CRISPR

Forget AI. Gene editing is still our most powerful — and dangerous — technology.

▸

5 min

—

with

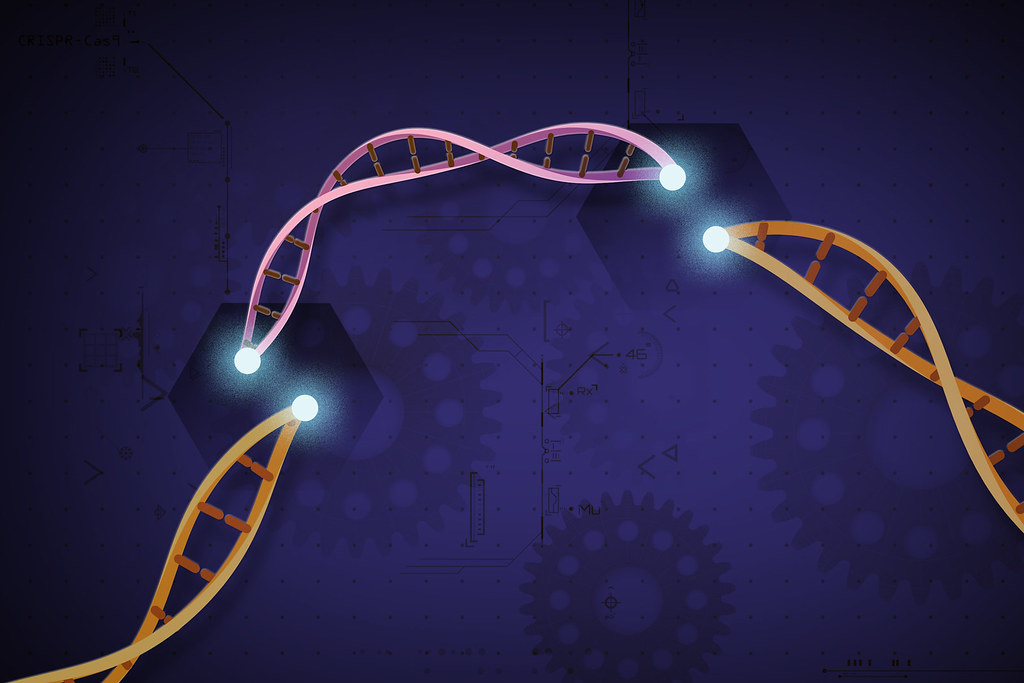

CRISPR’s gene drive can defy evolution. Here’s how, explained by Nobel Prize winner Jennifer Doudna.

▸

6 min

—

with

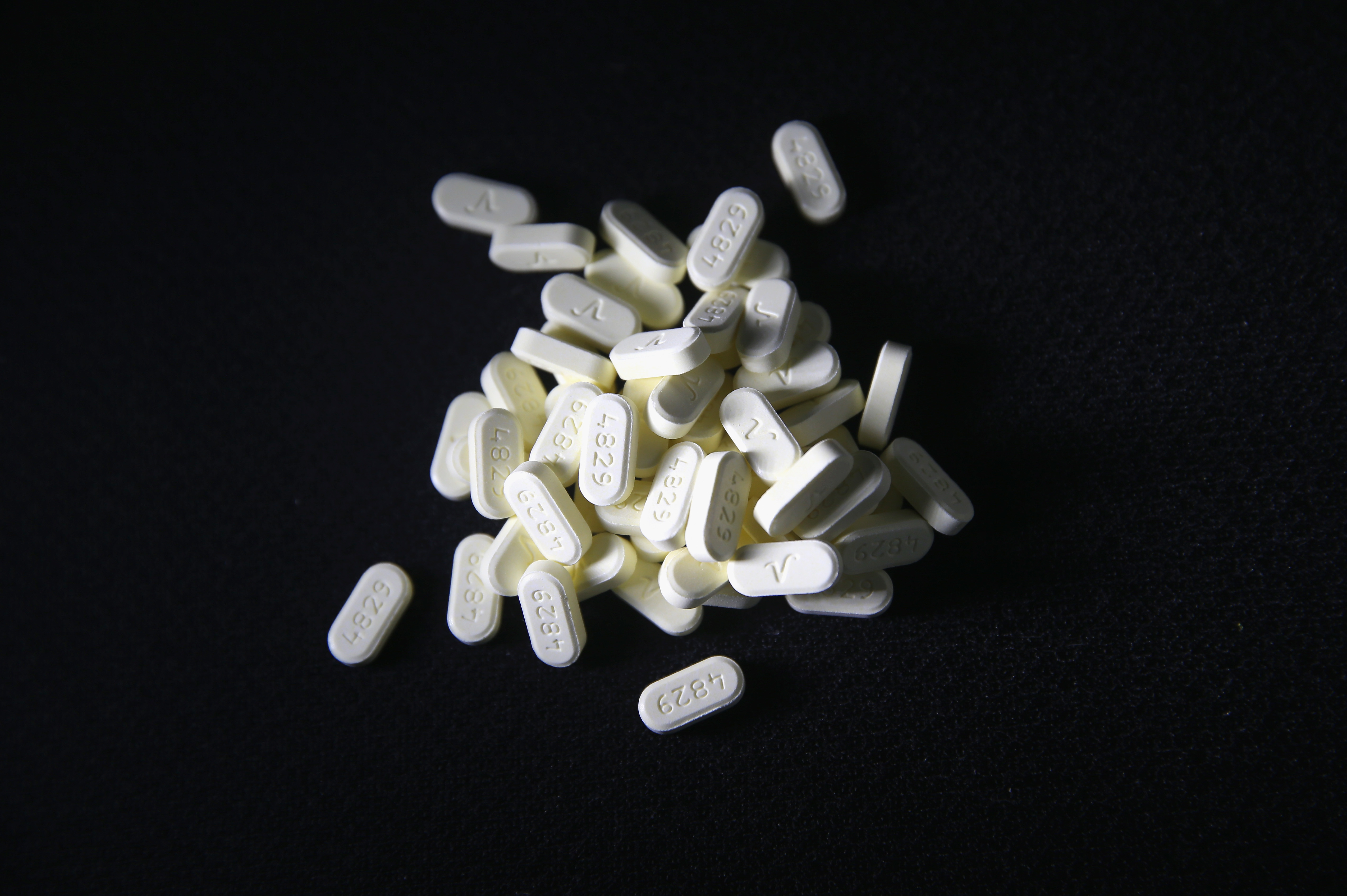

It marks a breakthrough in using gene editing to treat diseases.

She helped create CRISPR, a gene-editing technology that is changing the way we treat genetic diseases and even how we produce food.

In the near-term, gene editing is not likely to be useful. Even in the long-term, it may not be very practical.

The potential of CRISPR technology is incredible, but the threats are too serious to ignore.

▸

14 min

—

with

How would the ability to genetically customize children change society? Sci-fi author Eugene Clark explores the future on our horizon in Volume I of the “Genetic Pressure” series.

Researchers from the University of Toronto published a new map of cancer cells’ genetic defenses against treatment.

Is CRISPR the solution?

New research shows how Americans feel about genetic engineering, human enhancement and automation.

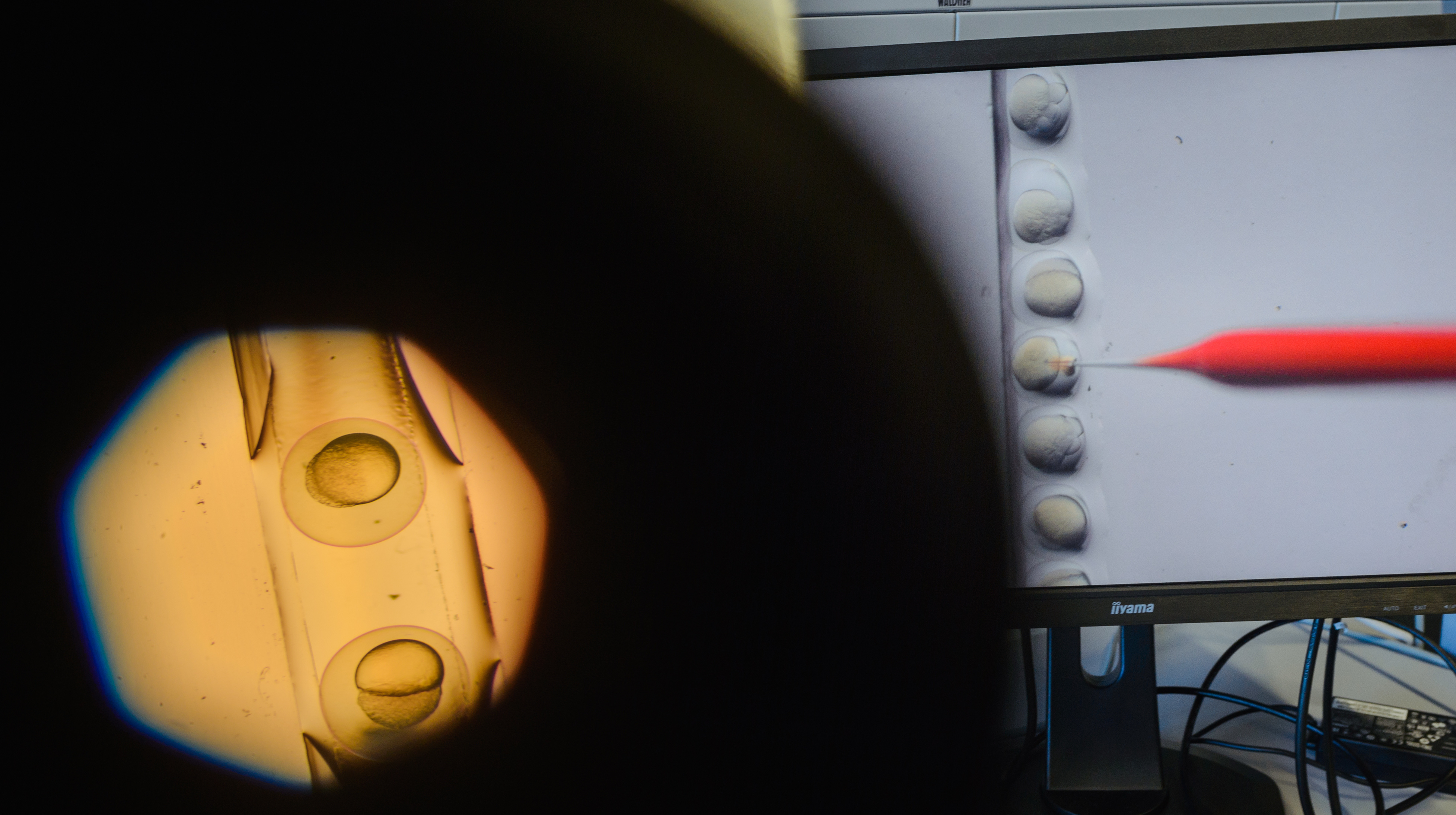

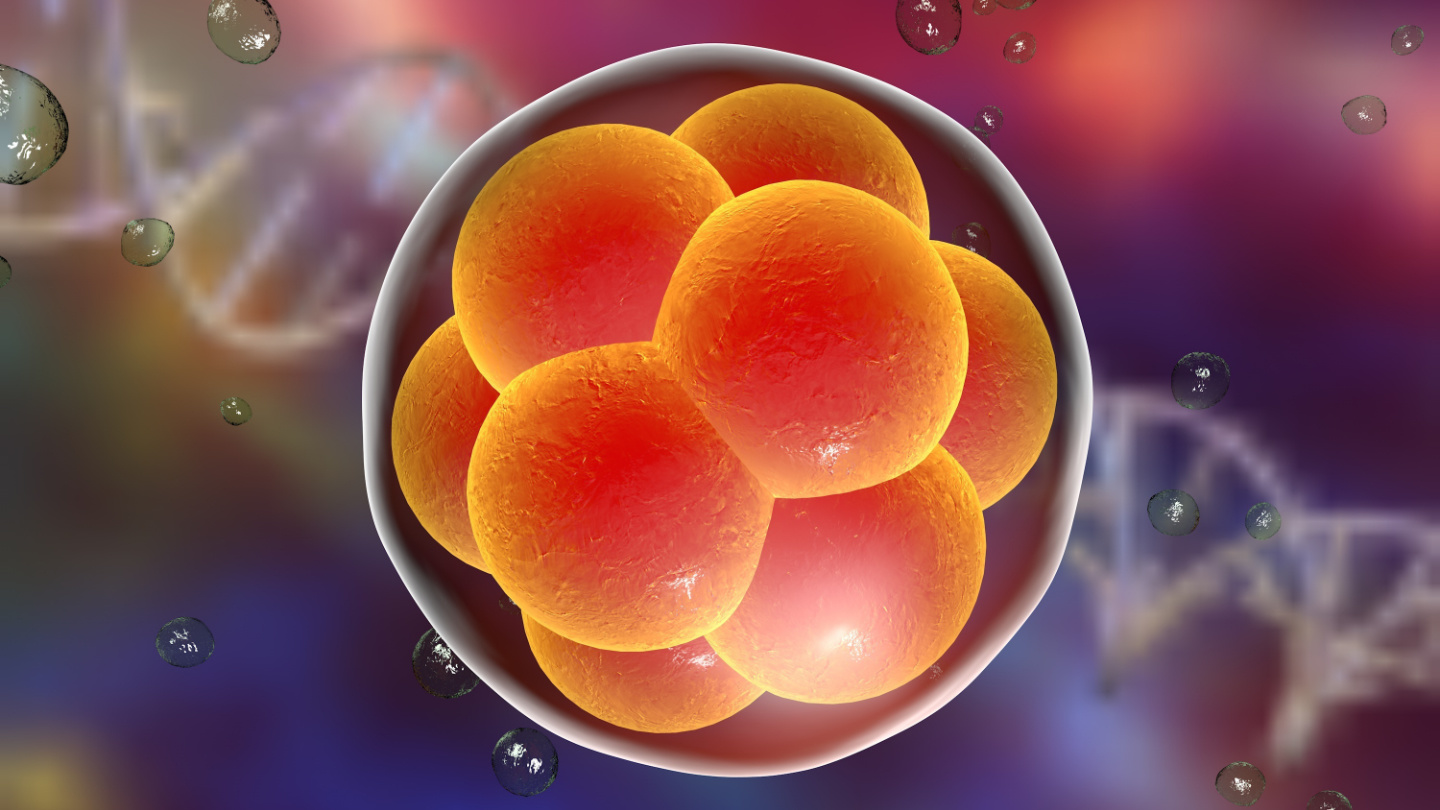

A punishment is handed down for performing shocking research on human embryos.

Experts are saying it’s a “huge step forward for synthetic biology.”

A transformational tool for the future of the world.

Do scientists know enough about gene editing to move forward with human trials?

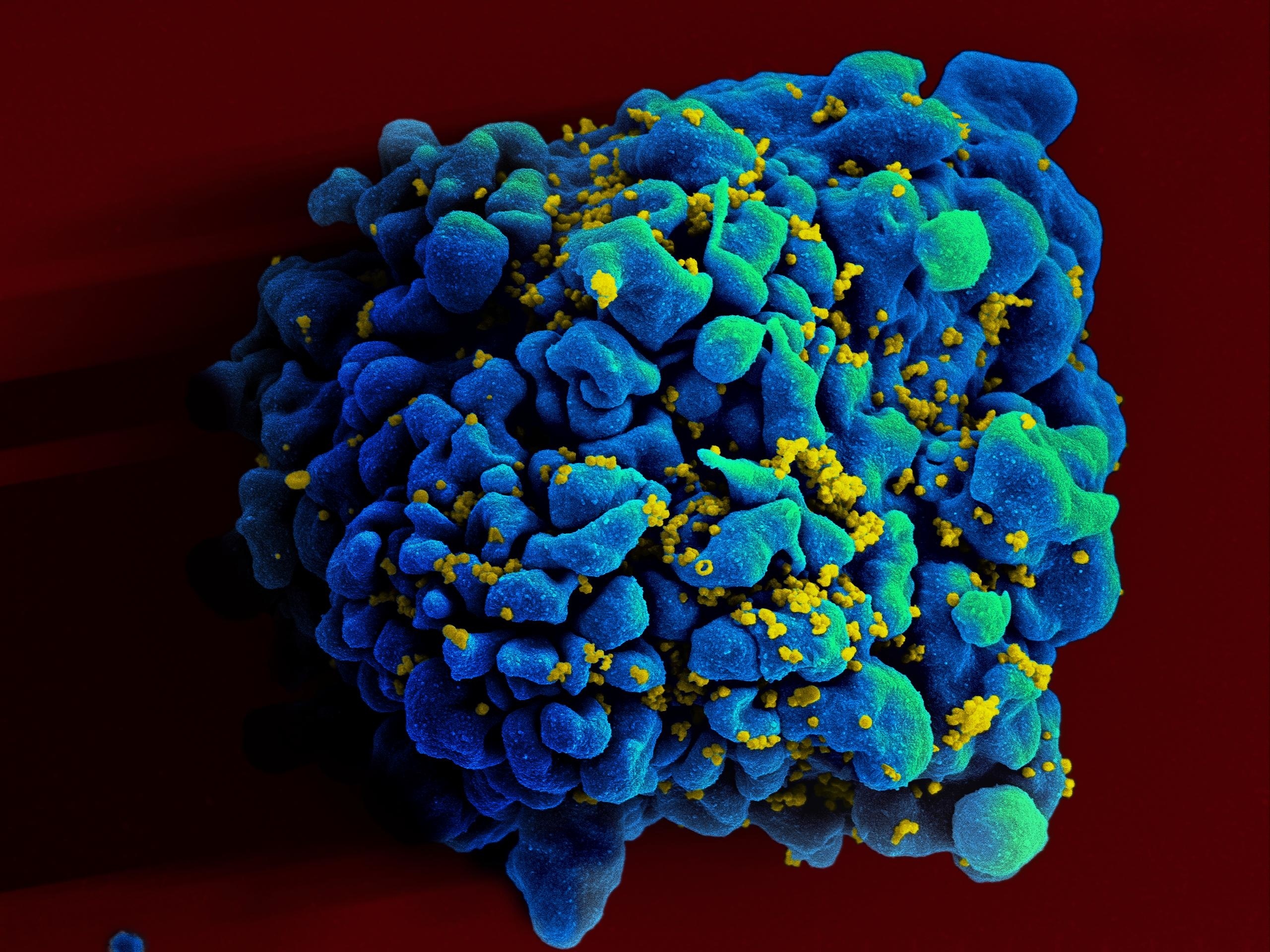

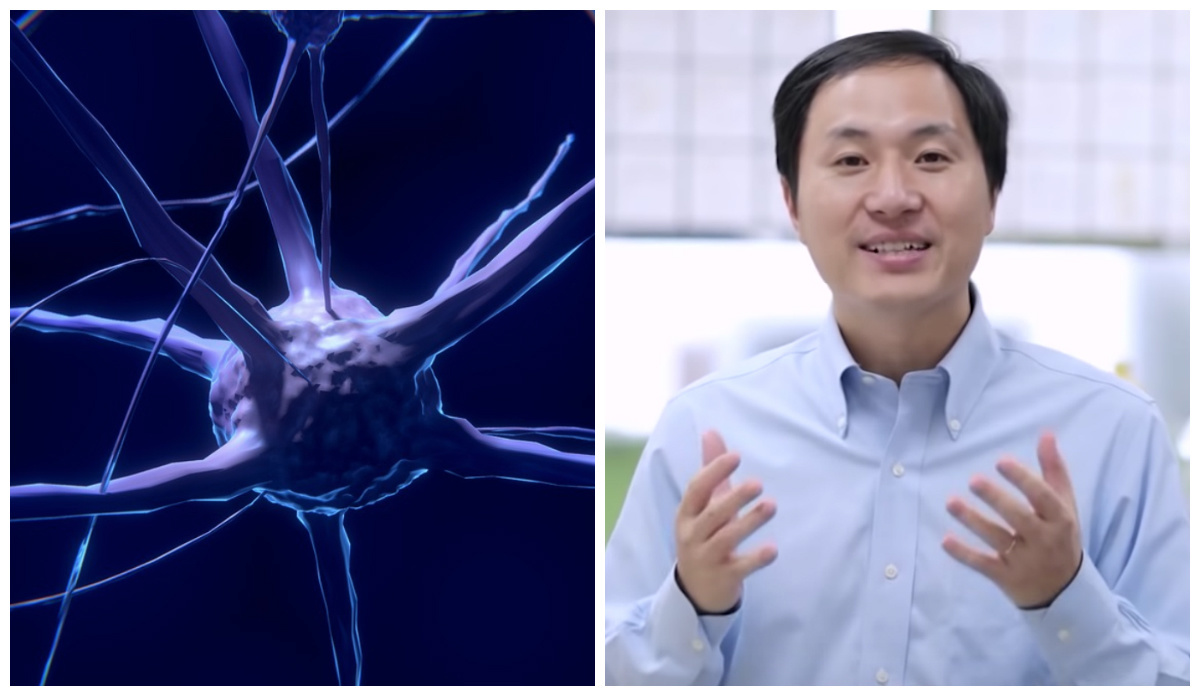

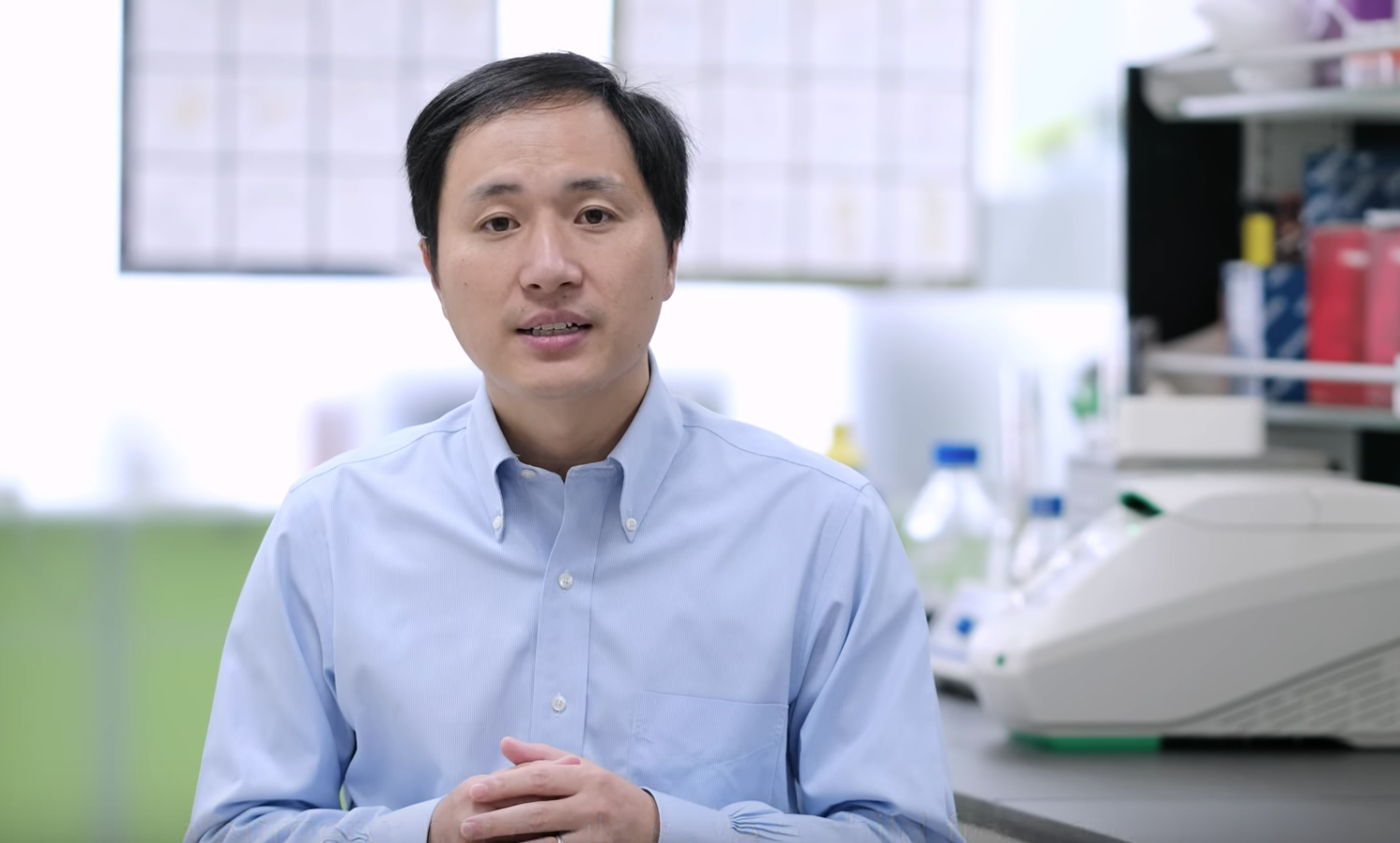

Chinese scientist He Jiankui edited the genes of two babies to be resistant to HIV, provoking outrage. Now, a new genetic analysis shows why this was reckless.

Synthetic biology is changing the way the planet works.

New research solves a long-standing puzzle.

The brains of two genetically edited babies born last year in China might have enhanced memory and cognition, but that doesn’t mean the scientific community is pleased.

The controversial scientist He Jiankui is currently missing after causing major controversy in late November.

Big Think expert Dr. Jennifer Doudna, a professor at UC Berkeley and co-inventor of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology, issued a statement responding to a scientist’s recent claim that he helped create the world’s first genetically edited babies.

Scientists in Japan have genetically modified chickens to lay eggs containing an extremely valuable protein that helps treat cancer, hepatitis and multiple sclerosis in humans. The cost of one of […]

Granted, genetic manipulation has been a dream for decades. Here’s what is different now.

We can “read” genes with ease now, but still can’t say what most of them “mean.” To show why we need clearer “causology” and fitter metaphors, let’s scrutinize cars and their parts like we do bodies and genes.

Researchers succeed in deleting key genes from ants, significantly modifying their behavior.

U.S. scientists have successfully repaired DNA in a human embryo for the first time.

Has CRISPR co-creator Jennifer Doudna invented the Pandora’s Box of genetic engineering, or can CRISPR be used for the forces of good?

▸

7 min

—

with

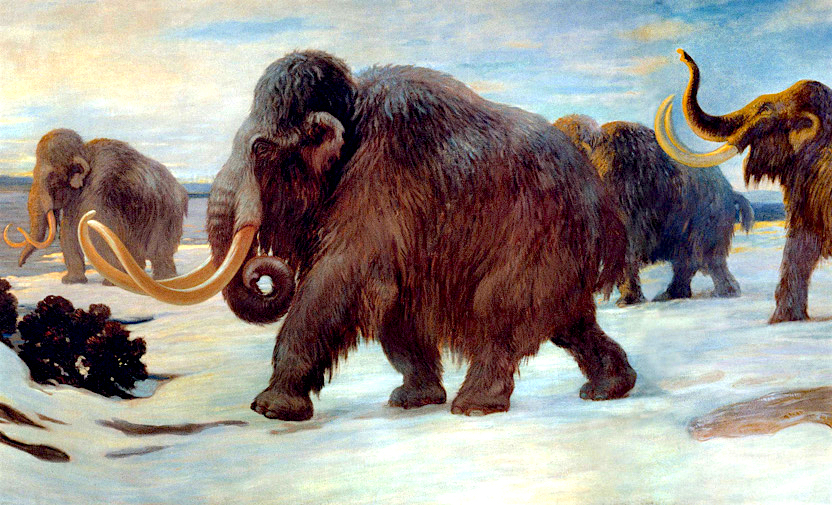

Harvard scientists say they are two years away from creating a hybrid embryo with mammoth traits.

Creating a race of super soldiers is off the table, too.

Has technology advanced enough that we could stitch together body parts and reanimate the dead? Bill Nye one-ups that old-school Frankenstein vision with newer (and cooler) scientific possibilities.

▸

5 min

—

with