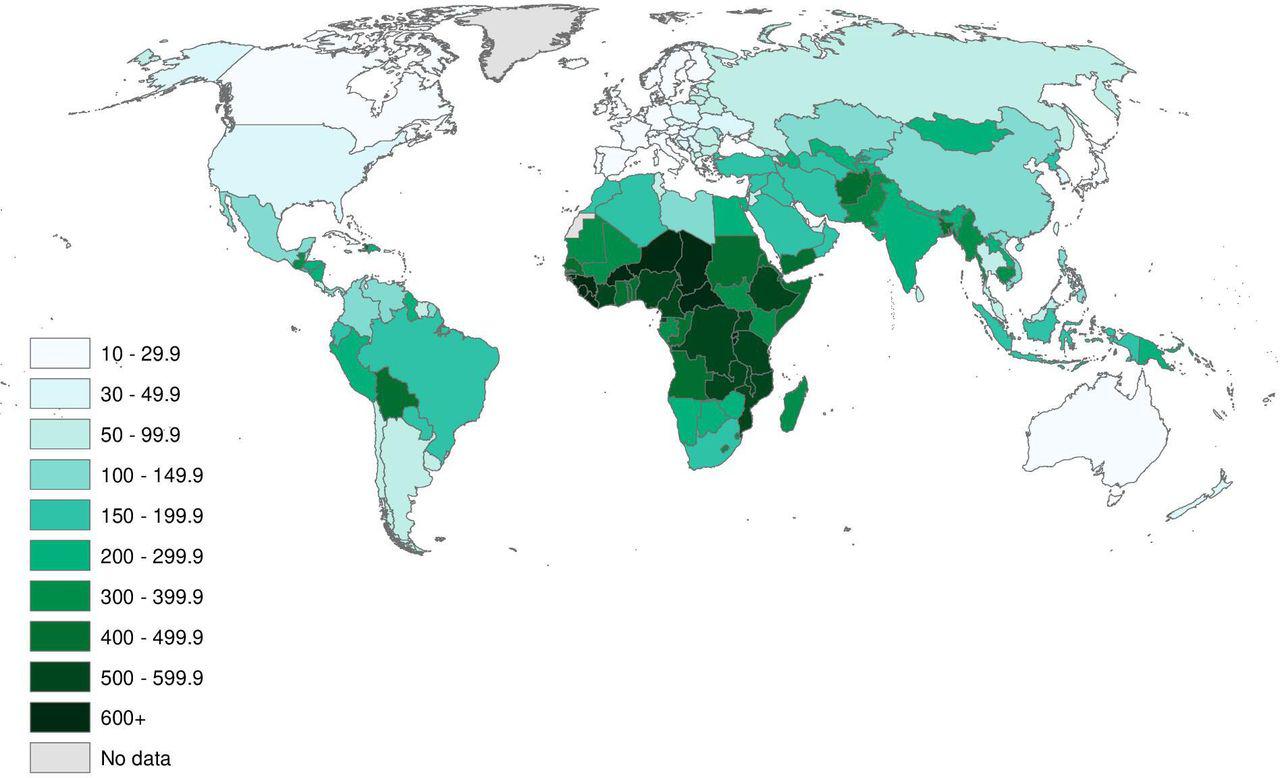

Global inequality takes many forms, including who has lost the most children

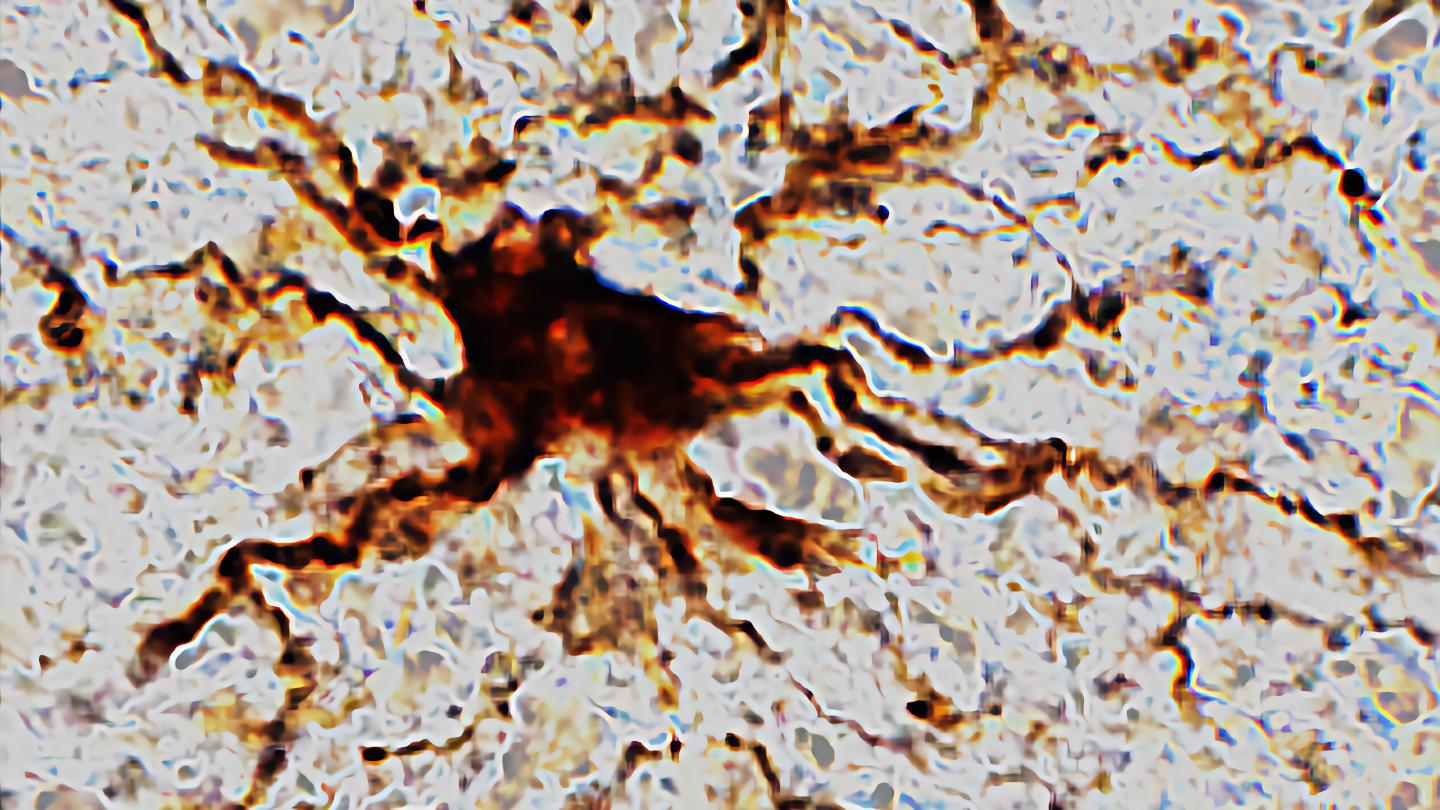

Researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago find that death triggers increased activity in certain brain cells.

As patients approached death, many had dreams and visions of deceased loved ones.

Dr. Katie Mack explains what dark energy is and two ways it could one day destroy the universe.

▸

9 min

—

with

The expansion of the universe is speeding up—contrary to what many physicists expected. A “heat death” is coming, but it’s not what you think.

▸

7 min

—

with

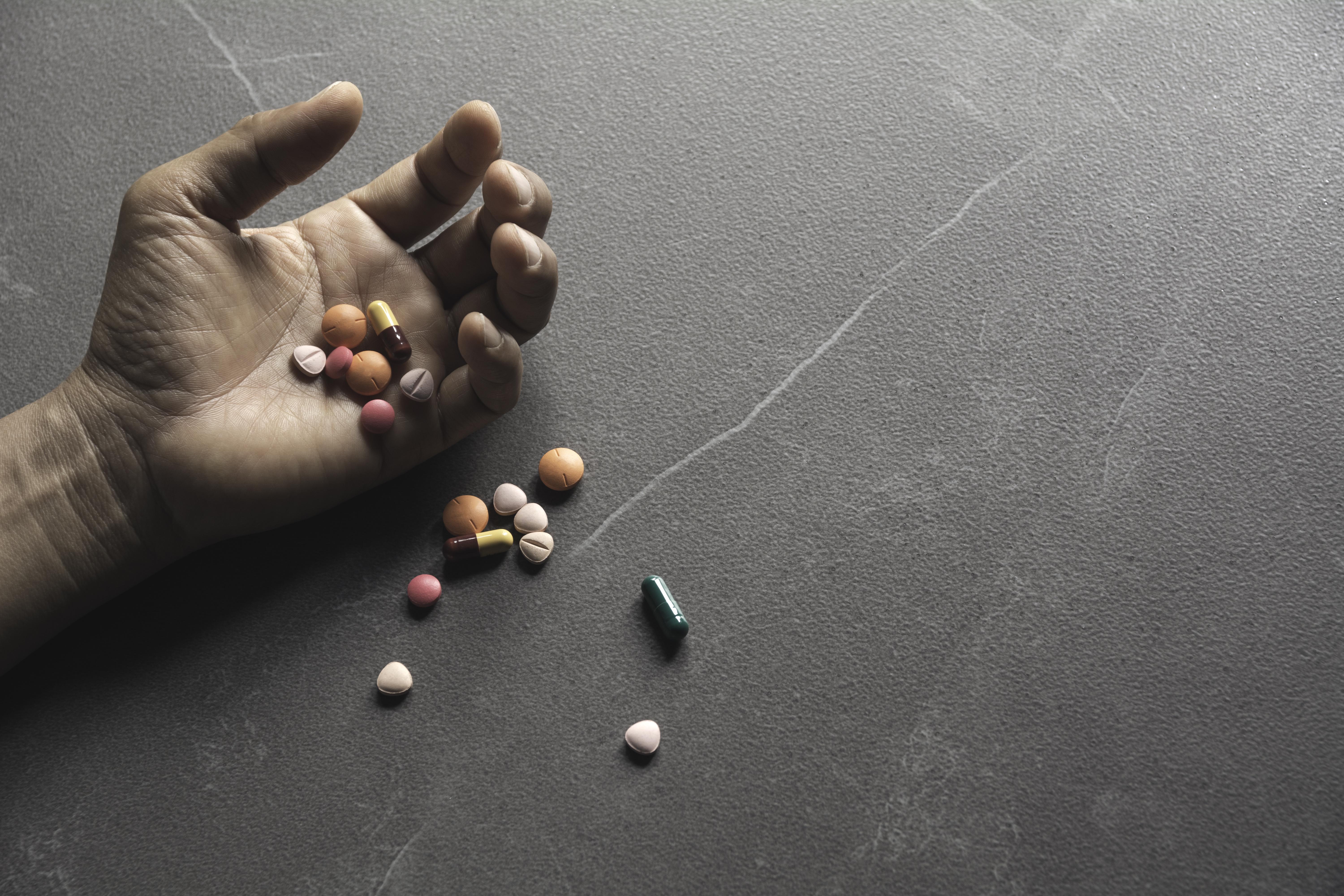

While most of these deaths are driven by external factors, interventions can still help prevent them.

Is death the final frontier? We ask scientists, philosophers, and spiritual leaders about life after death.

▸

14 min

—

with

The rites we give to the dead help us understand what it takes to go on living.

The heart of the religious ritual is mysticism, argues Brian Muraresku in “The Immortality Key.”

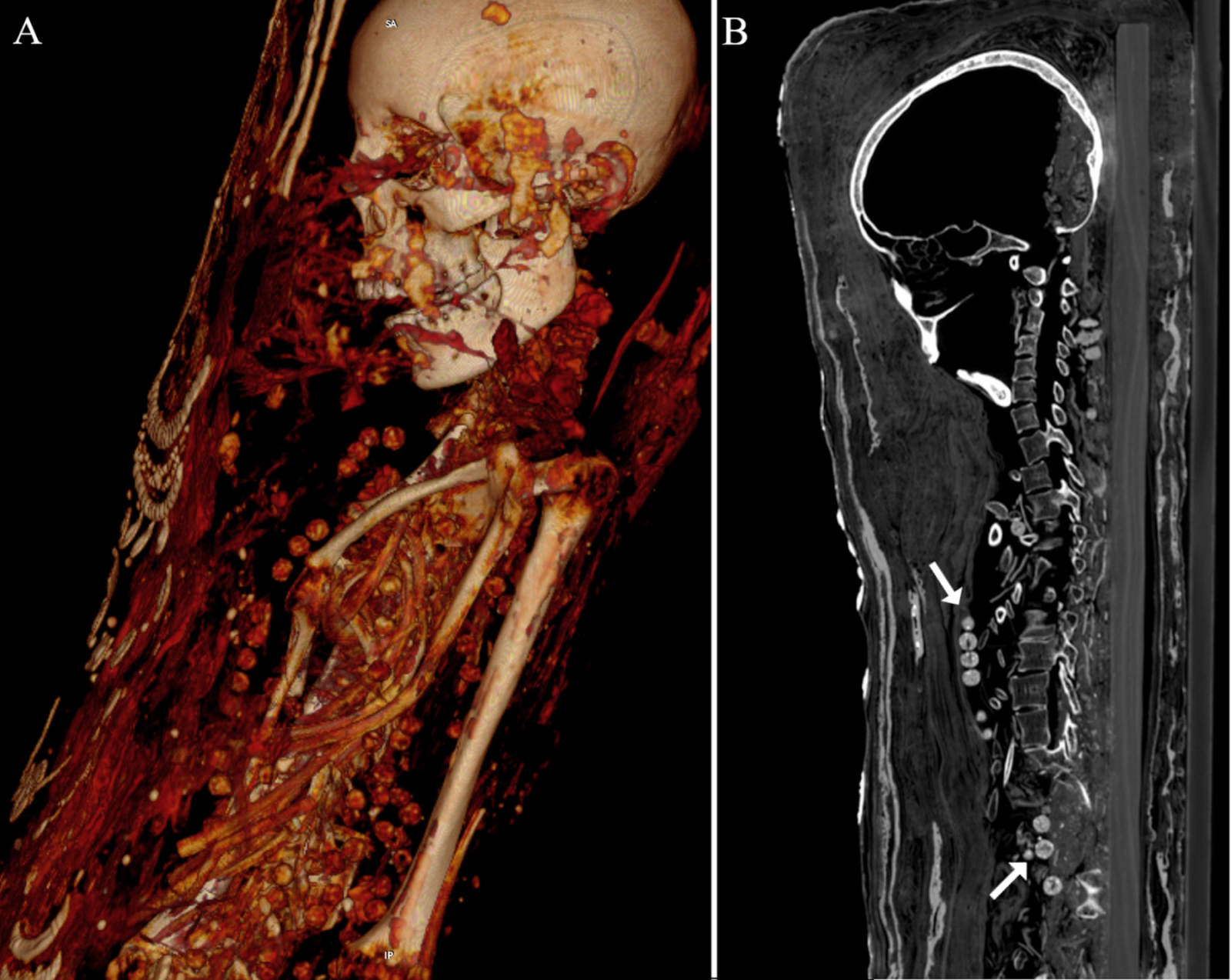

All the fun of opening up a mummy, without the fear of unleashing a plague.

Tea and coffee have known health benefits, but now we know they can work together.

This week, Big Think is partnering with Freethink to bring you amazing stories of the people and technologies that are shaping our future.

▸

6 min

—

with

From cryonics to time travel, here are some of the (highly speculative) methods that might someday be used to bring people back to life.

Remarkable ‘fan art’ commemorates 50th anniversary of legendary guitar player’s passing.

By projecting lifetime risk, an alarming new medical study centers the human lives that will be lost due to gun violence and drug addiction in the United States.

A man’s skeleton, found facedown with his hands bound, was unearthed near an ancient ceremonial circle during a high speed rail excavation project.

These Jurassic predators resorted to cannibalism when hit with hard times, according to a deliciously rare discovery.

As a doctor, I am reminded every day of the fragility of the human body, how closely mortality lurks just around the corner.

Is the cult of youth what we really want trailing us into the afterlife?

Being stuck at home is not as intense as being away from Earth, but there are ways to cope in either scenario.

▸

5 min

—

with

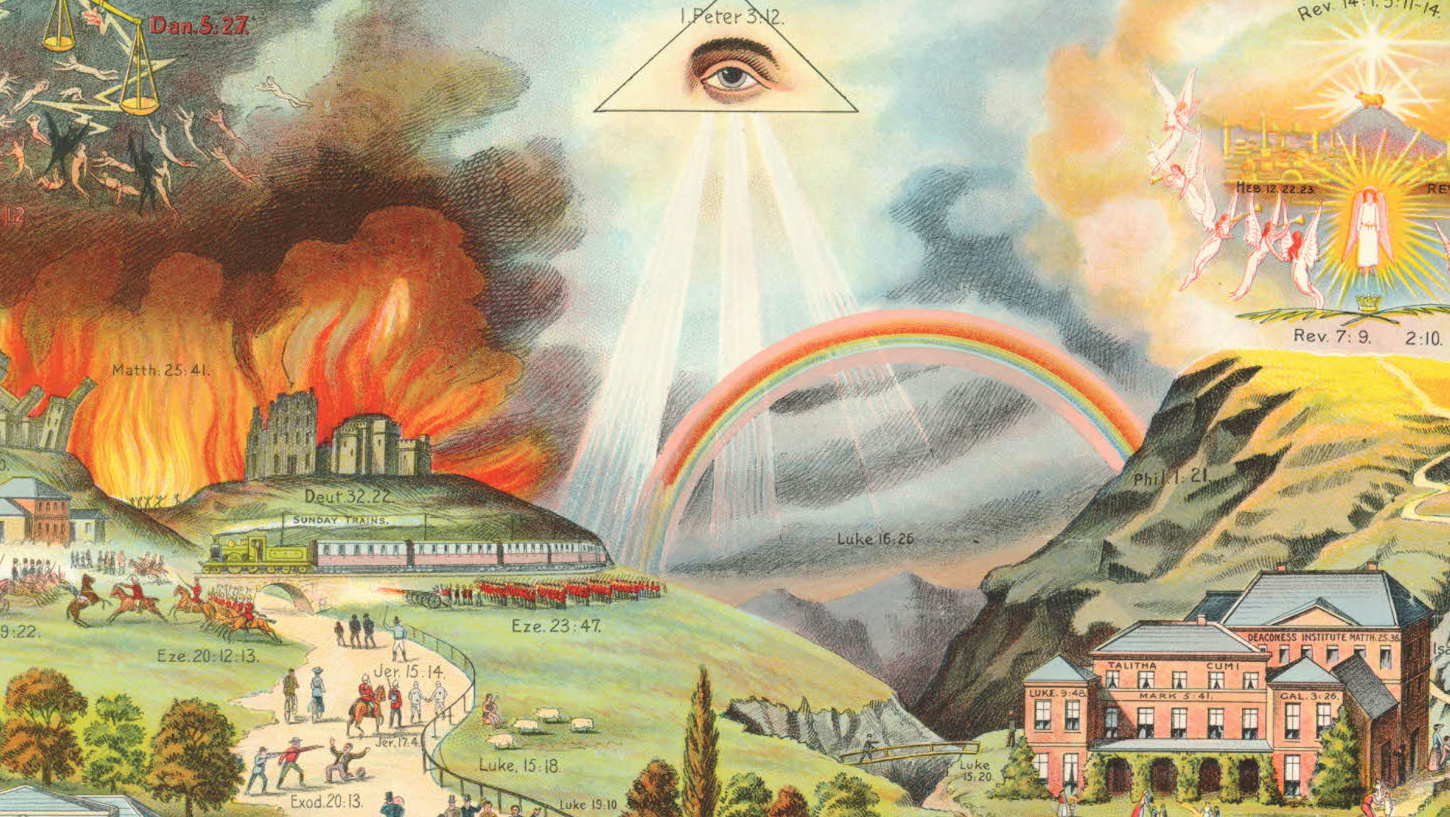

‘The Broad and Narrow Way’ helped 19th-century preachers explain the consequences of virtue and vice.

Philosopher Peter Singer broaches an uncomfortable truth about the Make-A-Wish Foundation and GoFundMe pages.

▸

2 min

—

with

Preventable deaths for all five leading mortality causes are “consistently higher” in rural communities.

Do you want Facebook or Google to control your legacy?