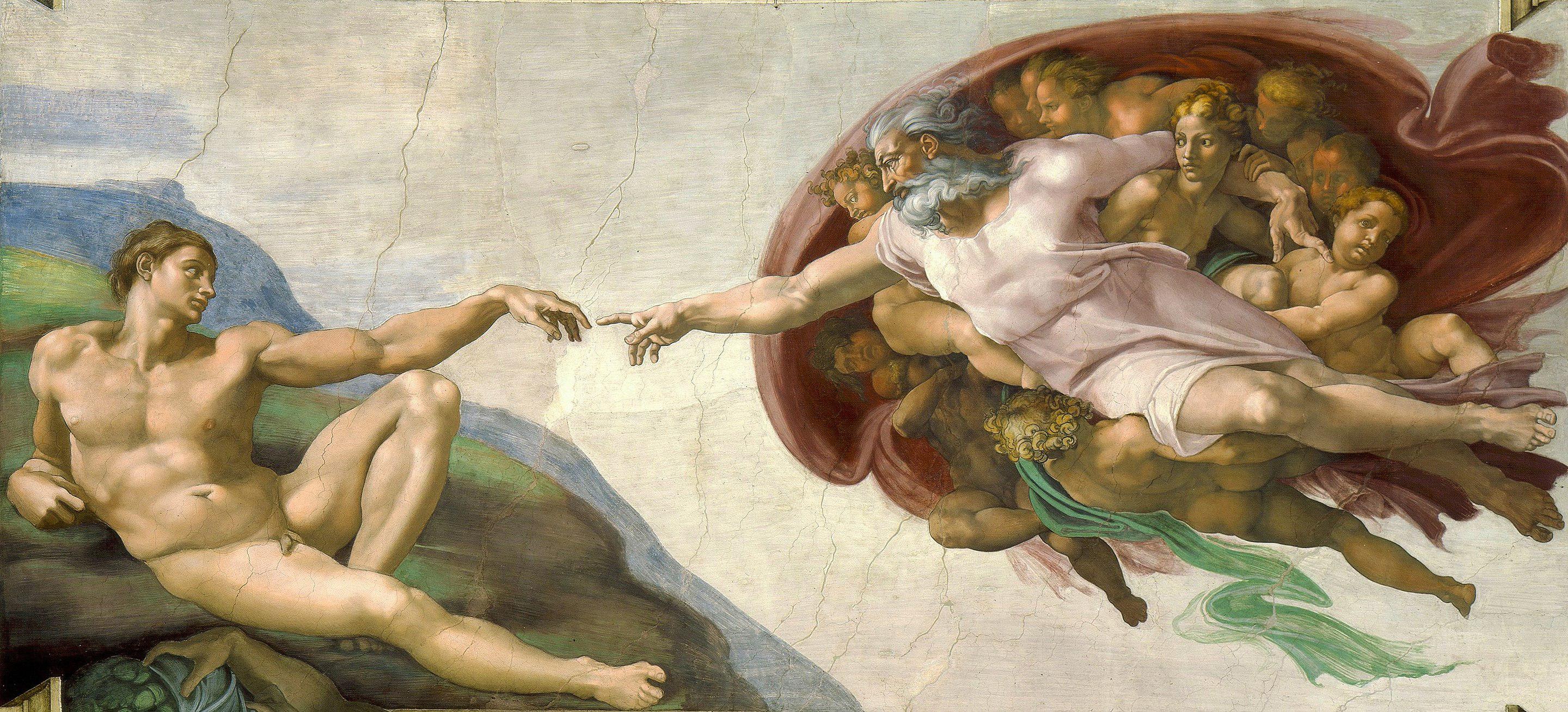

God

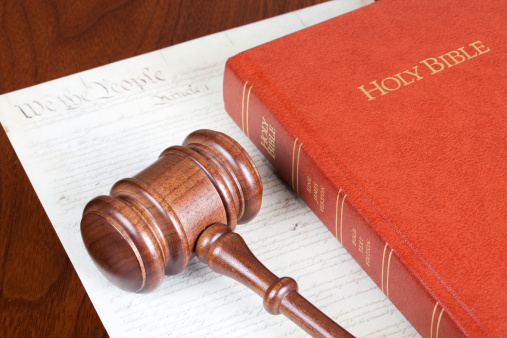

Apart from divine authority, is there an ethical basis for right and wrong?

Regularities, which we associate with laws of nature, require an explanation.

Here’s what Einstein meant when he spoke of cosmic dice and the “secrets of the Ancient One”.

Research shows that bone fragments of Jesus’s (possible) brother belong to someone else.

Is death the final frontier? We ask scientists, philosophers, and spiritual leaders about life after death.

▸

14 min

—

with

Christians and Muslims that pick out unconscious patterns are more likely to believe in a god.

Placing science and religion at opposite ends of the belief spectrum is to ignore their unique purposes.

▸

14 min

—

with

All that matters is the here and now.

▸

4 min

—

with

Philosophy professor James Sterba revives a very old argument.

A federal court ruled that the state of Kentucky was wrong to deny a man’s request for a personalized license plate reading “IM GOD.” Here’s why that’s a win against atheist discrimination.

A new book by constitutional attorney Andrew Seidel takes on Christian nationalism.

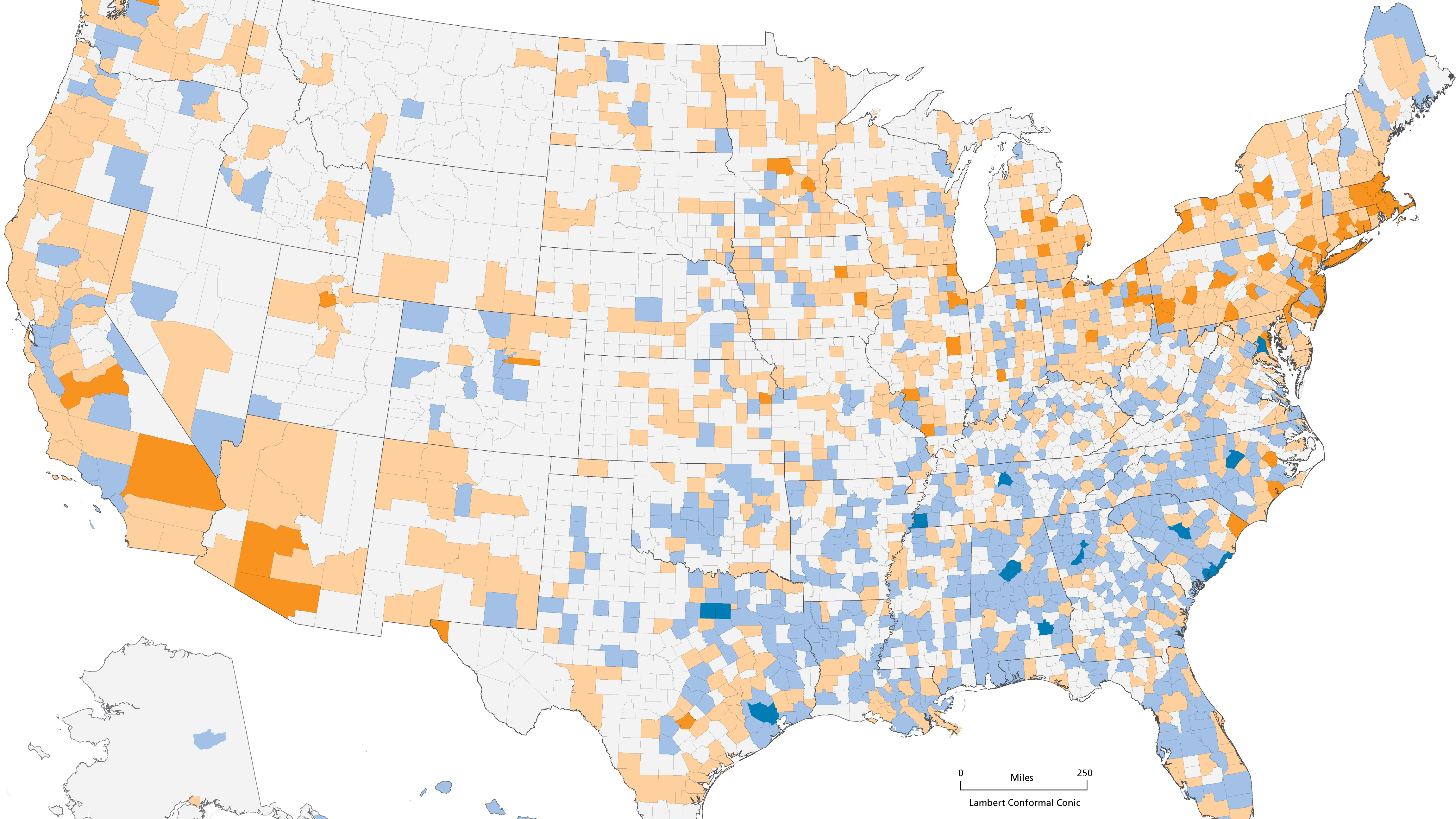

How deep are America’s cultural fault lines? Depends on which data you crunch.

Atheism doesn’t offer much beyond non-belief, can secular humanism fill the gaps?

Does God exist? The answer rests outside the “normal” boundaries of science.

▸

3 min

—

with

Symbols are often used to help people get an idea of higher, often ineffable, truths.

▸

8 min

—

with

Comedian Pete Holmes details his struggle with faith, sex, and God.

▸

10 min

—

with

Is it saying too much to say something doesn’t exist when you have no evidence either way?

Surprisingly, many of the world’s most popular religions have a lot to do with anarchy.

Einstein’s God is infinitely superior but impersonal and intangible, subtle but not malicious. He is also firmly determinist.

Was Jesus a real historical figure? Here’s what we know.

From psychology to neuroscience, what we believe is not nearly as relevant as why we do.

Thousands of churches are left behind every year in America.

Where is God? Michelle Thaller lays out a cosmic view of religion, science, and the human condition.

▸

5 min

—

with

Maybe we should stop worrying about what happens after we die, and make the best of what we have on earth right now.

▸

6 min

—

with

Jordan Peterson is one of the most controversial public figures in recent years. Here’s a recap of some of his ideas.

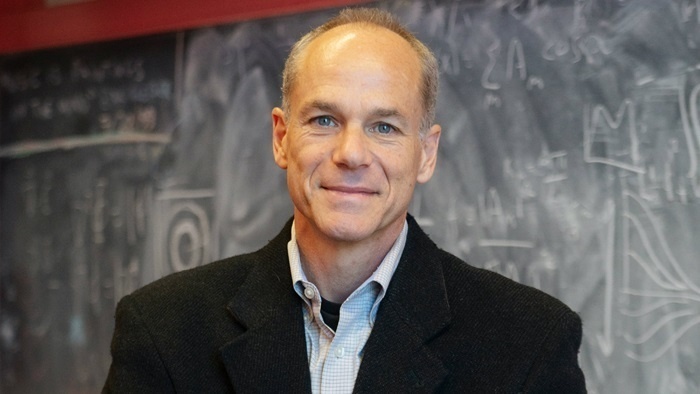

Michael Shermer responds to the discussion over his article, “Will Science Ever Solve the Mysteries of Consciousness, Free Will and God?”

▸

with

Do we really need an imaginary guy-in-the-sky to tell us what’s right and wrong? Not anymore, says Skeptic Magazine’s Michael Shermer.

▸

5 min

—

with