egypt

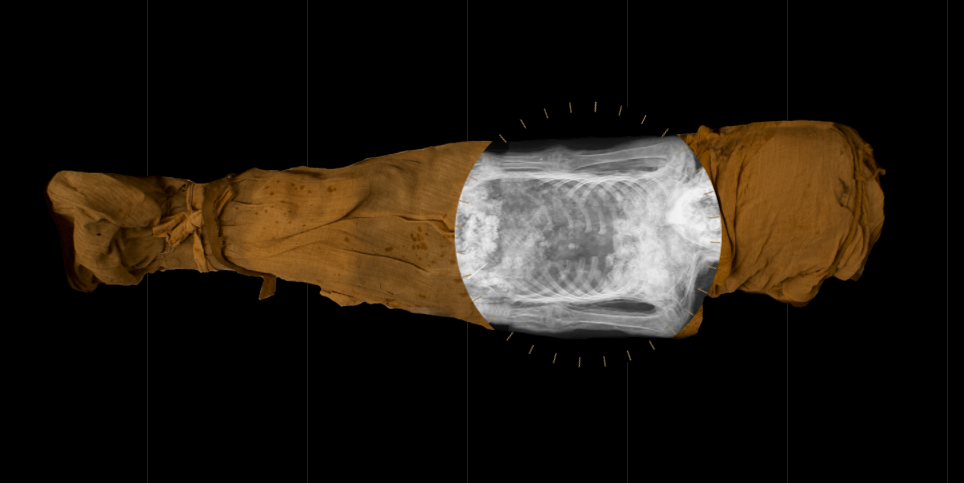

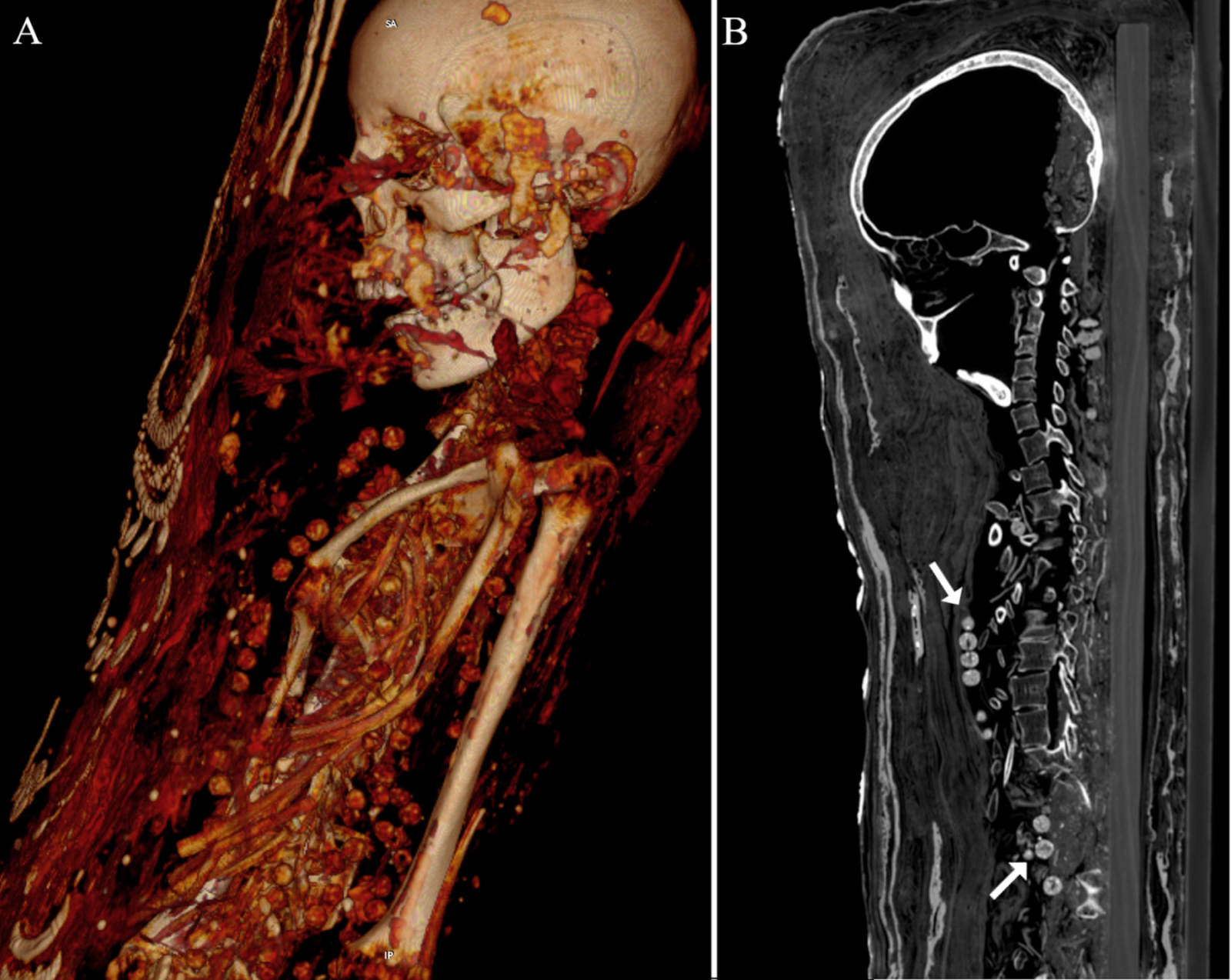

The mummy was first thought to be a male priest. But a recent radiological analysis revealed a surprising anomaly.

Meet a spectacular new blue—the first inorganic new blue in some time.

All the fun of opening up a mummy, without the fear of unleashing a plague.

Well preserved coffins hint towards more discoveries in a famed necropolis.

A few traditions in the Roman Catholic Church can be traced back to pagan cults, rites, and deities.

Researchers confirmed that the mummy known as Takabuti died from a stab wound to the back.

Scientists used CT scanning and 3D-printing technology to re-create the voice of Nesyamun, an ancient Egyptian priest.

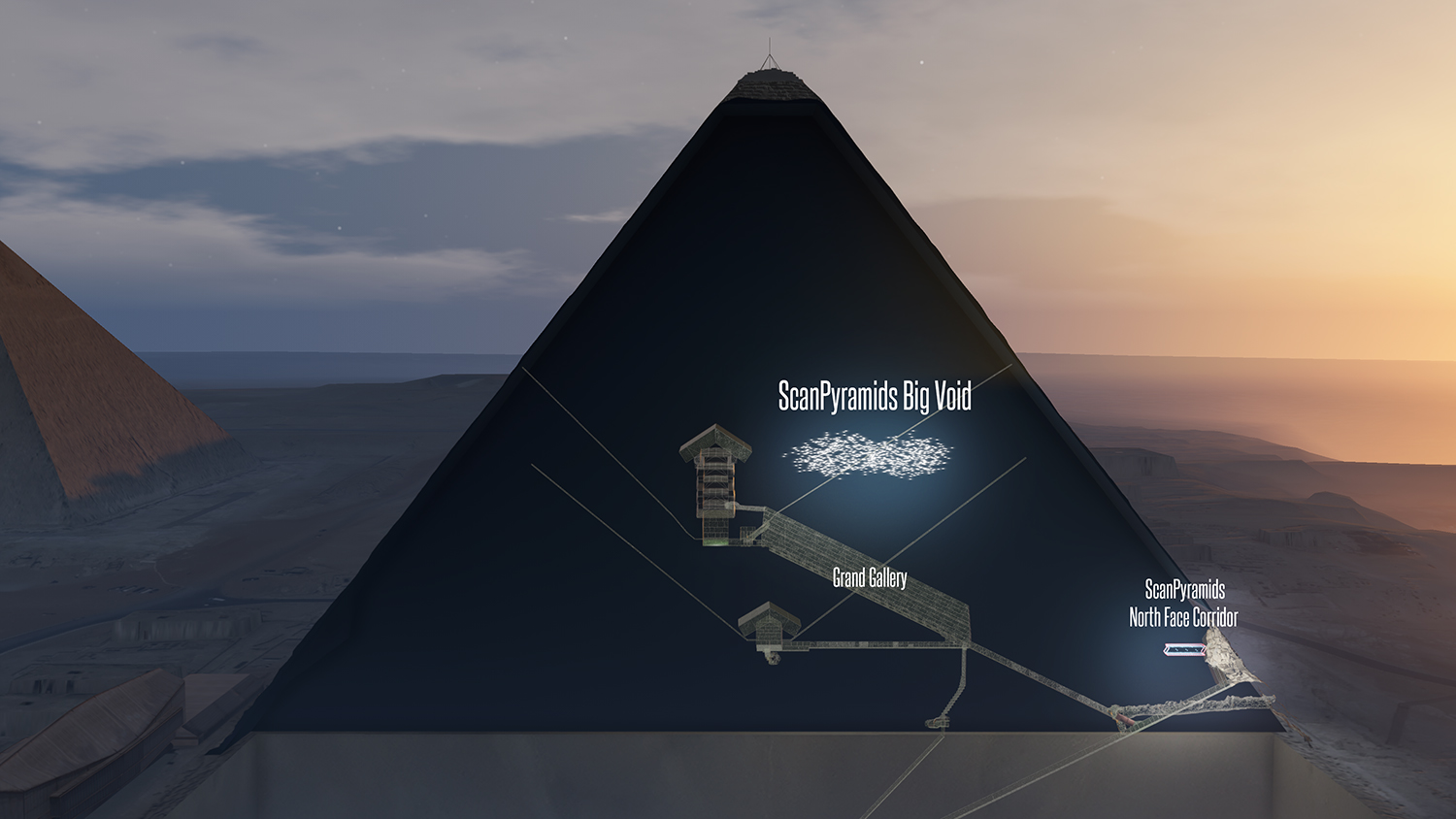

The inventor Nikola Tesla’s esoteric beliefs included unusual theories about the Egyptian pyramids.

The artifact will be opened on Sunday, for the first time in millennia, at an undisclosed location in Egypt.

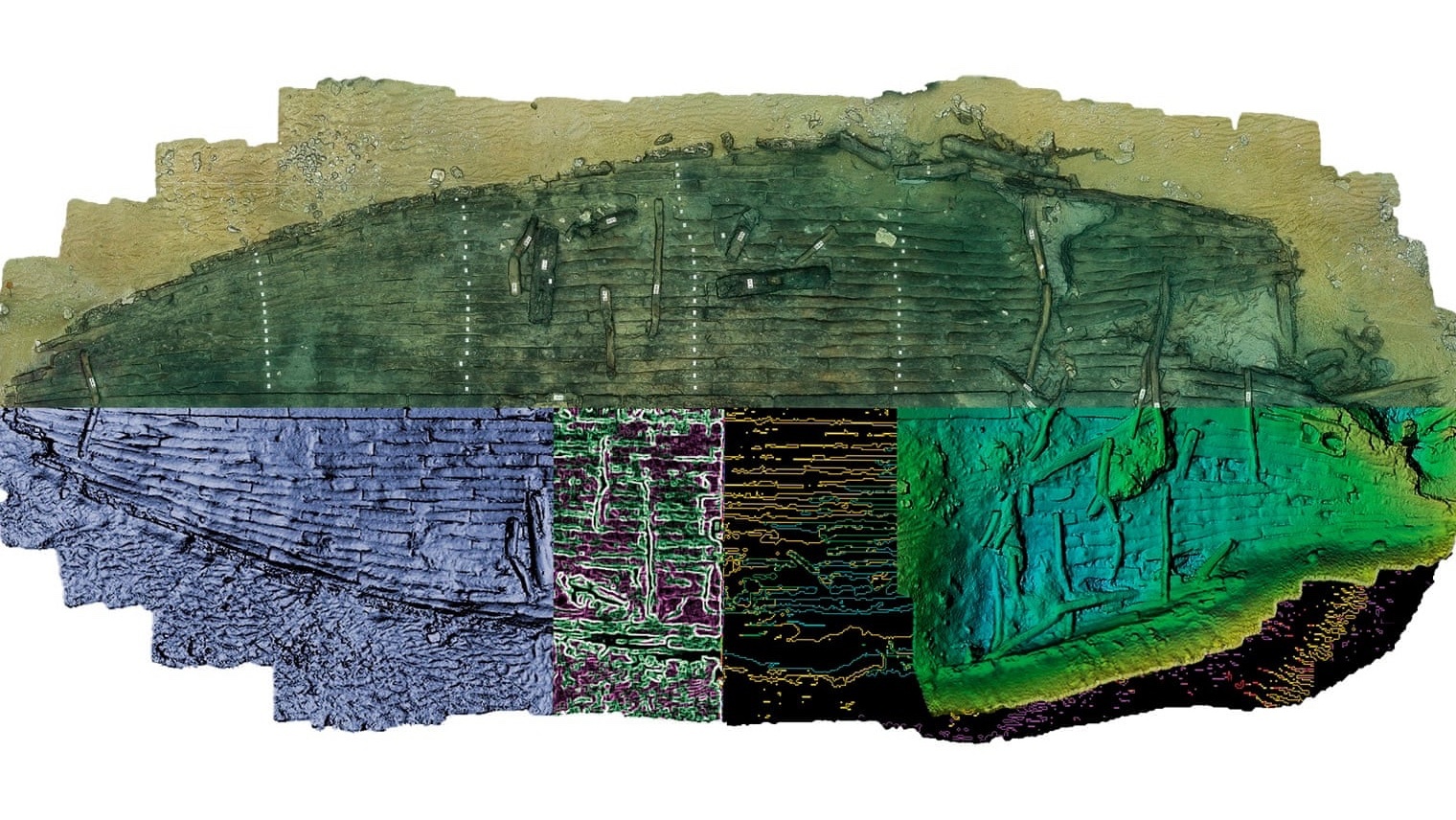

Archeologists had been doubtful since no such ship had ever been found.

Dozens of mummified cats were dug up this week. This isn’t as shocking as you might think.

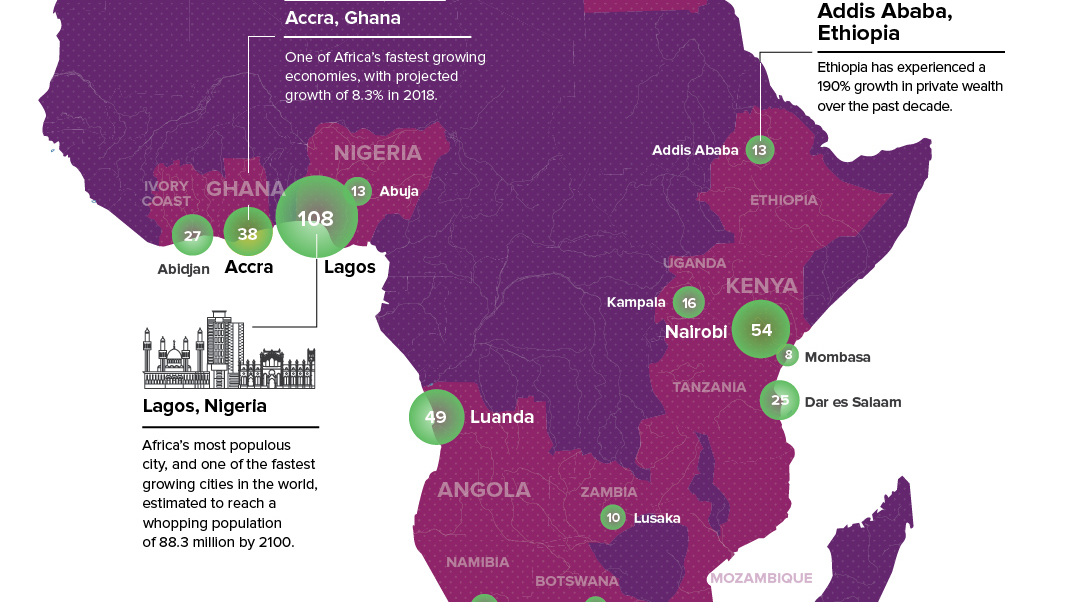

South Africa is no longer the only place on the continent that has urban wealth clusters

Researchers believe it may help uncover the secret to how the pyramid was built.