population

Reality is more distorted than we think.

▸

with

Birthrates are cyclical and have gone up and down throughout history.

Too few babies — not overpopulation — is likely to be a major problem this century.

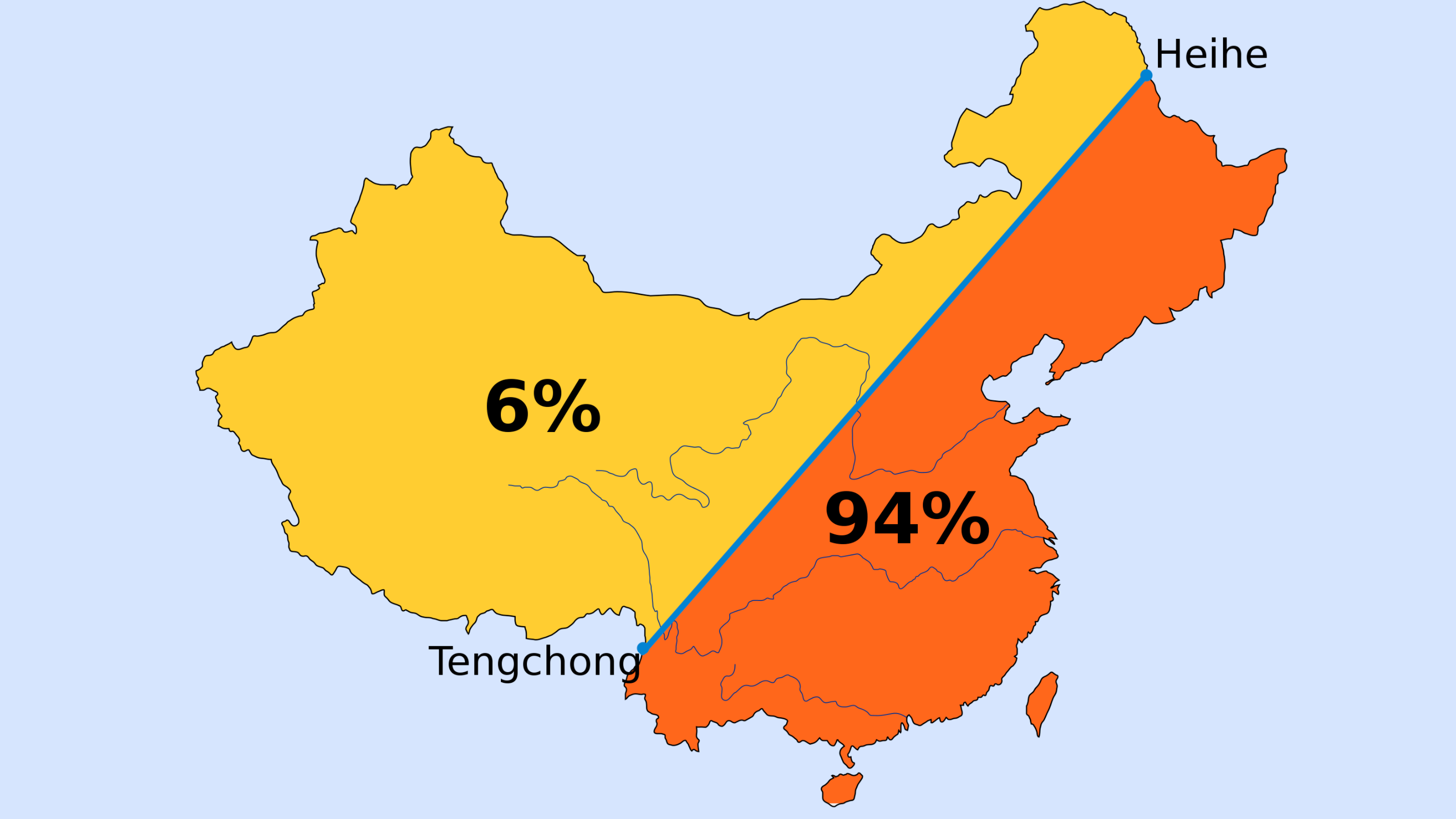

First drawn in 1935, Hu Line illustrates persistent demographic split – how Beijing deals with it will determine the country’s future.

What would happen if you tripled the US population? Matthew Yglesias and moderator Charles Duhigg explore the idea on Big Think Live.

▸

with

Virtual reality is more than a trick. It’s a solution to big problems.

▸

11 min

—

with

Having lots of kids is great for the success of the species. But there’s a hitch.

Pew Research Center data shows that most people think diversity improves lives in their countries.

The lessons we’ve learned here on Earth will affect how we govern a new world.

▸

4 min

—

with

Why did the dinosaurs go extinct? Because they didn’t have a space program.

▸

4 min

—

with

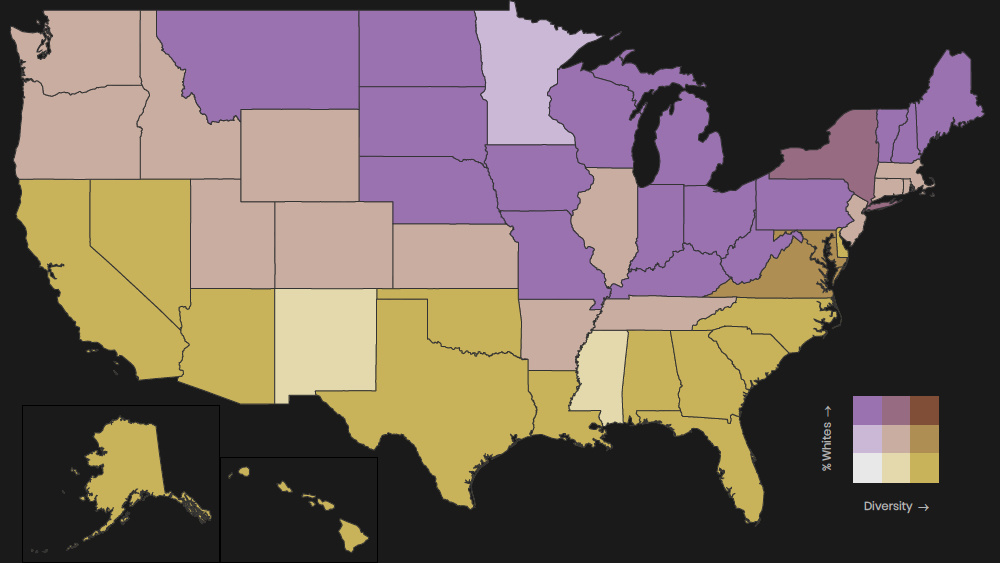

The Data Atlas of the World specialises in simple yet revealing maps of the world.

The associations of civil society give us freedom to find systems that meet our needs.

▸

8 min

—

with

How will the current challenges to the global economy pressure it to change?

▸

4 min

—

with

The welfare state is broken. UBI is the smarter, more effective option.

▸

4 min

—

with

Economics professor Stephen M. Miller shares his insights in this exclusive interview.

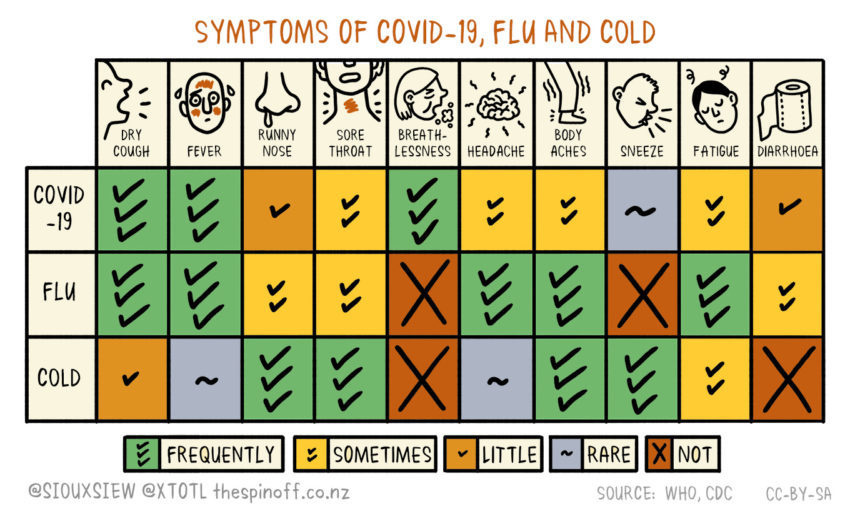

What symptoms to watch for, how to get tested, what to do if you’re sick, and when to go to the doctor.

Cities of the future won’t just be incredibly populated, they’ll also be smarter than ever.

▸

3 min

—

with

School diversity is less widespread in central and northern states

Around 9 percent of the U.S. population believe the Pizzagate theory is true.

Are tiny homes just a trend for wealthy minimalists or an economic necessity for the growing poor?

A new study challenges international life expectancies.

Without a country to belong to, many of these people lack some of the most fundamental rights.

A team of Japanese researchers comes across a remarkably simple trick.

Russia urges villagers to leave nuclear fallout area and then tells them to come back.

A new study finds that factors influencing where you’re born continue to affect your earnings throughout life.

At 18 percent of the population, Hispanics account for 67.2 percent of U.S. net homeownership gains.

The Doomsday clock has never been closer to midnight.

The Flynn effect shows people have gotten smarter, but some research claims those IQ gains are regressing. Can both be right?