Lessons of Cancer = Evolutionary Civil War

This is the third diablog between David Sloan Wilson (DSW, head of The Evolution Institute, and author of Does Altruism Exist?) and me (JB).

JB: Having covered how evolution keeps score (relative fitness), and its built-in team aspects, let’s now consider a kind of naturally counterproductive competition.

Your mention of “intragenomic conflict” surprised me. Wouldn’t consuming resources in internal conflict be an evolutionary handicap? Wouldn’t evolution select against organisms whose parts worked against each other?

How common is intra-organism conflict? What are its lessons?

DSW: Cancer provides a fine example of intragenomic conflict. All of our cells descend from a single cell, but they are not genetically identical — despite counterclaims— because mutations can occur in any cell division.

Human adults have ~60 trillion cells, of which ~500 billion turn over daily. This results in many, many mutations. Some mutations cause cells to proliferate at the expense of neighboring cells, forming neoplasms, which can become deadly tumors.

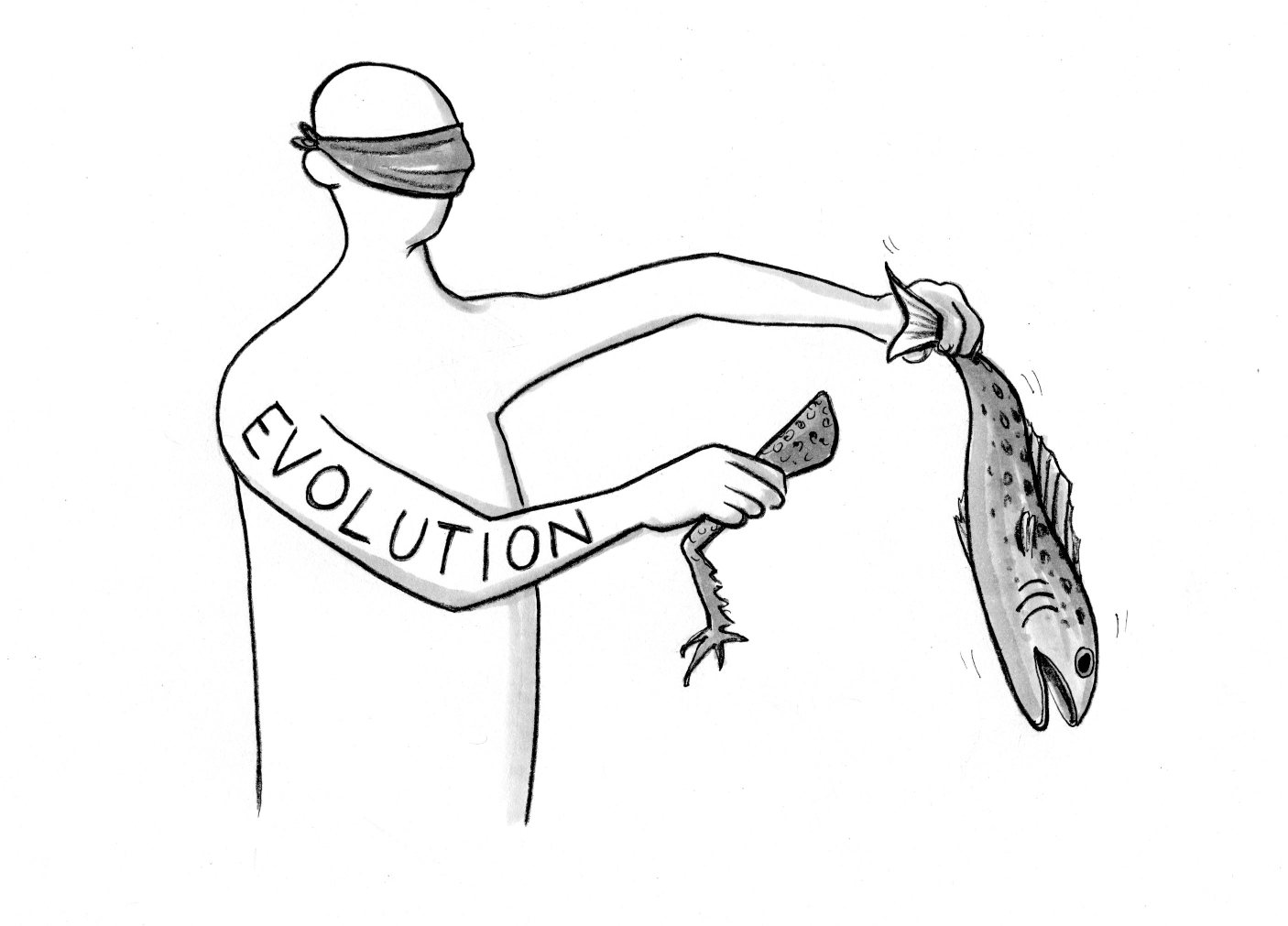

This is natural selection taking place among cells within a multicellular organism. Natural selection has no foresight. It is simply a physical process of replacement arising from differential survival and reproduction, regardless of the long-term consequences. The only way longer-term consequences become salient is through natural selection at the whole-organism level. A billion years of organism-level evolution (since multicellularity emerged) has resulted in effective cancer-suppression mechanisms, but they’re not perfect (see Maley, Aktipis, or Pepper).

So far we’ve seen natural selection among,

(a) Cells within a multicellular organism,

(b) Organisms within a single group,

(c) Groups in a multi-group population.

Human groups are a kind of organism. That concept has a long history in philosophical, religious, and political thought (e.g., the “body politic”), and it now rests on stronger scientific foundations. Between-group selection has endowed human social groups with impressive abilities to suppress disruptive within-group traits (just as multicellular organisms police and suppress internally disruptive cancer cells).

JB: So a pattern emerges: Evolutionary competition at one level limits survivable “selfishness” at lower levels (e.g., cancer’s mutinous mutations).

Plus, I’d suggest that a separate “natural filtering” operates … whereby certain kinds of “selfish” gains by rogue parts can be deadly, irrespective of whatever other factors from natural selection and evolution apply. If you hope to enjoy long-term viability, life’s logic requires that you not harm whatever supplies your needs (see needism).

For the next post in this diablog series, click here (How Evolution And Logic Relate: Natural Filtering vs Foresight).

For the previous post click here (Is Evolution Teeming with Unseen Teamwork?).

Illustration by Julia Suits, The New Yorker Cartoonist & author of The Extraordinary Catalog of Peculiar Inventions.