capitalism

As bad as this sounds, a new essay suggests that we live in a surprisingly egalitarian age.

The neoliberal call for more ‘choice’, seems hard to resist.

The British economic anthropologist Jason Hickel proposes “degrowth” in the face of recession.

Plan S is starting to take hold, but the cost is merely shifting even more to the researchers.

The next era in American history can look entirely different. It’s up to us to choose.

▸

5 min

—

with

Societies aren’t just engines of prosperity.

Finances can be a stressor, regardless of tax bracket. Here are tips for making better money decisions.

▸

15 min

—

with

In his new book, “American Rule,” Jared Yates Sexton hopes to overturn a centuries-long myth.

The American economy may be locked into an unhealthy cycle that only benefits a select few. Is it too late to fix it?

▸

19 min

—

with

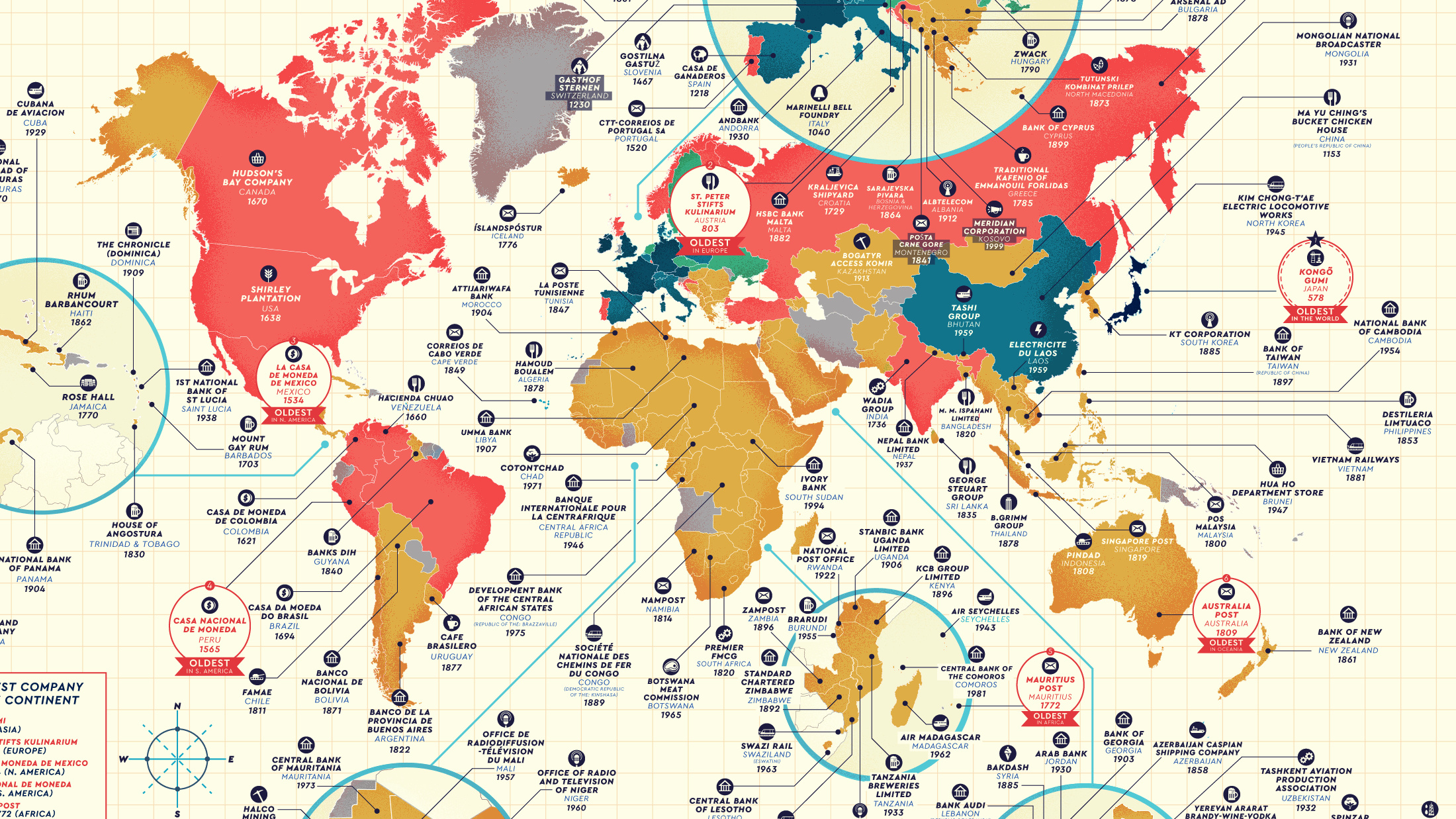

Maps show the oldest company in (nearly) every country – and a few interesting corporate trends.

Affluence could be our real downfall.

COVID-19 may strengthen the case for universal basic income, or an idea like it.

▸

24 min

—

with

Many of the most popular apps are about self-improvement.

An article in Journal of Bioethical Inquiry raises questions about the goal of these advocacy groups.

There are ways to engage with someone with whom you don’t agree.

▸

4 min

—

with

Transparency no doubt keeps organizations more accountable, but public companies need to reconnect with their true owners.

▸

4 min

—

with

Should pharmaceutical companies pay people for their plasma? Here’s why paid plasma is a hot ethical issue.

▸

17 min

—

with

The best and worst of yesterday has created the economy of today.

▸

7 min

—

with

How will the current challenges to the global economy pressure it to change?

▸

4 min

—

with

“Superstar” firms have been lowering labor’s share of GDP in recent decades, a new study finds.

Dissatisfaction is often linked to scandals and economic shocks.

In 2018, cancer drugs earned the pharmaceutical industry $123.8 billion. Soon, they’ll be worth billions more.

As little as an extra dollar could mean a significant decrease in suicide rates.

Next up on the countdown at #2, the world’s next superpower might just resurrect the Middle Ages.

▸

8 min

—

with

A photo showing two Alabama police officers bragging about a “homeless quilt” made from confiscated panhandling signs raises questions about the constitutionality of panhandling.

Continuing the countdown, Big Think’s seventh most popular video of 2019 explains why universal basic income will hurt the 99%, and make the 1% even richer.

▸

5 min

—

with

Clinical studies are underway. How we treat them moving forward matters.

Paying a fee for greenhouse gas emissions may spur a revolution, in terms of corporate behavior, amid the climate crisis.

▸

5 min

—

with

Can changing who delivers your electricity to you solve a slew of problems?