plastic

Masks are great, but what happens when we try to throw out a billion masks at once?

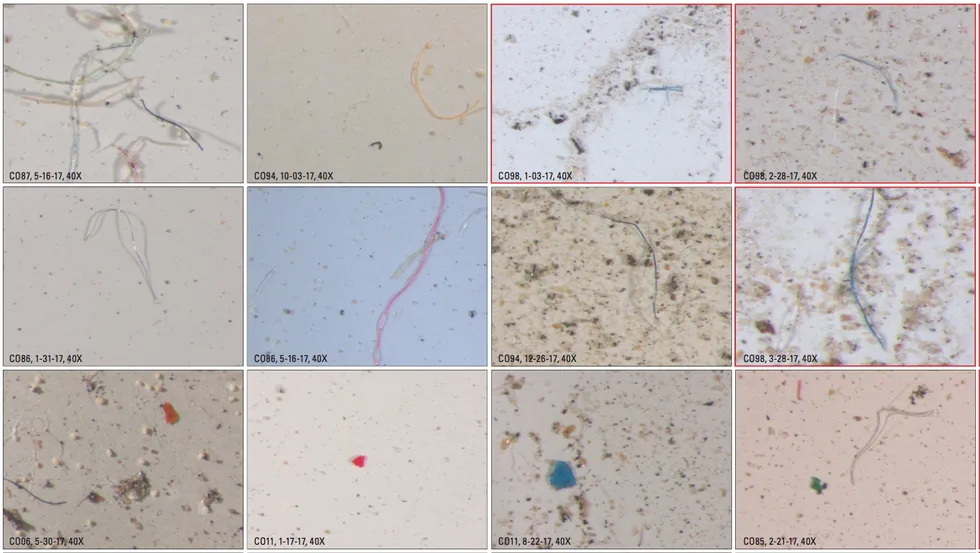

More evidence that we’re drowning in microplastic particles.

The researchers hope to develop a no-trace plastic to curtail marine pollution and ghost fishing.

A new study says that it could be centuries before millions of the classic toys submerged in the Earth’s seas disintegrate.

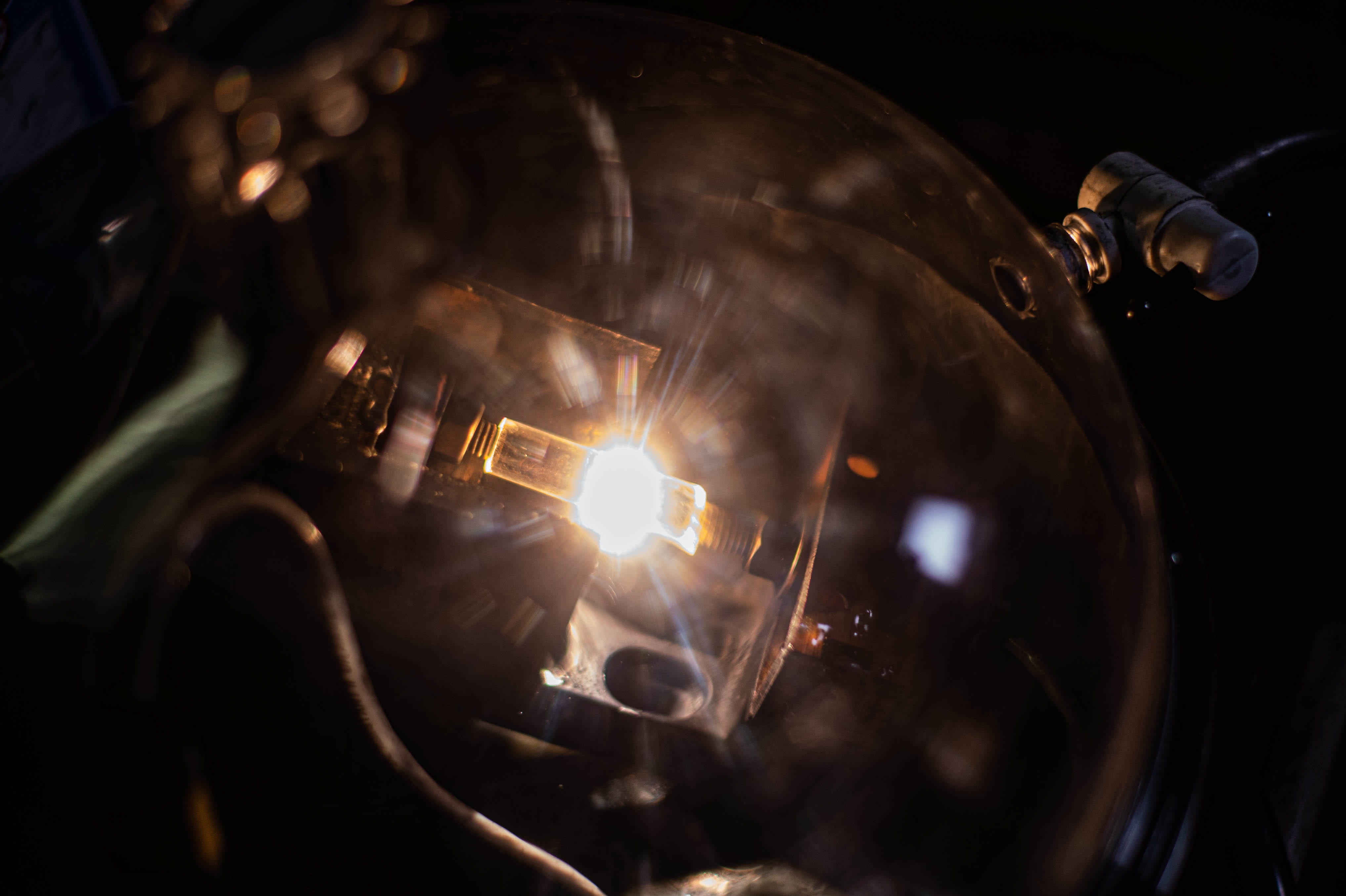

Graphene is insanely useful, but very difficult to produce — until now.

A new method of measuring human exposure to the potentially toxic chemical calls into question regulatory policy.

When these particles are eaten by earthworms, the results are not good.

Those silky tea bags might be releasing plastics into your digestive system.

Bio-plastics could prove to be a suitable alternative to single-use plastics.

An ecological silver bullet is missing the target altogether.

The startling discovery comes from researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey.

“Our findings are not good news,” says Brendan Godley, of the University of Exeter.

The study was small: 8 people from 8 different countries. But the findings have alarmed scientists.

China’s expanding middle class is changing the world. The results are a global recycling dilemma.

Scientists find a surprising way to biodegrade plastic at an impressively fast rate.