youtube.com

Most of it was eaten by Earth’s mantle, but scraped-off bits survive in the Alps and other mountain ranges.

As Game of Thrones ends, a revealing resolution to its perplexing geography.

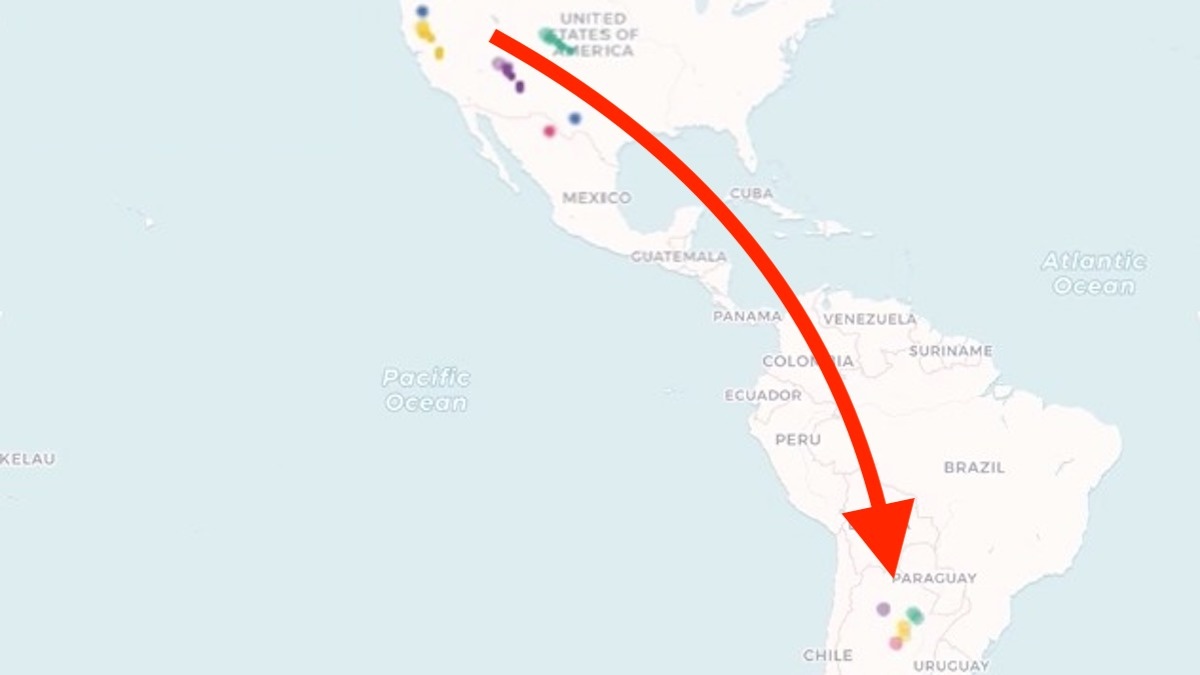

Tracking project establishes northern Argentina is wintering ground of Swainson’s hawks

No, the Syrian civil war is not over. But it might be soon. Time for a recap.

▸

with

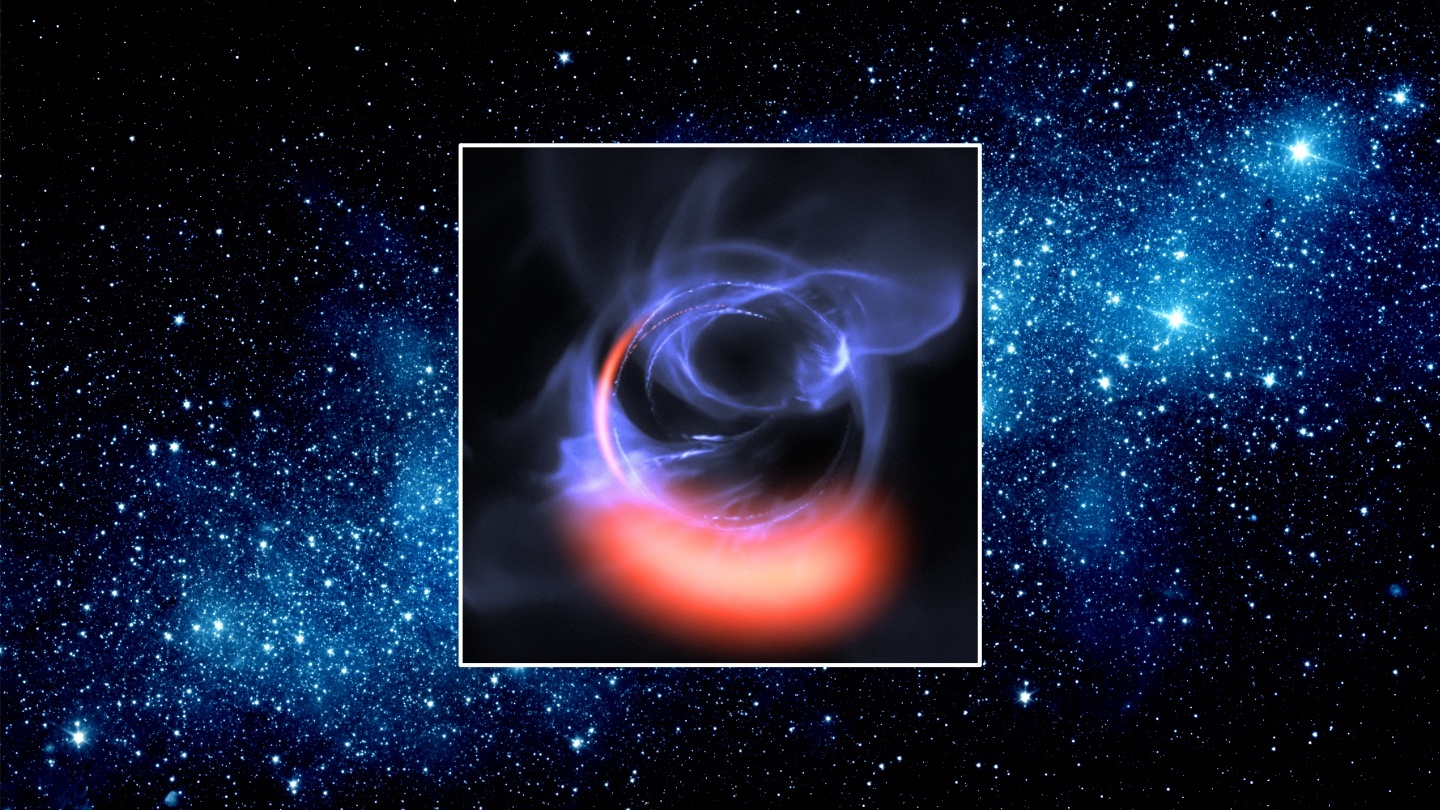

A young star and a belt of gasses give the game away.

This meteorite is the oldest known volcanic rock in the solar system, dated at 4,565,000,000 years old.

▸

with

Take one long stroll, four times a week.

West delivered an impassioned speech on American industry and transport, even pitching a high-tech plane to Apple.

▸

with

Scientists at Stanford Medicine recently observed that some mice recovered from strokes better than others, leading them to wonder whether or not they could find evidence that specific genes played […]

A man paralyzed from the waist down was able to voluntarily control and move his legs with the help of an electrical implant in his spine.

Quarantines are worth the trouble to keep the next pandemic at bay but they need to be applied intelligently.