united states

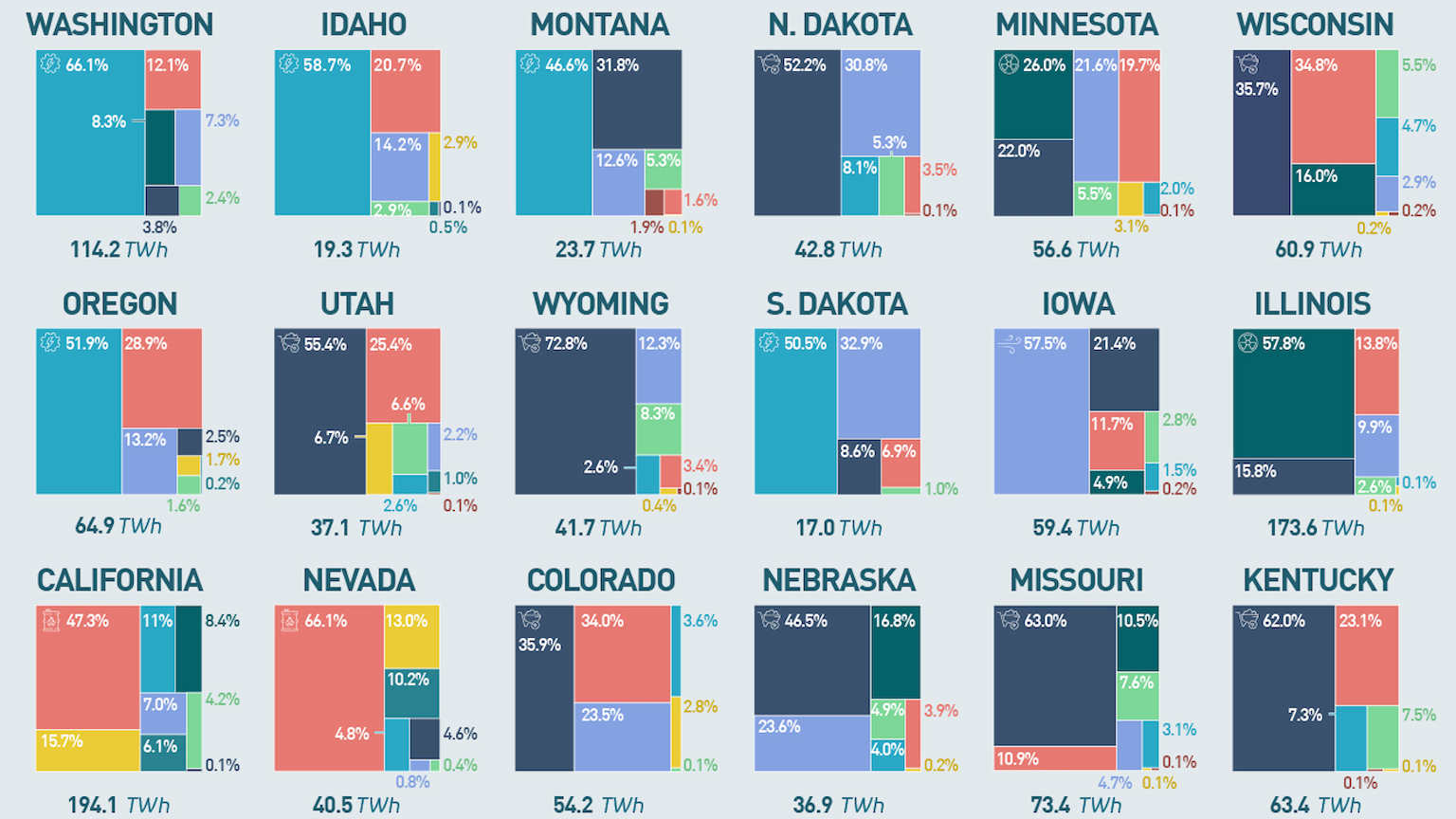

U.S. states vary radically in terms of electricity generation. Vermont is the cleanest, while Delaware is the dirtiest.

Hindsight is 20/20, particularly when you have had 20 years to think about what happened.

Technology designed to listen for atomic bombs can also hear tornadoes.

Paradoxically, we lose wars because the world is peaceful and the U.S. is powerful.

The questions about which massive structures to build, and where, are actually very hard to answer. Infrastructure is always about the future: It takes years to construct, and lasts for years beyond that.

Opponents of 19th-century American imperialism were not above body-shaming the personification of the U.S. government.

A new government report describes 144 sightings of unidentified aerial phenomena.

By slowing down aging, we could reap trillions of dollars in economic benefits.

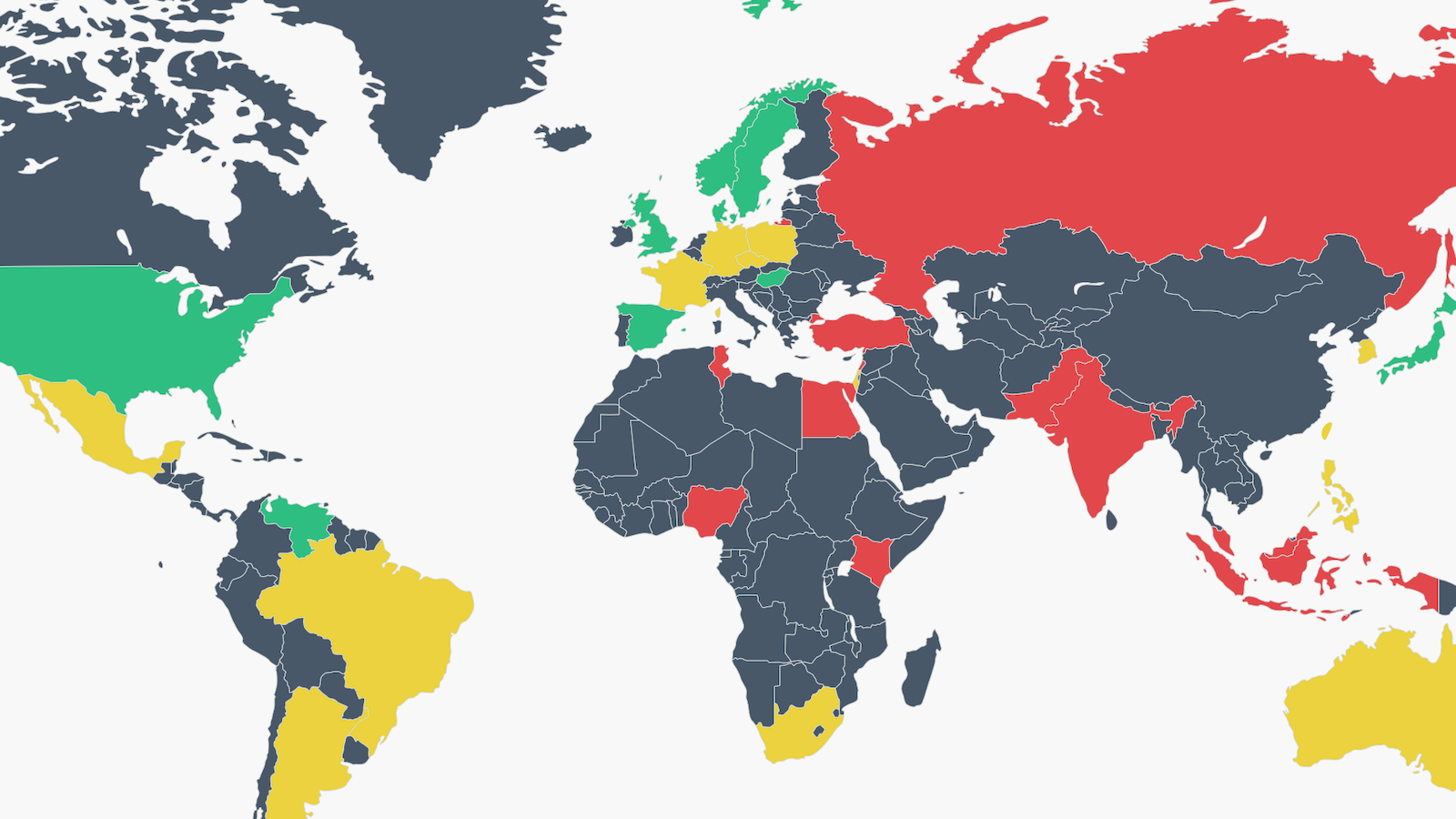

In some countries, people want more freedom of speech. In others, they feel that there is too much.

Most schools use a semester system, but a new study suggests that they should switch to quarters.

At least 222 typefaces are named after places in the U.S. — and there’s still room for more.

A brief passage from a recent UN report describes what could be the first-known case of an autonomous weapon, powered by artificial intelligence, killing in the battlefield.

A cartogram makes it easy to compare regional and national GDPs at a glance.

We have pipelines for oil and natural gas. Why not water?

Political partisanship might be a treatable condition.

A new study suggests that private prisons hold prisoners for a longer period of time, wasting the cost savings that private prisons are supposed to provide over public ones.

American universities used to be small centers of rote learning, but three big ideas turned them into intellectual powerhouses.

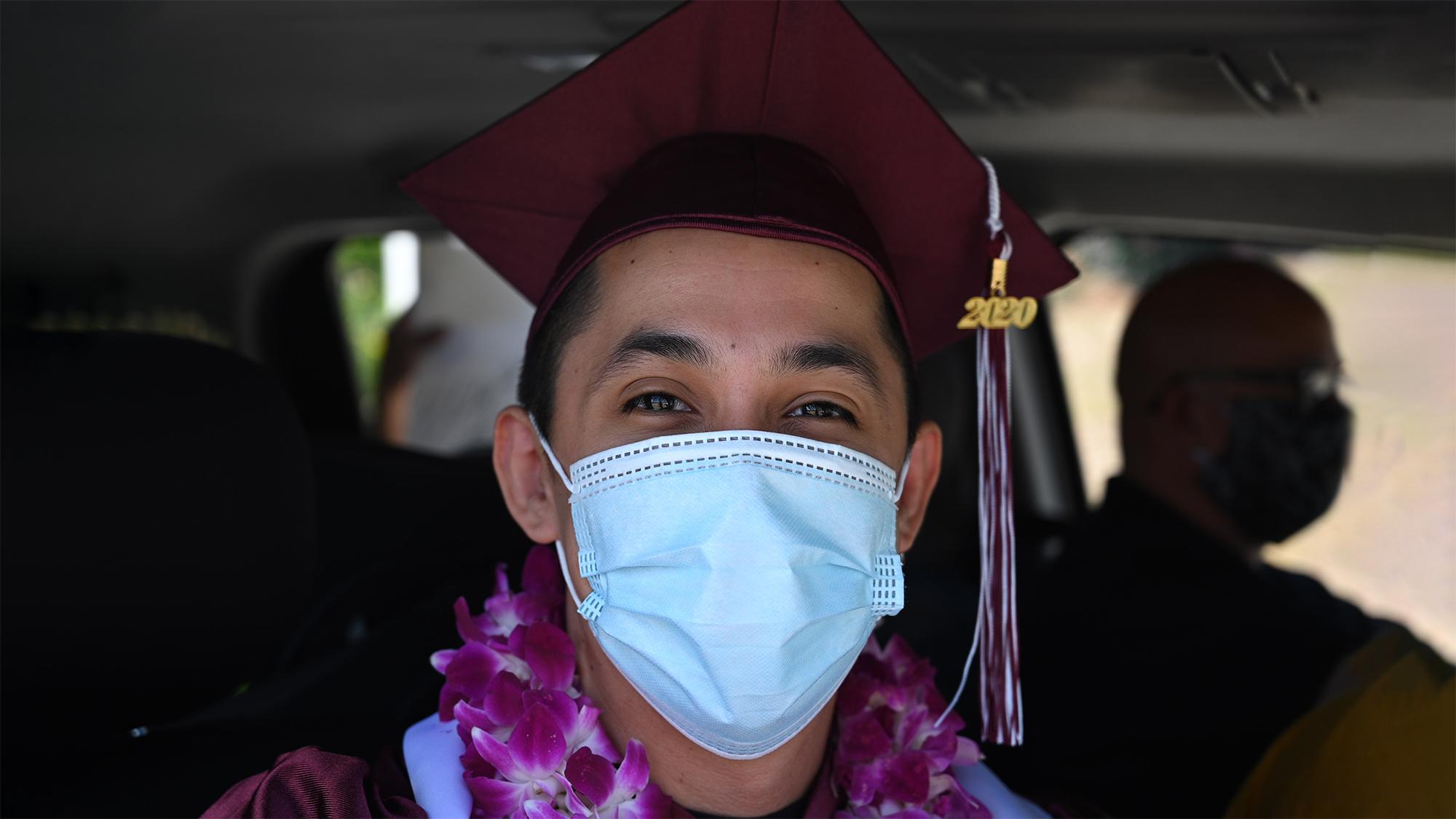

Millions of doses of Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine could be distributed as early as this week.

Surprising as it may seem, we are all very good at denial. Negation, however, is a different phenomena.

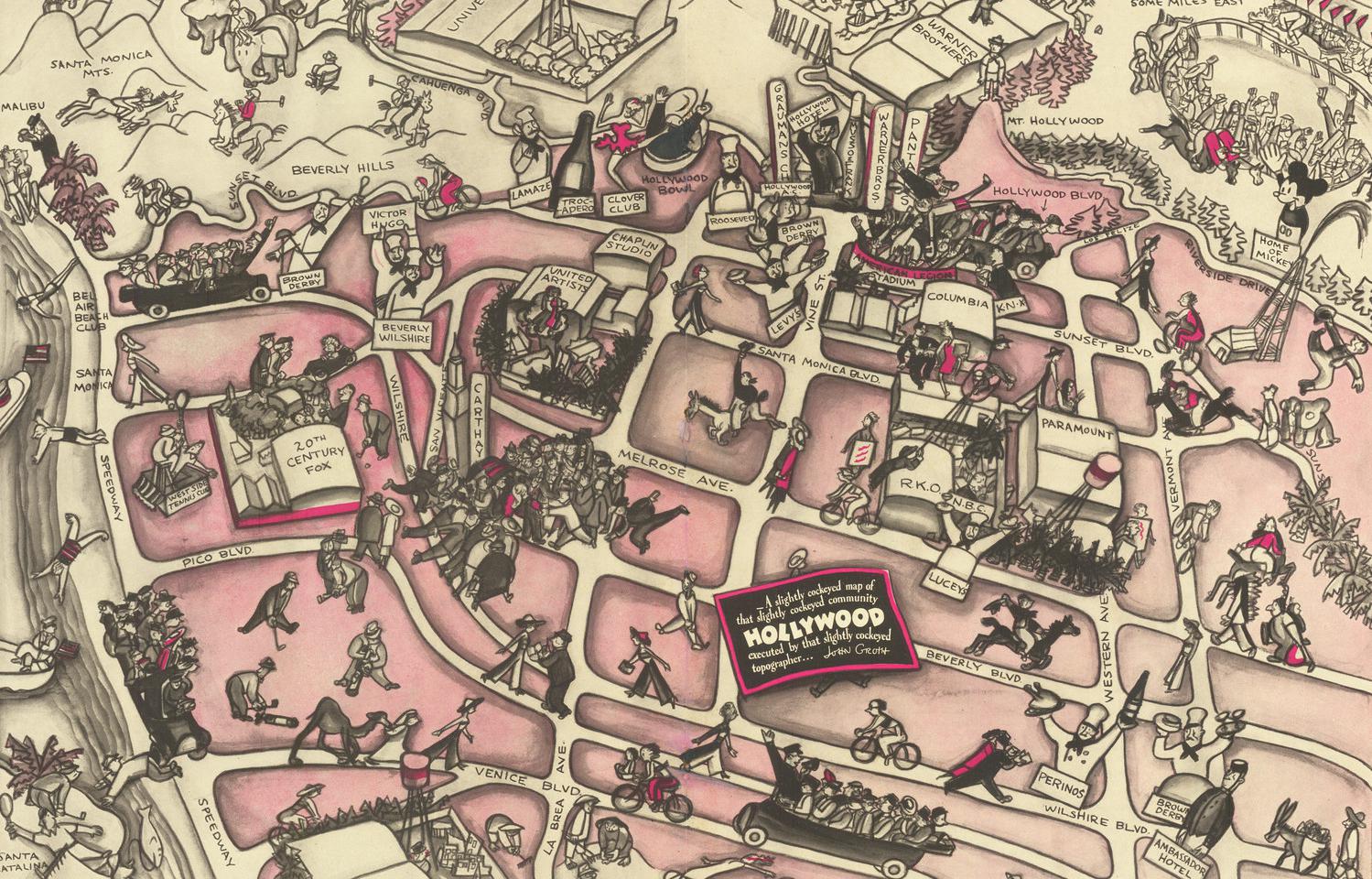

Legendary cartoonist John Groth’s pictorial map captures LA’s film factories in their Golden Age.

The opening lines of Smartmatic’s $2.7 billion lawsuit against Fox News lay bare the culture of denial in the US.

7 scholars and legal experts dissect what you can and can’t say in America.

▸

22 min

—

with

Most people believe you can win an argument with facts – but when “facts” are so often subject to doubt, are personal experiences trusted more?

The idea behind the law was simple: make it more difficult for online sex traffickers to find victims.

The long-term lessons America learns from the coronavirus pandemic will spell life or death.

▸

3 min

—

with

For centuries, universities have advanced humanity toward truth. Professor Jonathan Haidt speaks to why college campuses are suddenly heading in the opposite direction.

A new survey shows who believes what and how it differs from what Americans believe as a whole.

Research from MIT’s School Effectiveness & Inequality Initiative found making college more affordable cut dropout rates and boosted degree attainment.

The federal government and private insurers greatly increased Americans’ telehealth access during the pandemic. Will these changes be permanent?

For too many people, a poor education is a destructive barrier in their lives—a source of limitation rather than opportunity. Together, we can change this.