manufacturing

How one startup plans to use “death rays” for good instead of evil.

The long-term lessons America learns from the coronavirus pandemic will spell life or death.

▸

3 min

—

with

Humans churn out about 30 gigatons (30,000,000,000 tons) of material every year.

Ready to see the future? Nanotronics CEO Matthew Putman talks innovation and the solutions that are within reach.

▸

with

Frequent shopping for single items adds to our carbon footprint.

The best and worst of yesterday has created the economy of today.

▸

7 min

—

with

The rules have changed, and so have we.

▸

4 min

—

with

In a recent interview, a former Boeing quality manager cited numerous safety concerns in the 787 Dreamliner.

Recent years have seen countries across the African continent investing deep into the tech industry. Rwanda is angling to get ahead of the pack.

Is the pessimism about jobs totally unwarented?

Even if automation makes human trafficking economically inefficient, that alone won’t end this unethical practice.

It turns out light can not only be twisted, but at different speeds.

An investigation finds the cause of failed NASA launches and $700 million in losses.

The technology is poised to change how many companies operate.

▸

8 min

—

with

Co-ops are more pervasive than you think. They just suffer from a marketing problem.

Japan looks to replace China as the primary source of critical metals

Mercantilism, the oldest thing in economics, is back in a big way.

Be glad your name isn’t attached to any of these bad ideas.

Inconceivable wealth. And a few lessons in how not to get rich, too.

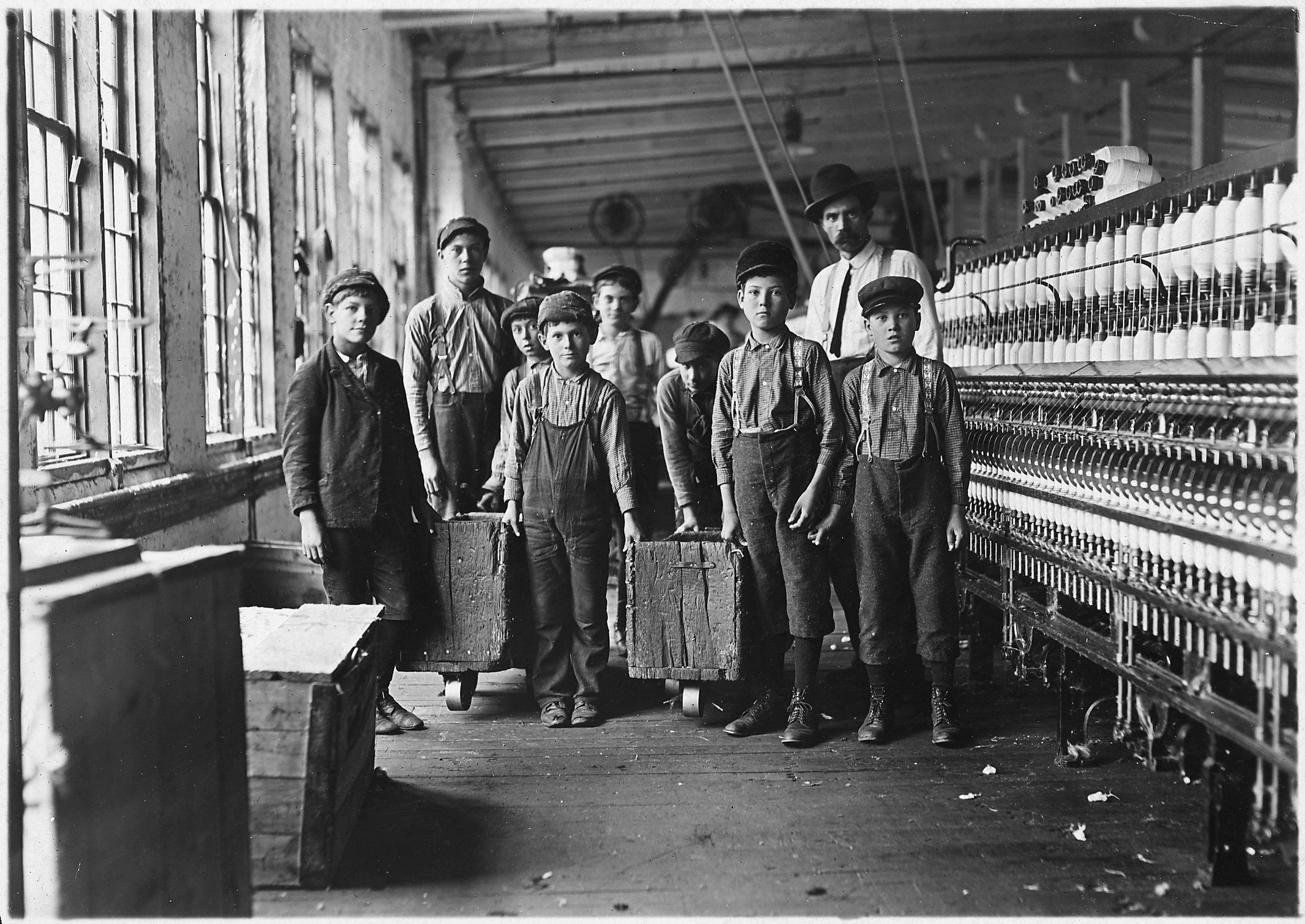

The Industrial Revolution brought along the second agricultural revolution, the unthinkable transformations of entire ecosystems, the collapse of the family and community, and the ethics of consumerism.

China’s expanding middle class is changing the world. The results are a global recycling dilemma.

Everything is cheap and nobody has jobs. Welcome to the future. President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas fills us in on how we got here.

▸

10 min

—

with

A new report shows the marijuana industry is poised to have a major economic impact.

Bill Nye casts his mind to the future to give us a picture of how the descendants of our current 3D printing technology will change our ways and our world.

▸

4 min

—

with