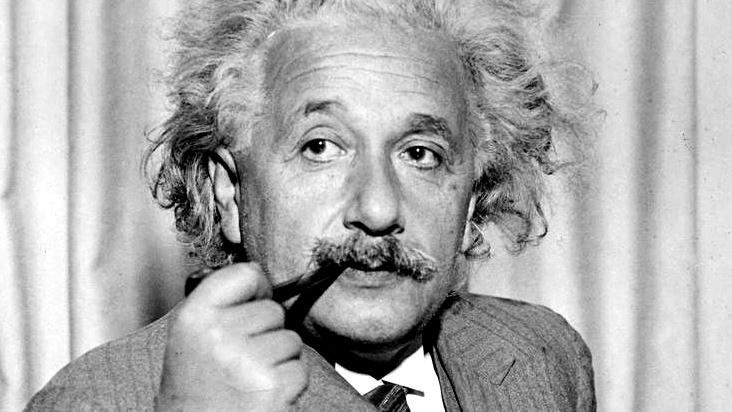

einstein

Is the physical universe independent from us, or is it created by our minds, as suggested by scientist Robert Lanza?

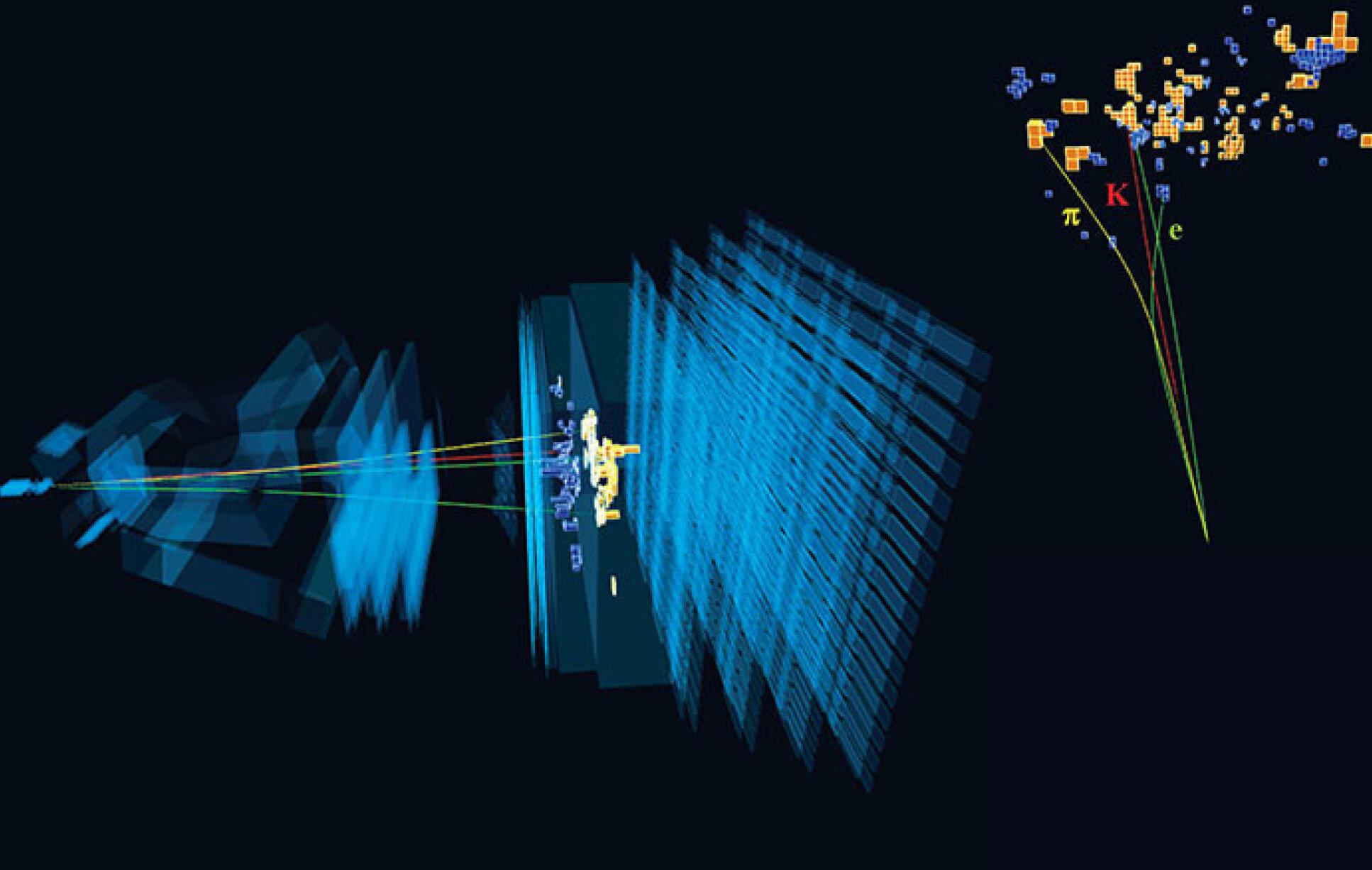

Results from an experiment using the Large Hadron Collider challenges the accepted model of physics.

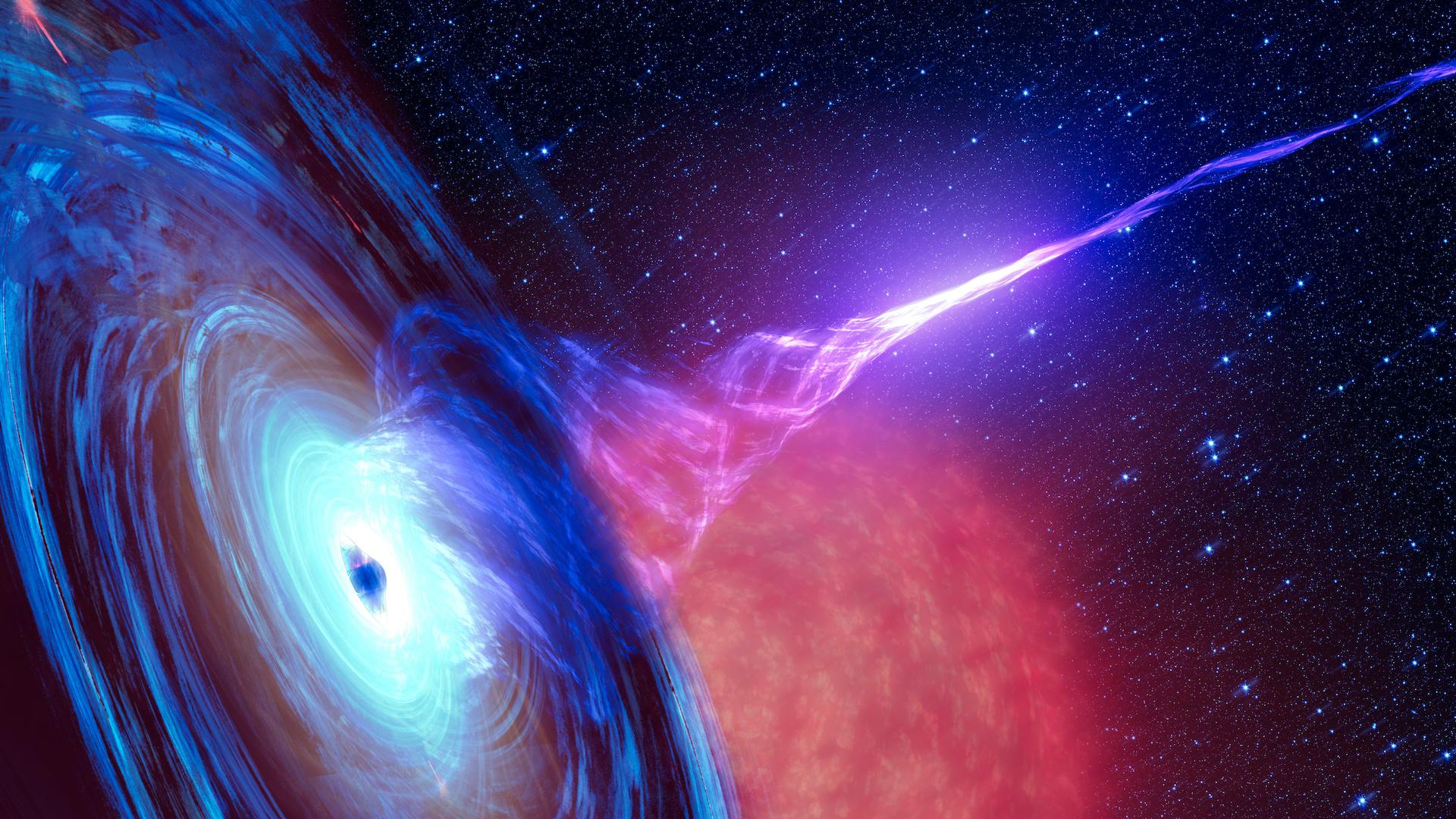

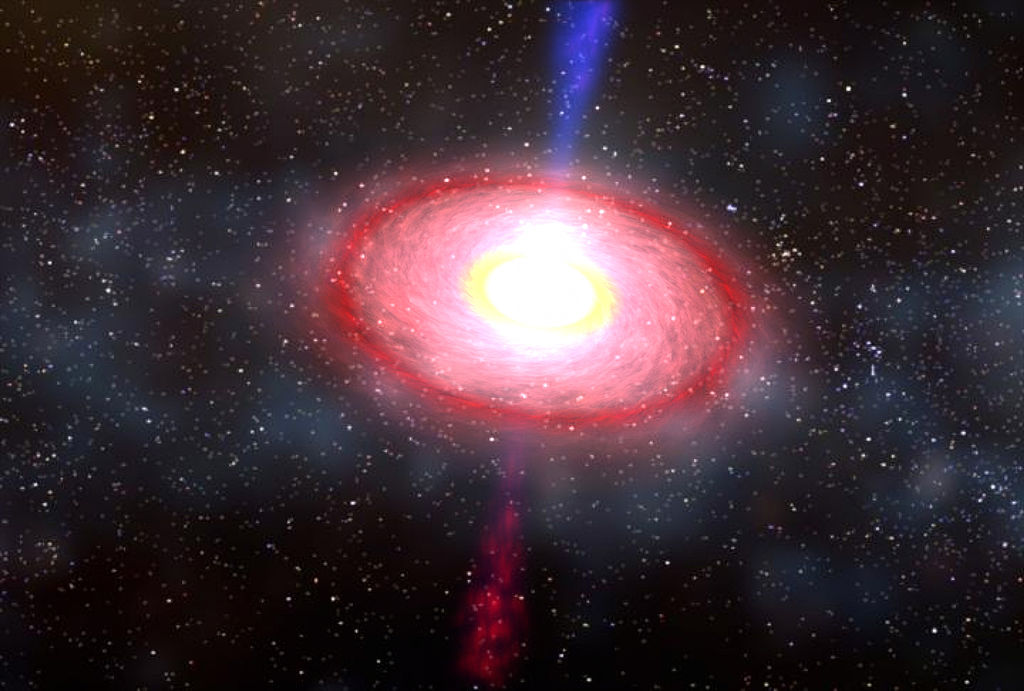

Researchers discover black holes that violate the uniqueness theorem and have “gravitational hair.”

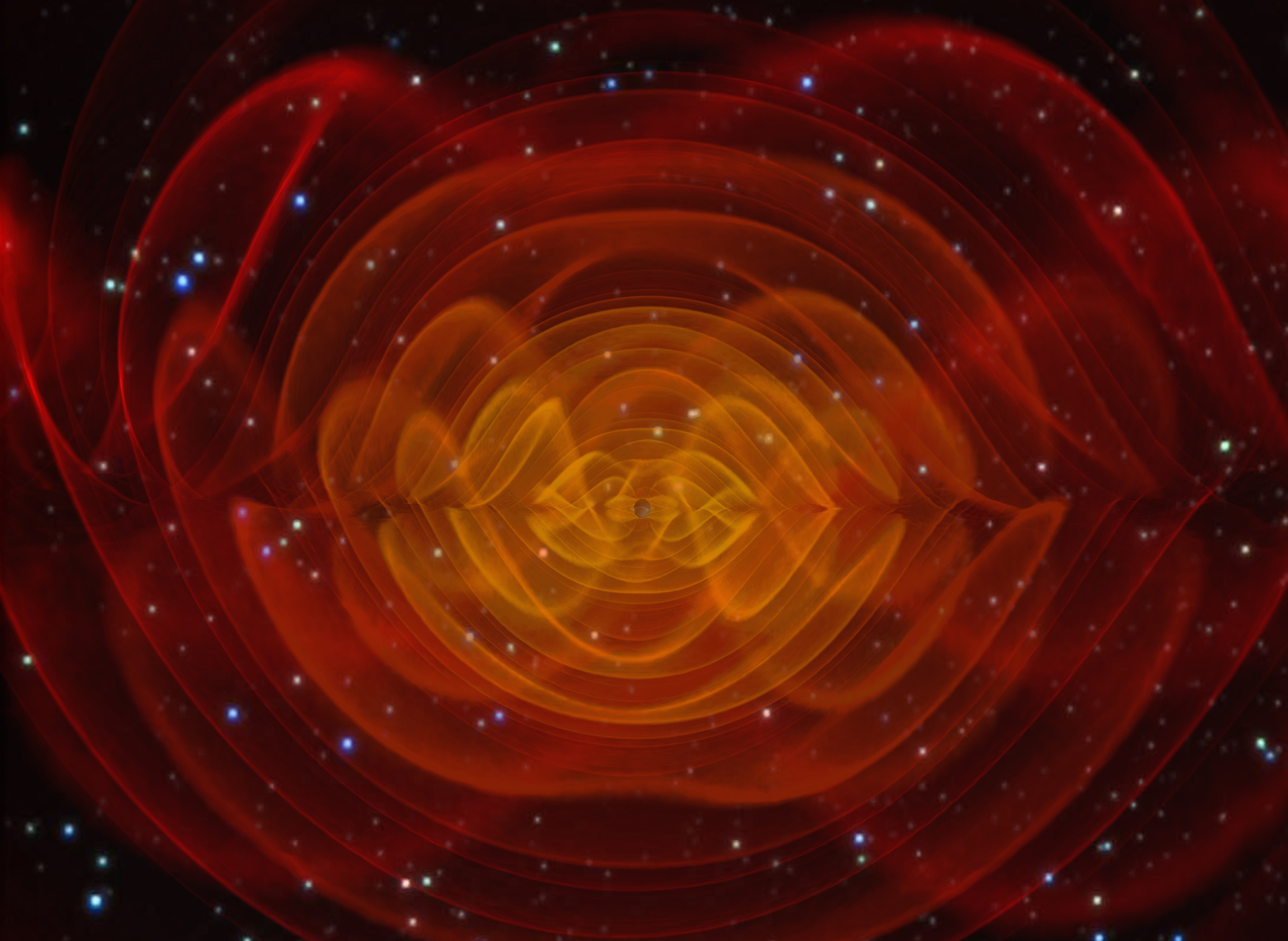

Gravitational wave researchers observe black holes of different sizes colliding for the first time.

▸

with

An Oxford scientist’s controversial theory rethinks dark matter and dark energy.

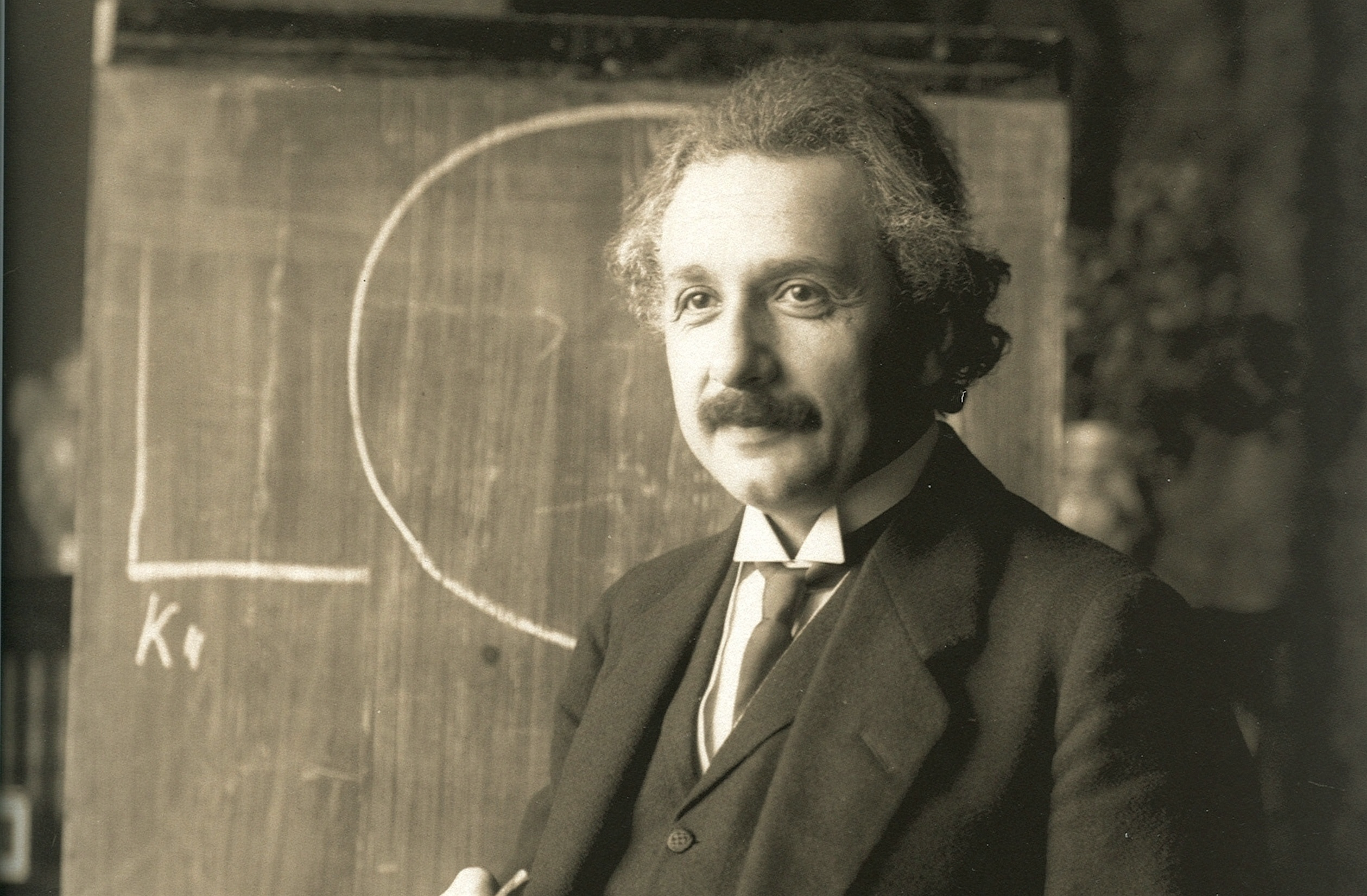

Erik Verlinde has been compared to Einstein for completely rethinking the nature of gravity.

Albert Einstein is synonymous with genius. While we’re all aware of his outstanding contributions to science, much of his brilliance is incomprehensible to us because it pertains to such an […]

Einstein’s God is infinitely superior but impersonal and intangible, subtle but not malicious. He is also firmly determinist.

Our experience of time may be blinding us to its true nature, say scientists.

What can cause a ripple in both space and time? Neutron stars colliding. And what can observe that phenomenon? A two-mile-long laser.

▸

5 min

—

with

Measuring quantum gravity has proven extremely challenging, stymying some of the greatest minds in physics for generations.

A groundbreaking experiment proves a key tenet of Einstein’s theory of gravity.

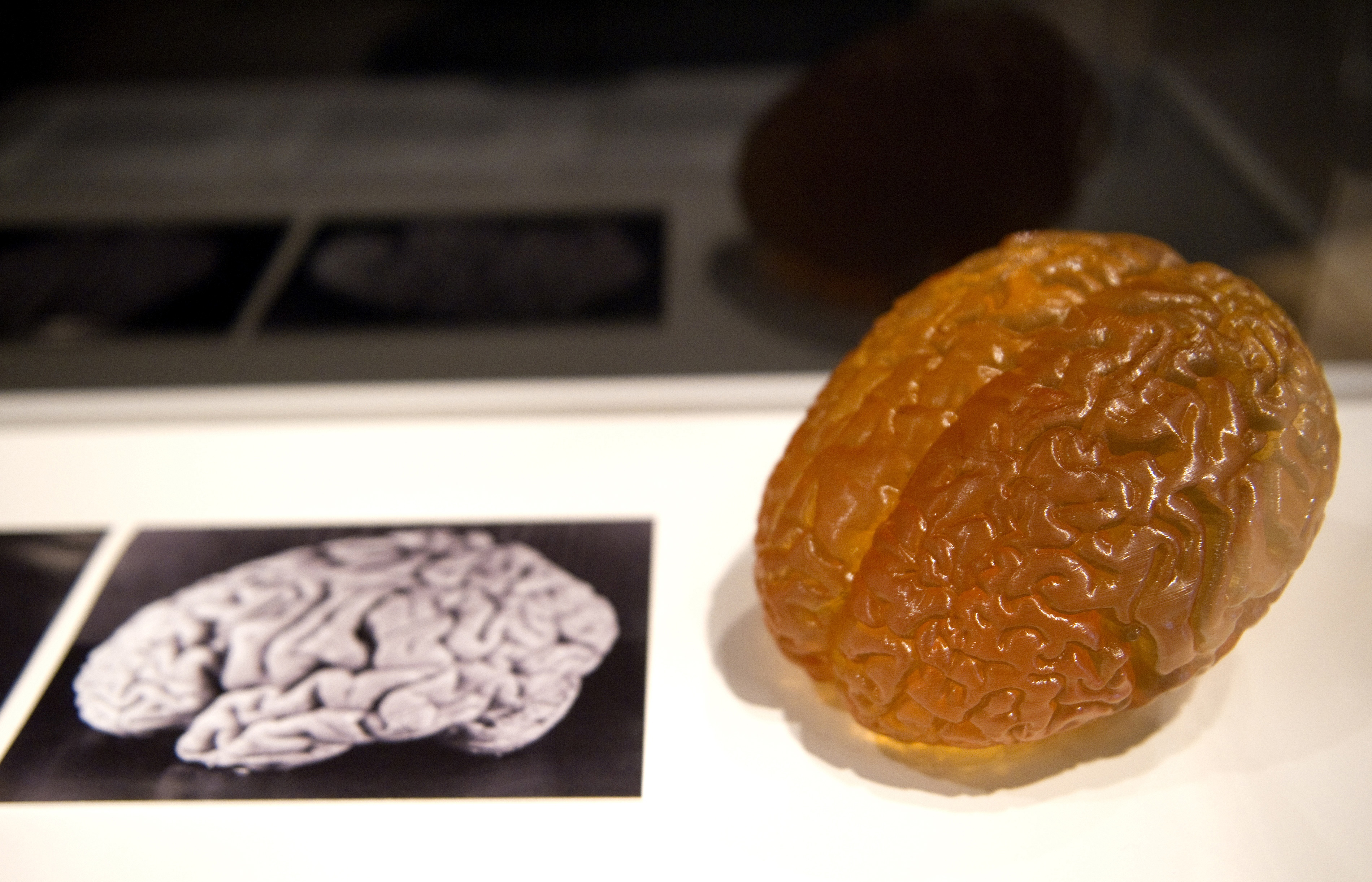

Here are four great brains from great minds, and how they differ from yours.

One prominent mathematician asks: was Einstein such a smartypants after all?

▸

10 min

—

with

This discovery finally points to the source of Earth’s precious heavy elements, also proves Einstein correct in more ways than one.

LIGO and Virgo reveal a gravitational wave was detected on two different continents. Here’s what that means and why it matters.

In 1936, a school girl named Phyllis wrote a letter to Albert Einstein to ask whether a person could believe in both science and religion. He was quick to reply.

Albert Einstein’s famous thought experiments led to groundbreaking ideas.

A new study challenges what we understand about the workings of time.

Here’s why you should try to fit less—not more—into each day.

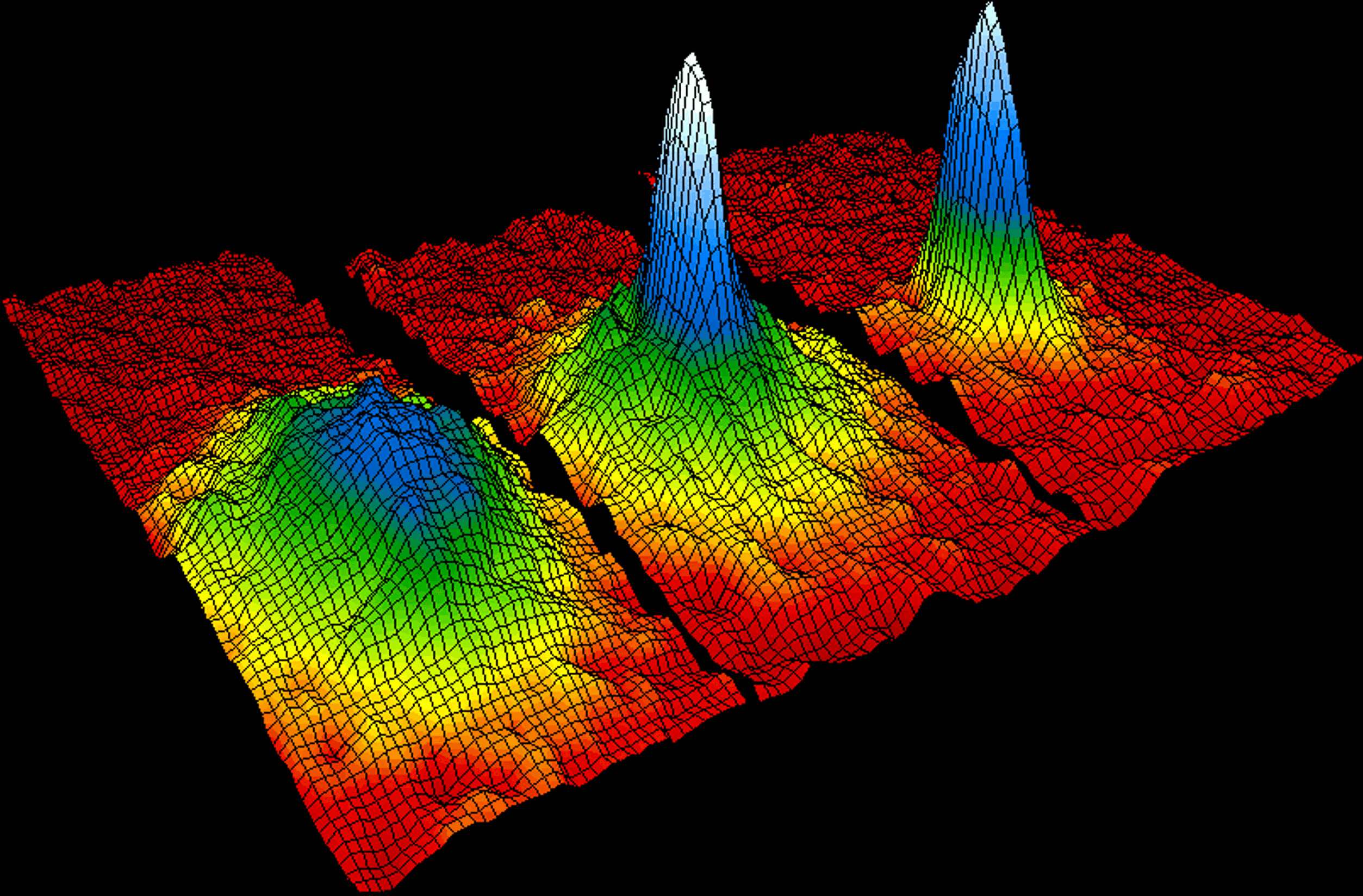

Scientists create a superfluid with negative mass that accelerates backwards.

Get ready for a decade of scientific revelations. Thanks to gravity waves, we have a completely new way to explore the universe.

▸

5 min

—

with

Scientists discover unusual galaxies that raise questions about Einstein’s theory of gravity and the existence of dark matter.

What happens up there directly affects life down here. From star-gazing to quantum mechanics, astronomy is one of humanity’s great thruster engines of innovation.

▸

5 min

—

with

Time is this wild fourth dimension in nature, says Bill Nye. We depend on its neat measurements for survival – but subjectively it continues to elude us.

▸

5 min

—

with

In 1905, Albert Einstein’s mother thought he was a genius, his sister thought he was a genius, his father thought he was a genius – but that was about it, says author David Bodanis.

▸

5 min

—

with

Are you the type of person who solves problems piecemeal, or with one great insight? A new study tells us the merits of each method.

Einstein believed his greatest blunder to have been the retraction of one of his equations but, as writer David Bodanis tells, the great scientist’s misstep actually happened immediately after.

▸

4 min

—

with

A theoretical physicist proposes a new way to think about gravity and dark matter.

Scientists produce a value for the cosmic microwave background that will definitely prove or disprove that the speed of light used to be higher.