disease

This network scientist is creating a map of the human genome, and it could revolutionize the future of healthcare.

▸

6 min

—

with

A new device cured the hiccups 92 percent of the time in a recent study involving more than 200 participants.

“The question is which are okay, which are not okay.”

▸

14 min

—

with

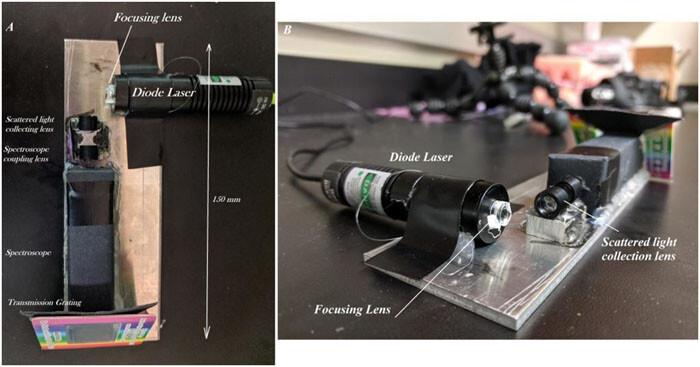

A team of scientists managed to install onto a smartphone a spectrometer that’s capable of identifying specific molecules — with cheap parts you can buy online.

For every good idea in evolution, there is an unintended consequence. Disease is often one of them.

A newly discovered coronavirus — but not the one that causes COVID-19 — has made some dogs very sick.

Are “humanized” pigs the future of medical research?

The new treatment targets the underlying genetic cause of the disease.

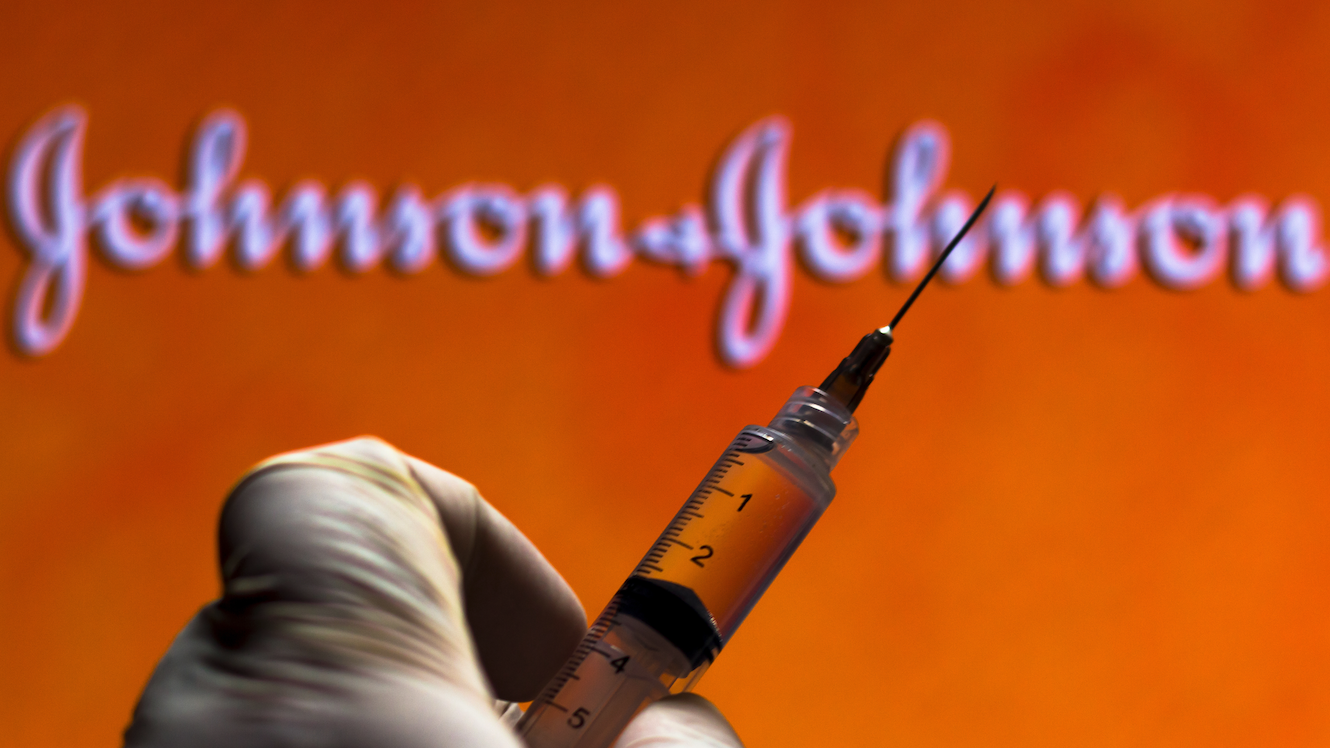

Millions of doses of Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine could be distributed as early as this week.

Trained dogs can detect cancer and other diseases by smell. Could a device do the same?

The study suggests scientists are underestimating the number of animal species that could generate the next novel coronavirus.

The main bioactive compound in catnip seems to protect cats from mosquitoes. It might protect humans, too.

We look back at a year ravaged by a global pandemic, economic downturn, political turmoil and the ever-worsening climate crisis.

A new study on mice showed that ginger may counter certain autoimmune disorders such as lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome.

A new study suggests that maintaining gut health to avoid diabetes may be little simpler than previously believed.

A new antibiotic hits germs with a two pronged attack.

What lies in store for humanity? Theoretical physicist Michio Kaku explains how different life will be for your descendants—and maybe your future self, if the timing works out.

▸

15 min

—

with

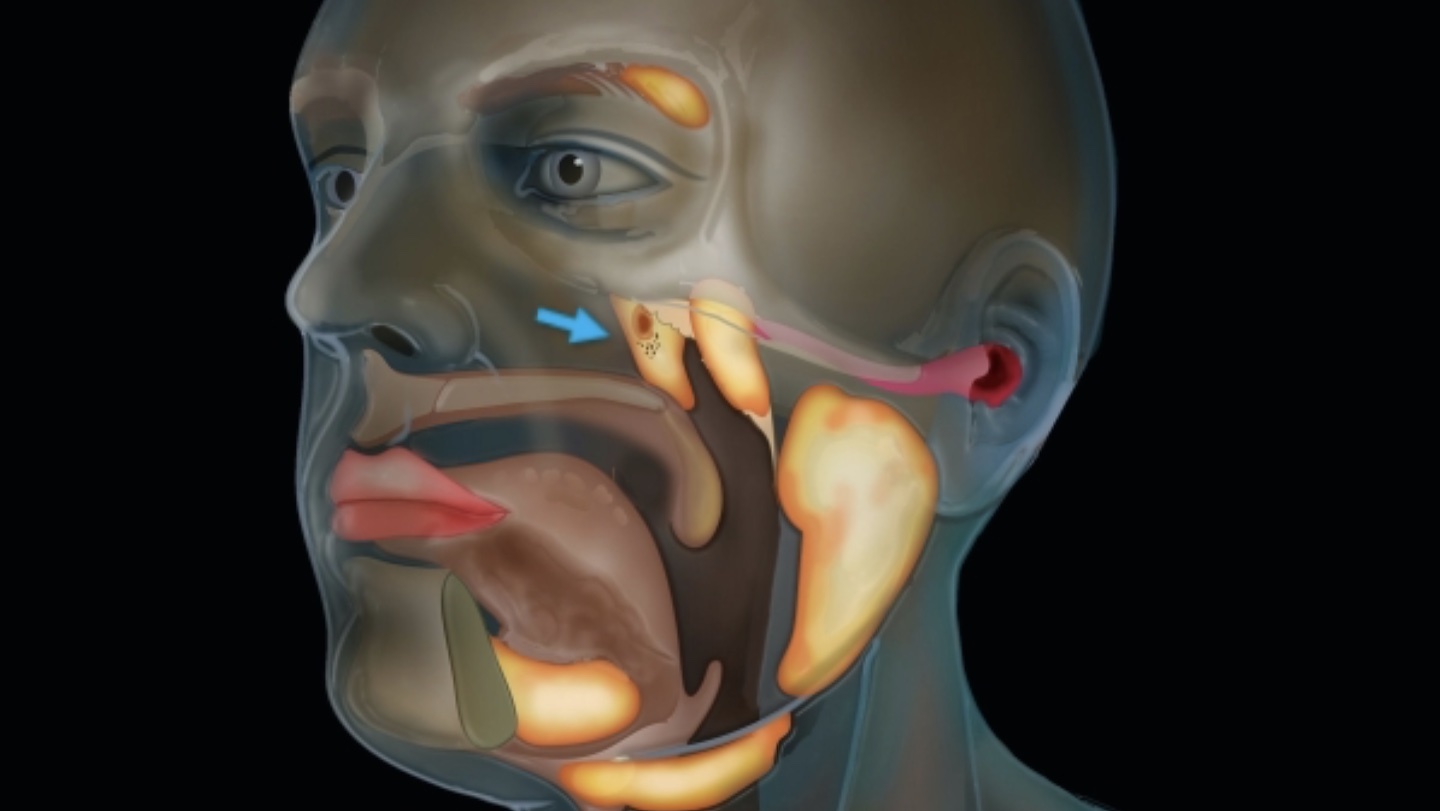

New cancer-scanning technology reveals a previously unknown detail of human anatomy.

Mosquitoes can taste your blood using unique sensory abilities. Can we use that to keep them off us?

Researchers from the University of Toronto published a new map of cancer cells’ genetic defenses against treatment.

Archaeology clues us in on the dangers of letting viruses hang around.

A large-scale study from King’s College London explores the link between genetics and sun-seeking behaviors.

Stewart is supporting a new bill that aims to extend health care and disability benefits to veterans who served alongside burn pits.

Why a survey claims Boomers demonstrate more knowledge and safer behavior.

The images were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and show how prolific coronavirus can become in a mere four days.

Some people choose alternatives to masks for comfort. A study shows the difference in effectiveness.

Despite Boseman’s young age, this cancer is increasingly common in people under 50.

On the list of animals at risk are several endangered species.

One reason to suspect you have COVID-19 may be the order in which the symptoms appear.

A study published Friday tested how well 14 commonly available face masks blocked the emission of respiratory droplets as people were speaking.