virtual reality

The time to begin exploring VR training is now. Here are the pros, cons, and different ways this technology can be utilized.

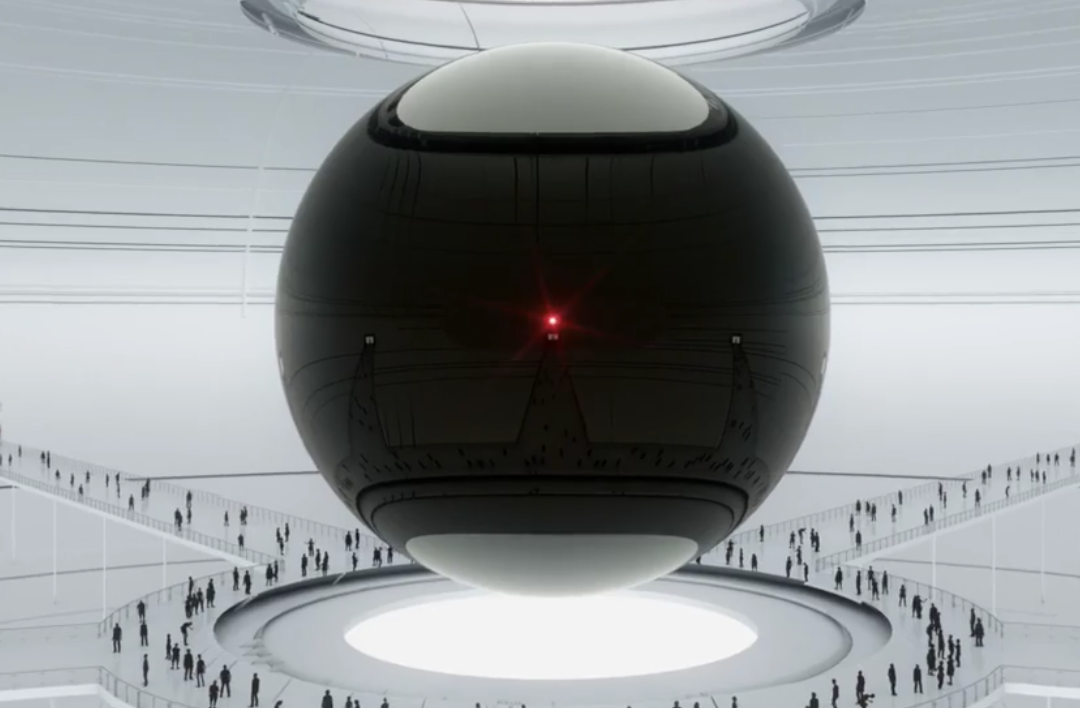

Think of a combination of immersive virtual reality, an online role-playing game, and the internet.

Virtual reality continues to blur the line between the physical and the digital, and it will change our lives forever.

Virtual tourism has thus far been a futuristic dream, but a world shaped by Covid-19 may be ready to accept it.

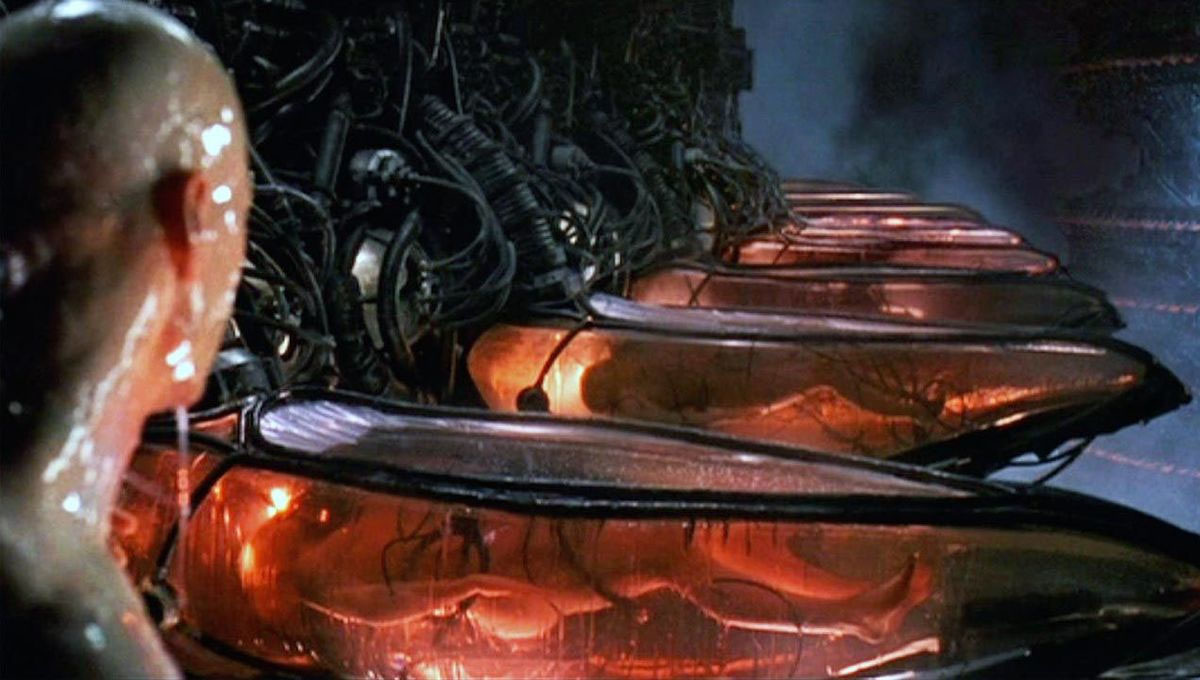

A famous thought experiment from the 1970s is more relevant today than ever before.

A new study calls the technique “location spoofing.”

Ever lose track of time while doing something? It gets worse with a VR headset on.

A new study looks at how images of coffee’s origins affect the perception of its premiumness and quality.

What happens when simulation theory becomes more than a fascinating thought experiment?

New research shows that experiencing an opposite-sex body in virtual reality impacted the subject’s gender identity.

“Interacting” with nature through virtual reality applications had especially strong benefits, according to the study.

Virtual reality is more than a trick. It’s a solution to big problems.

▸

11 min

—

with

Researchers are using technology to make visual the complex concepts of racism, as well as its political and social consequences.

▸

5 min

—

with

The line between work and play has became blurred during the pandemic.

Take the circumstances in your life seriously, but not literally. Here’s why.

▸

27 min

—

with

Exploring the idea that objects we perceive in everyday life do not reflect objective reality.

▸

3 min

—

with

Study looks at who/what they prefer learning from

How could we create a technology capable of replacing our own reality?

VR’s coolest feature? Boosting compassion and empathy.

▸

3 min

—

with

What would it be like to live in the body of someone else? With VR, now you can actually find out.

▸

4 min

—

with

By being someone else, and seeing and discovering the world through the eyes of other people, that can only increase our empathy… and decrease our own egocentric view of the world.

▸

4 min

—

with

Events, entertainment, and transportation are literally being transformed during this year’s Olympics.

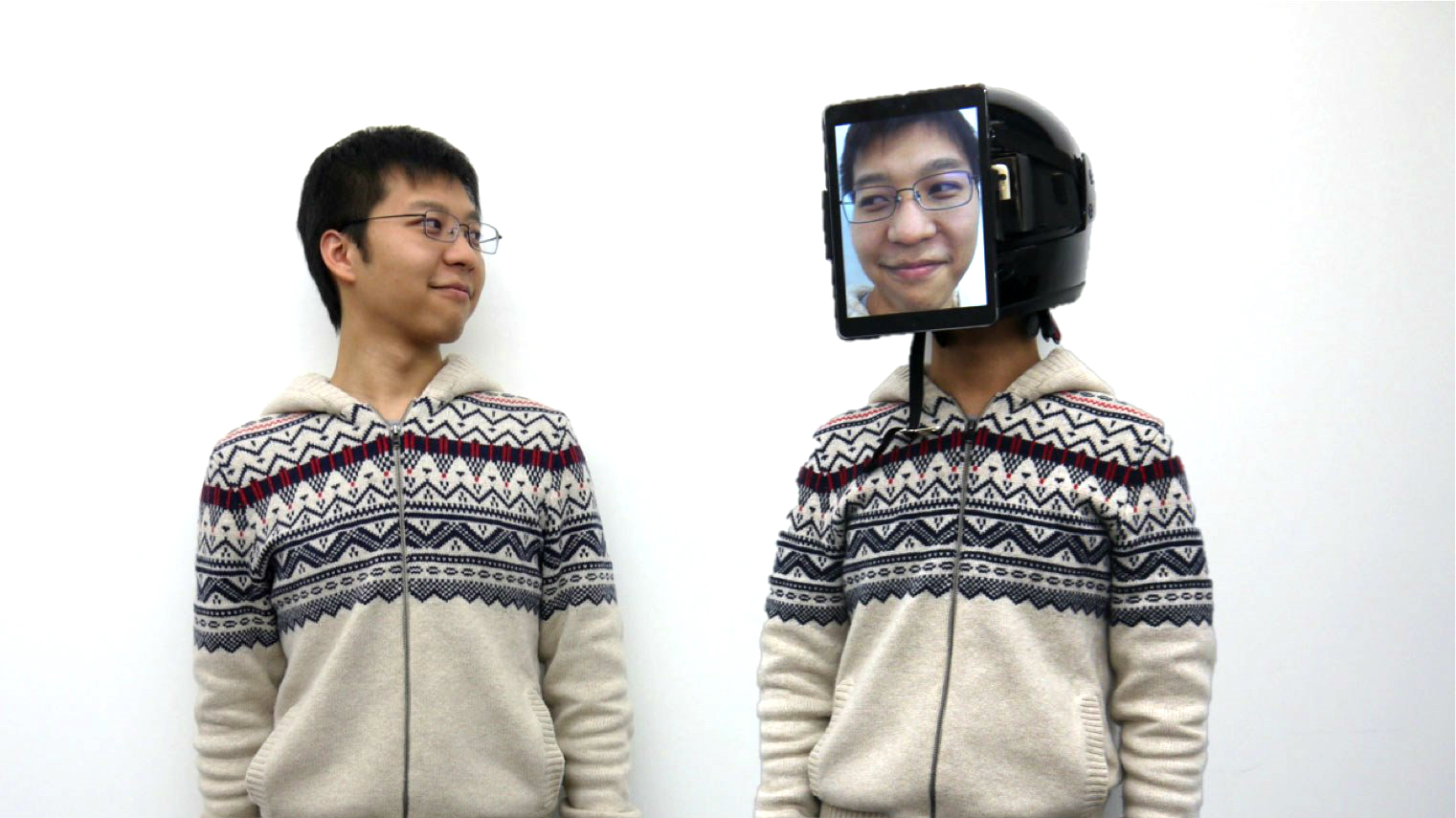

A new technology hopes to provide customers with “human surrogates” who strap screens to their faces so they can interact with the world on customers’ behalf.

Soon, the line that divides the living from the dead might not be so clear.

Your future happiness and success will depend on the double-edged sword of embracing new technology to stay connected, and being smart enough to unplug at the right time.

▸

9 min

—

with

Reality is whatever your body believes. Virtual reality knows how to hack that.

▸

5 min

—

with

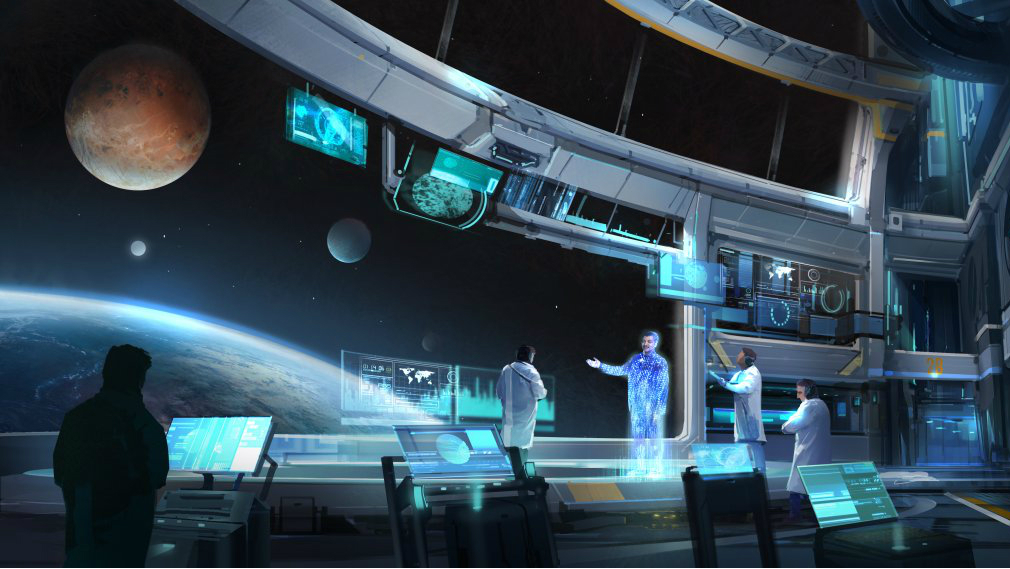

Neil deGrasse Tyson is working in with video game developers to create a space exploration game called Space Odyssey.

A new study suggests always-improving video games are keeping young men without college educations unemployed or out of the workforce entirely.

When you take off a virtual reality headset, you don’t remember seeing things, you recall experiencing them, says Kevin Kelly. VR will create a world of amazing opportunity – for us and for advertisers.

Two billionaires are apparently funding research into how we can escape the simulation they believe we’re trapped in.