atheism

Seek pleasure and avoid pain. Why make it more complicated?

Spirituality can be an uncomfortable word for atheists. But does it deserve the antagonism that it gets?

Adam Frank, a card-carrying atheist and physics professor, wonders if there might be more to life than pure science.

Is death the final frontier? We ask scientists, philosophers, and spiritual leaders about life after death.

▸

14 min

—

with

In some countries, religiosity and pro-science attitudes are actually positively correlated, according to the results of a recent study.

The year 2020 will go down in history as one that shook our inner and outer worlds.

▸

with

Bastet was the daughter of the sun. The ancient Egyptian goddess was originally a fierce lioness warrior—a strong woman with the head of a big cat. Over time, her image […]

All that matters is the here and now.

▸

4 min

—

with

Do you get worried or angry? Ever forget to tithe? One minister has bad news for you.

A federal court ruled that the state of Kentucky was wrong to deny a man’s request for a personalized license plate reading “IM GOD.” Here’s why that’s a win against atheist discrimination.

Discrimination is up across the board.

From religious wars to French poison conspiracies to the counterculture, we look at the origins of Satanism.

Just because you don’t believe in God doesn’t mean you aren’t superstitious.

Is it saying too much to say something doesn’t exist when you have no evidence either way?

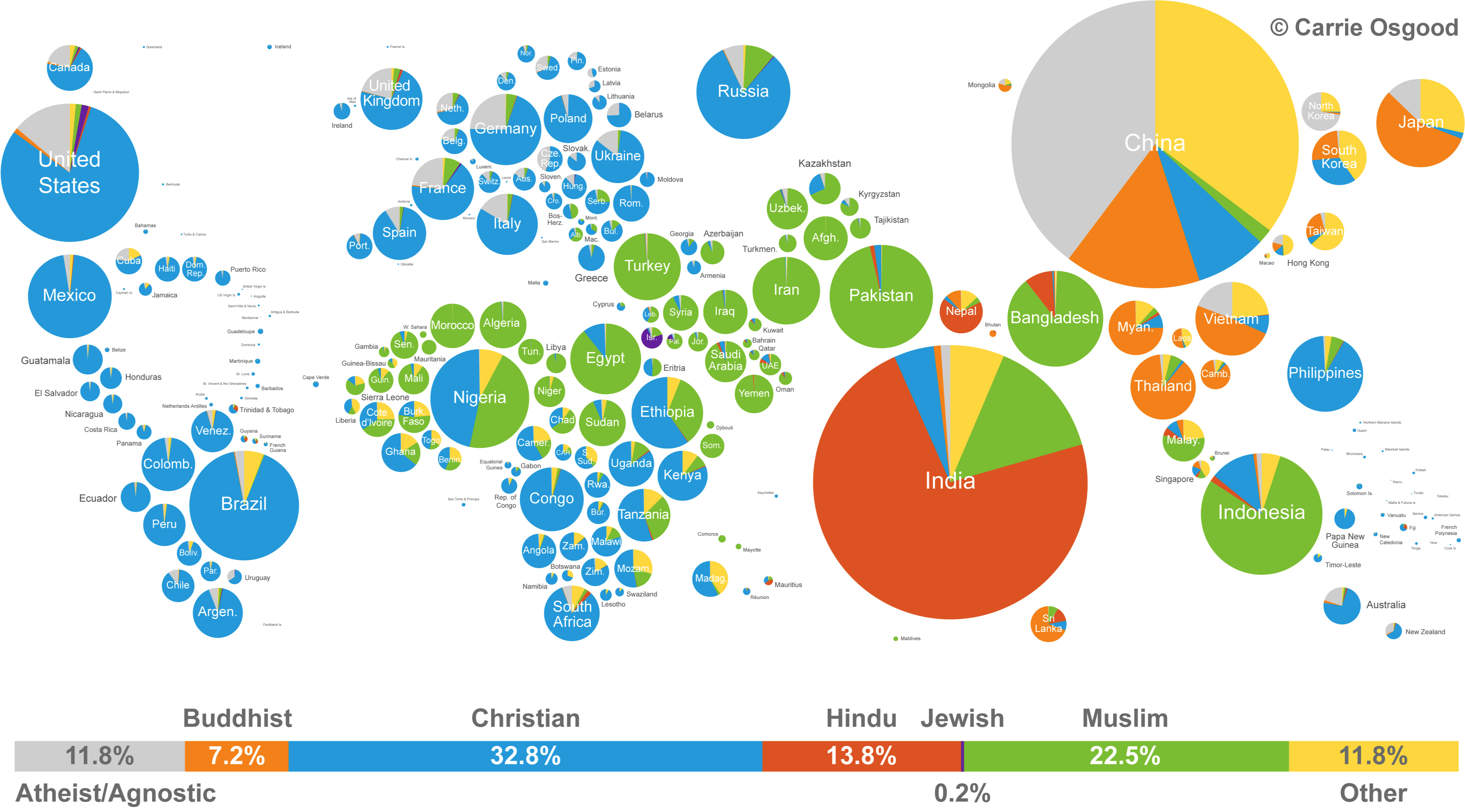

Both panoramic and detailed, this infographic manages to show both the size and distribution of world religions.

Going mad with Christmas cheer? Try one of these alternatives.

From psychology to neuroscience, what we believe is not nearly as relevant as why we do.

Eboo Patel explains how America’s political philosophy broke the democratic mold.

▸

4 min

—

with

Where is God? Michelle Thaller lays out a cosmic view of religion, science, and the human condition.

▸

5 min

—

with

All the prayers in the world to the Flying Spaghetti Monster probably won’t help.

This parody documentary skewers both the skeptic and the superstitious, and accurately shows what issues skeptics face.

▸

with

How to stay present and stop your mind from fixating.

▸

8 min

—

with

Do we really need an imaginary guy-in-the-sky to tell us what’s right and wrong? Not anymore, says Skeptic Magazine’s Michael Shermer.

▸

5 min

—

with

Existentialism is great and all, but how can you really relate to the ideas if you don’t think God is dead? Luckily, we’ve got just the thing.

Author, speaker, and public intellectual Richard Dawkins is a first-class debater on subjects as grand and reaching as the very existence (or lack thereof) of a master creator. But he’s got a simple yet highly effective technique to win people over to see his point of view. Find out what it is right here.

▸

3 min

—

with

You are going to die. So am I. These are facts.

Philosopher Tim Crane believes religion can be a rational, “intelligible human reaction to the mystery of the world.”

The U.S. has been steadily losing its religion for decades — but that trend might ramp up significantly in the years to come.

Hitler is commonly thought to have been an atheist, a claim that’s often used in debates about the perils of atheistic belief on a mass scale. But was he?