Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world for 265 years. Here’s why.

- Fearful of western influence, Japanese shoguns banned Christian missionaries before closing their borders altogether.

- Japan’s culture and industry thrived in global isolation, but this isolation also came at the cost of freedom and human lives.

- The complicated legacy of the so-called Sakoku period informs the international policies Japan pursues today.

On September 22, the Prime Minister of Japan, Fumio Kishida, announced the country would be reopening its border for tourists. Starting October 11, you will no longer need a visa to visit the Land of the Rising Sun, nor will you have to join a government-approved, guided tour. Best of all, Japan is abolishing its daily arrival cap, which at one point was set as low as 20,000 visitors.

These restrictions, some of the strictest in the entire world, were introduced at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, and remained in place long after other East Asian countries opened up their borders. Though effective in some ways – Japan’s COVID death toll is well below the global average – they have proven destructive in others, not in the least because Japan’s shrinking population and economy are becoming increasingly reliant on contact with the outside world.

Equally alarming were the double standards baked into Japan’s pandemic policies. Where other countries prohibited their own citizens from leaving just as they prevented foreigners from entering, Japanese citizens were allowed to visit any nation not in lockdown. And as one door opened, others remained firmly shut. The Asian news website Nikkei reported that about 370,000 guest workers and foreign students struggled to get back into Japan, even though they all had residence visas.

According to The Economist, Japan’s pandemic policies – which repeatedly discriminated where the coronavirus did not – betray its deeply rooted fear and distrust of foreigners. As former dean of Kyoto Seika University Oussouby Sacko explained, the country “conceptualised covid as something that comes from the outside,” and feared that tourists – in contrast to the notoriously clean and confirming Japanese – would not respect pandemic practices like mask wearing or silent eating.

The COVID pandemic may have reinvigorated anti-foreign sentiments in Japan, but the latter is much older than the former. Similar to the U.S. and other island nations, Japanese politics has been dominated by themes of isolationism and xenophobia for centuries. Once, under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, the country actually managed to completely sever all of its relations with the outside world. This period, now referred to as “Sakoku” or chained country, lasted 265 years.

The floating world

The seeds for Sakoku were sown in the late 16th century. During this time, Japan – a fiercely independent society that had successfully resisted incursions from other Asian powers – came into contact with European traders. Trade was accompanied by missionary work, which in relatively short time converted some 300,000 Japanese to Christianity. These conversions greatly worried Hideyoshi Toyotomi, a powerful feudal lord hailed as the “Great Unifier” of Japan. Hoping to curb Western influences, Toyotomi banned missionaries in 1587.

Toyotomi’s successors picked up where he had left off. They issued edicts that banned not just missionaries but non-Japanese people in general. Japanese, meanwhile, were prohibited from leaving the country. All trade relations with foreign nations were terminated with the exception of China, Korea, Japan’s indigenous inhabitants, and Dejima – a small island in the bay of Nagasaki, populated by employees of the Dutch East India Company.

Inside Japan, the Sakoku period is remembered as somewhat of a golden age. For 265 years, the Japanese lived in peace and considerable prosperity. United under the Tokugawa shogunate in a rigid but stable class system, the various clans that once kept the country divided now lived as one. Instead of waging destructive wars, they organized elaborate processions to demonstrate their wealth and military prowess. In one of his lectures, UNC professor Morgan Pitelka refers to Sakoku Japan as an instance where a country “recognized the possibility of colonialism and prevented it from happening.”

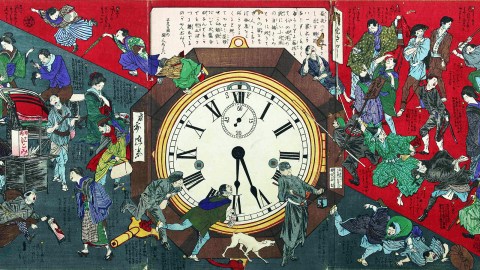

Established during this period was the concept of the “floating world,” which conceived of Japan as physically and spiritually separated from the default human experience, an experience characterized by conflict, corruption, plagues, poverty, and backbreaking work. Inside the floating world, time moved at a slower, more comfortable pace. More important than vying for power or making money – objectives that had different meanings in the aforementioned class system – was enjoying yourself.

Hence the infamy of Sakoku Japan’s pleasure districts: walled-off sections of major cities filled with various kinds of entertainment venues. Here you could visit kabuki theaters and tea houses. Inside the latter, customers enjoyed the company of geishas, who were as beautiful as they were skilled. Geishas could dance, sing, play music, and – on occasion – perform sexual favors. If sex was what all that you were after, though, you were better off visiting one of the countless brothels.

Unable to access foreign texts or commodities, Japanese culture developed inside a vacuum. This vacuum gave rise to unique artforms such as woodblock printmaking. While prints like Hokusai’s The Great Wave now decorate prestigious museums, they originally appealed to the masses as opposed to a cultural elite. Especially popular were posters advertising kabuki plays, which were mass produced and sold at cheap prices to villagers that did not have the money and resources necessary to travel to the cities and see the pleasure districts for themselves. In this sense, woodblock printmaking helped to connect Japan and endow its inhabitants with a shared visual language.

The bloody legacy of Sakoku Japan

The Sakoku edicts, though arguably beneficial for Japan’s economy and cultural production, were enforced through extreme violence. Entering or leaving Japan was punishable by death, a sentence all too eagerly enacted. In 1597, shogun Toyotomi ordered the execution of some 26 Christians, 20 of whom were Japanese, and one of whom was as young 12 years old. Their bodies were crucified. This practice, uncommon in Japan, was intended to send a message to missionaries as well as those considering conversion.

Pain and suffering could be found across Japan during the Sakoku period. In an article written for Narratively, the Tokyo-based writer Rob Goss described the island of Dejima as “not just a trading hub where the cultures of East and West met, clashed and occasionally even fell in love,” but also, as is to be expected of a society that arbitrarily separated people Romeo and Juliet-style, a place where “lives spectacularly fell apart.”

Dejima itself was more like a prison than an outpost. Traders who had been living in Japan were forced to relocate to this barely habitable island if they wanted to keep doing business with the country while the edicts were in place. Here they had to build their own buildings and facilities from scratch. Their only connection to the Japanese mainland, a bridge connecting the island to Nagasaki, was guarded day and night. It was also a one-way street.

Inhabitants had to concede not only their freedom of movement but also their faith, which – as Goss points out – they had no interest in spreading. Bibles and other religious scriptures were not allowed on Dejima. Sundays were reserved for work, not rest – and certainly not prayer. Even funeral services, as personal as they are spiritual, were strictly prohibited. “The dead,” Goss writes, “would have to be tossed into the sea.”

Reopening the borders

Japan’s isolationism was challenged on numerous occasions by foreign powers. The Portuguese attempted to gain access to the floating world in the 1640s. Envoys were sent to the capital city of Edo to plead with the shogunate. When they were summarily executed, Portugal returned with warships, accomplishing little except the bolstering of security forces in Nagasaki Bay.

Russia, France, and England tried their luck as well, but to no avail. Finally, in 1853, U.S. Navy commodore Matthew Perry broke into the bay of Edo with four warships armed with an unprecedented number of Phaixans guns: the first naval guns capable of firing explosive shells. The vessels, dubbed the kurofune or “black ships” by the Japanese, would have certainly been capable of breaking through a blockade. When Perry returned a year later with four more ships, the two countries signed a treaty confirming the establishment of diplomatic relations and opening of two Japanese trade ports.

The treaty marked the beginning of the end for Sakoku. In reality, however, the shogunate’s relationships with foreigners gradually relaxed over the course of their self-imposed exile. When the Dutch trader Hendrik Doeff set foot on Dejima in 1800, local authorities allowed the island’s inhabitants to cross the guarded bridge and visit the brothels in Nagasaki’s Maruyama district – a right that earlier generations would not have been granted. One of Doeff’s contemporaries, the Swedish botanist Carl Peter Thuberg, joined a procession to Edo. Inside the capital, the shogun questioned him about the outside world in exchange for samples of Japanese flora and fauna to study.

Dejima residents had visited Edo before, but under very different circumstances. “For Thunberg’s delegation,” writes Goss, “there was none of the court jester humiliation that had befallen early trips to Edo — no need to sing and dance for the shogun.”

Japan’s Sakoku period has a complicated legacy, one that is as bloody as it is beautiful. Historians continue to debate the extent to which the shogunate’s edicts helped or hurt the country. For a while, writes Robert Hellyr in a scholarship review, they were convinced that isolationism caused Japan to miss out on “vital stimuli from the West that might have allowed it to develop at a pace equal to that of Western nations.”

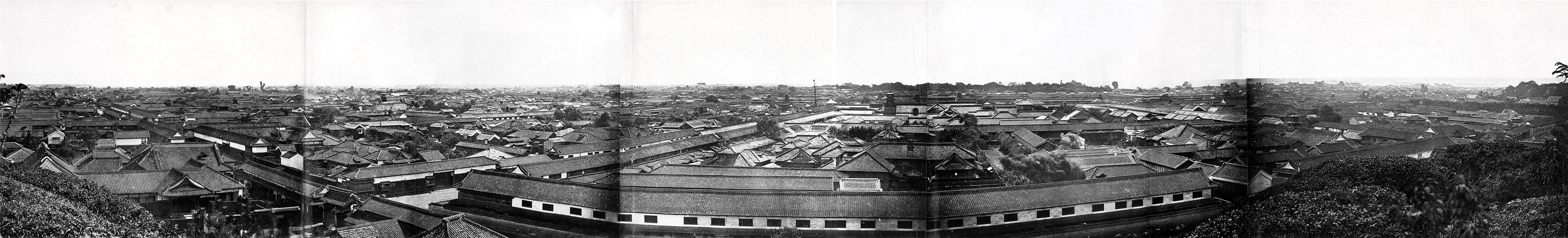

In recent years, that narrative has been called into question. True, Japan remained feudal while European countries industrialized, but that does not mean the floating world was completely resistant to change. As Pitelka mentions in his lecture, Sakoku Japan was surprisingly urban. With around a million inhabitants, Edo – or Tokyo, as it is known today – was the biggest city in the world, and twice as big as runner-up London. And the samurai, though still revered, were becoming increasingly indebted to Japan’s emerging merchant class: a sure sign that Japan was modernizing just the same.

At the same time, the downsides of isolationism cannot and should not be overlooked. When a civilization removes itself from the rest of the world, it automatically rejects all the good that could possibly result from cultural diffusion, from life-improving international relations to life-saving scientific innovations. The following passage from Gearoid Reidy, written for Bloomberg in response to Japan’s modern-day pandemic policies, could easily apply to Sakoku Japan as well:

“Japan’s out of sight, and threatens to become out of mind with one its main lines of communication to the world still cut — the tens of millions of tourists who returned home each year with gushing tales of encounters with the country’s people, culture and food.”