dogs

A new study tested to what extent dogs can sense human deception.

A new study finds that dogs fed fresh human-grade food don’t need to eat—or do their business—as much.

A study explores how your dog does when you’re not home.

A new study tracks the human-dog relationship through DNA.

New research sees dogs checking a North-South axis on their way home.

Admit it, caring for your pet can make you happy too. Science is working on why.

Learn where your ancestors are from, the breed of your rescue dog, and if your home is safe with these easy at-home kits.

The dogs’ ability to recognise and process human faces surpasses even that of monkeys. This newly-identified brain region may be the reason why.

Having a dog may be one way to curb lonelieness.

Could it simply be pleasure for its own sake?

The study also discovered a downside to having a big brain.

One type of dog in particular is linked with the lowest rates of cardiovascular disease in their human pals.

A new study shows that adult dogs can learn to distinguish generous and selfish people, but puppies can’t.

Funnily enough, some humans carry one of the very same genes.

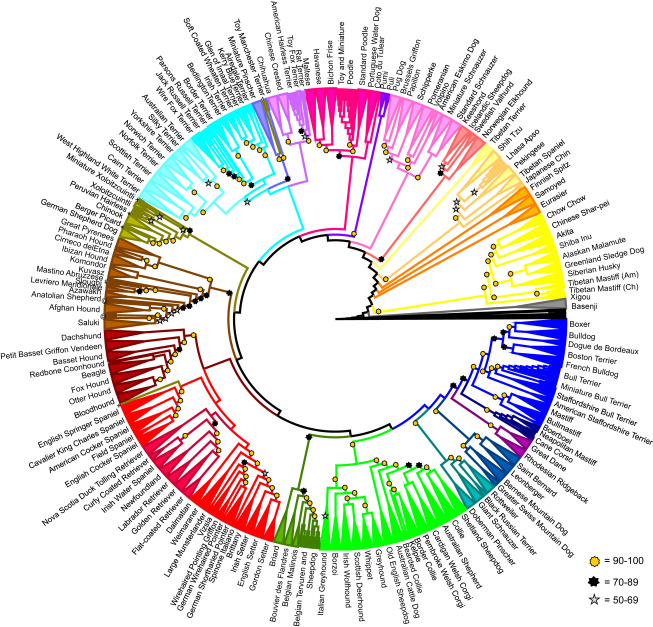

There are 400 breeds in total, including 23 distinct “clades” or types.

One day, we might be able to say that the dog saved the cheetah from extinction.

Animal-assisted therapy is increasingly being used nowadays. But does this practice make an impact?

A recent study from Yale University find that dogs are better at resisting peer-pressure and filtering useless information than human beings – but there’s value in that human flaw.