Politics & Current Affairs

All Stories

From corrupt czars to bloodthirsty Bolsheviks, Russia has had no shortage of bad leaders. But just how evil were they really?

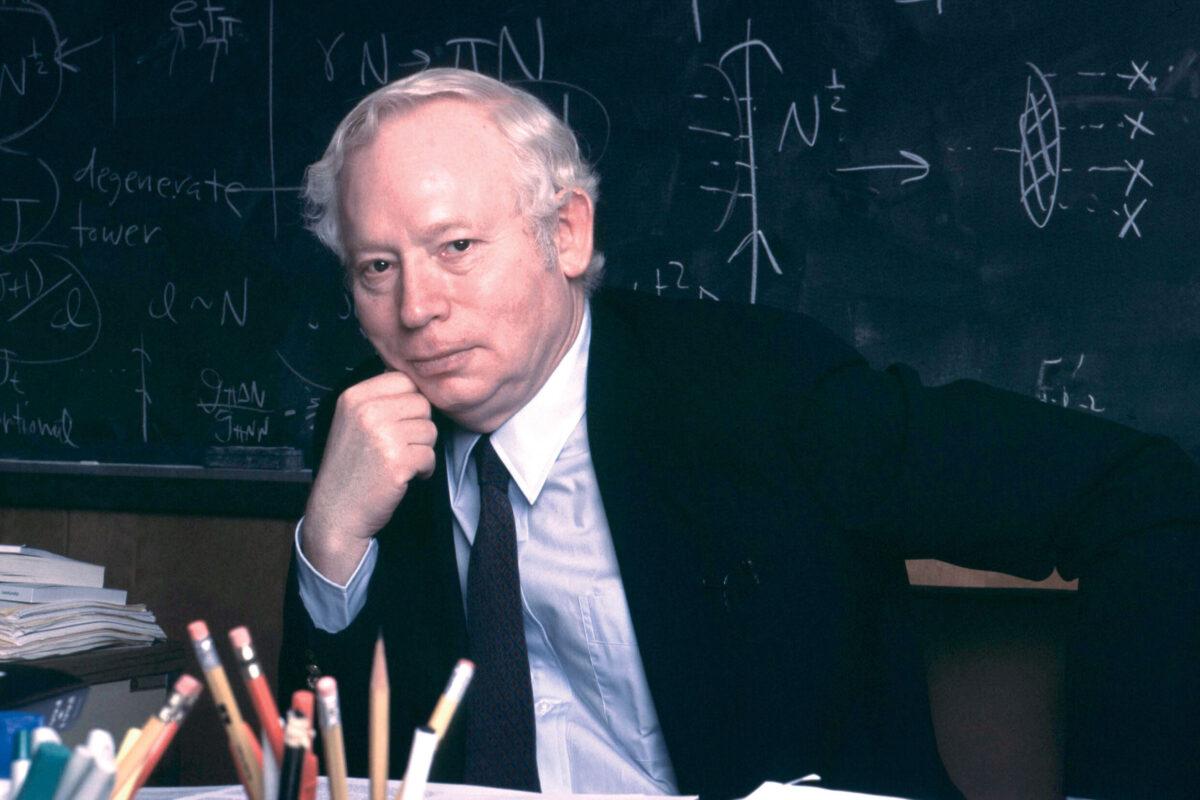

As important as his Nobel Prize-winning technical accomplishments was his ability to communicate to the public.

A retraction regarding a May 6, 2019 article entitled “Are these 100 people killing the planet?”

New findings show that Russian explosion was from a nuclear reactor.

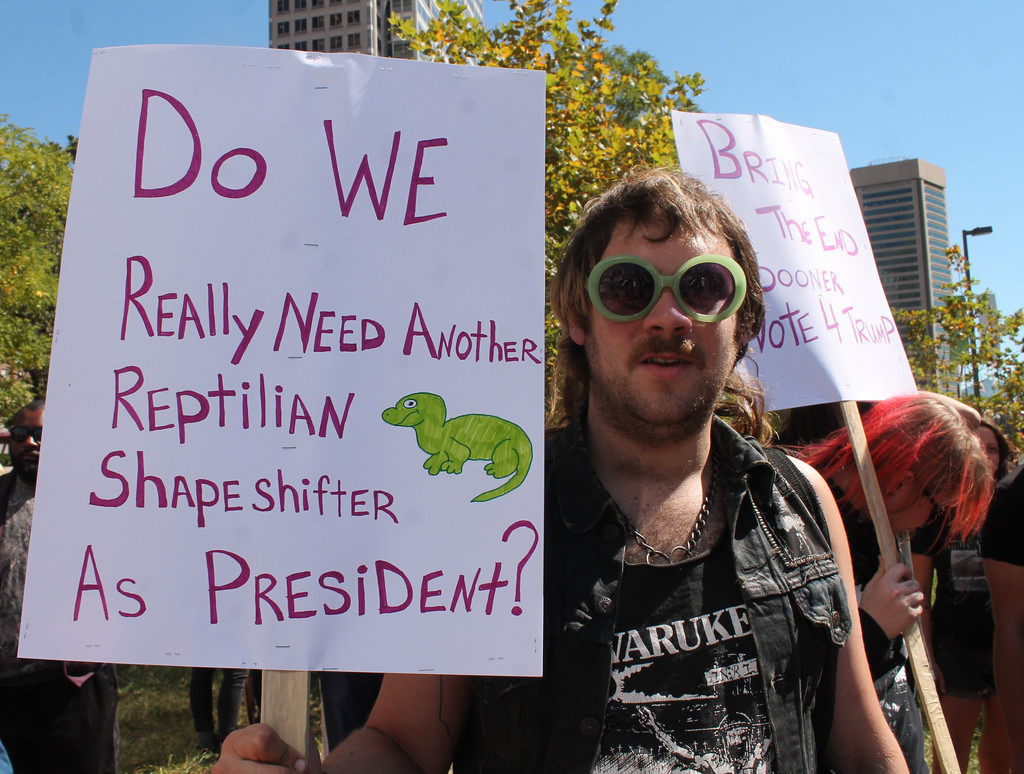

Conspiracies do happen. So, how do you know which theories might be worth investigating?

It’s the first time a Category 4 hit this region. Ever.

Black scientists lack role models who look like them.

On Sunday, a woman accused the Supreme Court nominee of sexual assault in an interview with the Washington Post.

Infographics show the classes and anxieties in the supposedly classless U.S. economy.

The maker of OxyContin, one of the world’s most widely abused opioids, has patented a drug that aims to help addicts wean off opioids.

A seismic shake-up at a venerable literary gatekeeper. Shallow and not-so-shallow consumerism. The Paris Review’s new editor on old ghosts, new voices, and what’s worth keeping.

The New York Times published an opinion column written by an anonymous “senior official in the Trump administration,” a rare move that’s sparked theories as to who the author might be.

Bernie Sanders introduces an act to Congress named for the uber-wealthy head of Amazon aiming to make wealthy companies pay for any employees receiving public assistance.

On Sept. 2, a fire spread through Rio de Janeiro’s National Museum, devouring the historic building and most of its 20 million culturally and scientifically important items. We look at nine priceless artifacts and collections likely lost in the blaze.

Writer and director Judd Apatow, one of several high-profile artists that threatened to drop out of the festival, said he wouldn’t participate in an event that “normalizes hate.”

A group of 200 artists, actors, musicians and scientists have signed an open letter calling for the world’s politicians to act “firmly and immediately” on climate change in order to avoid a “global cataclysm”.

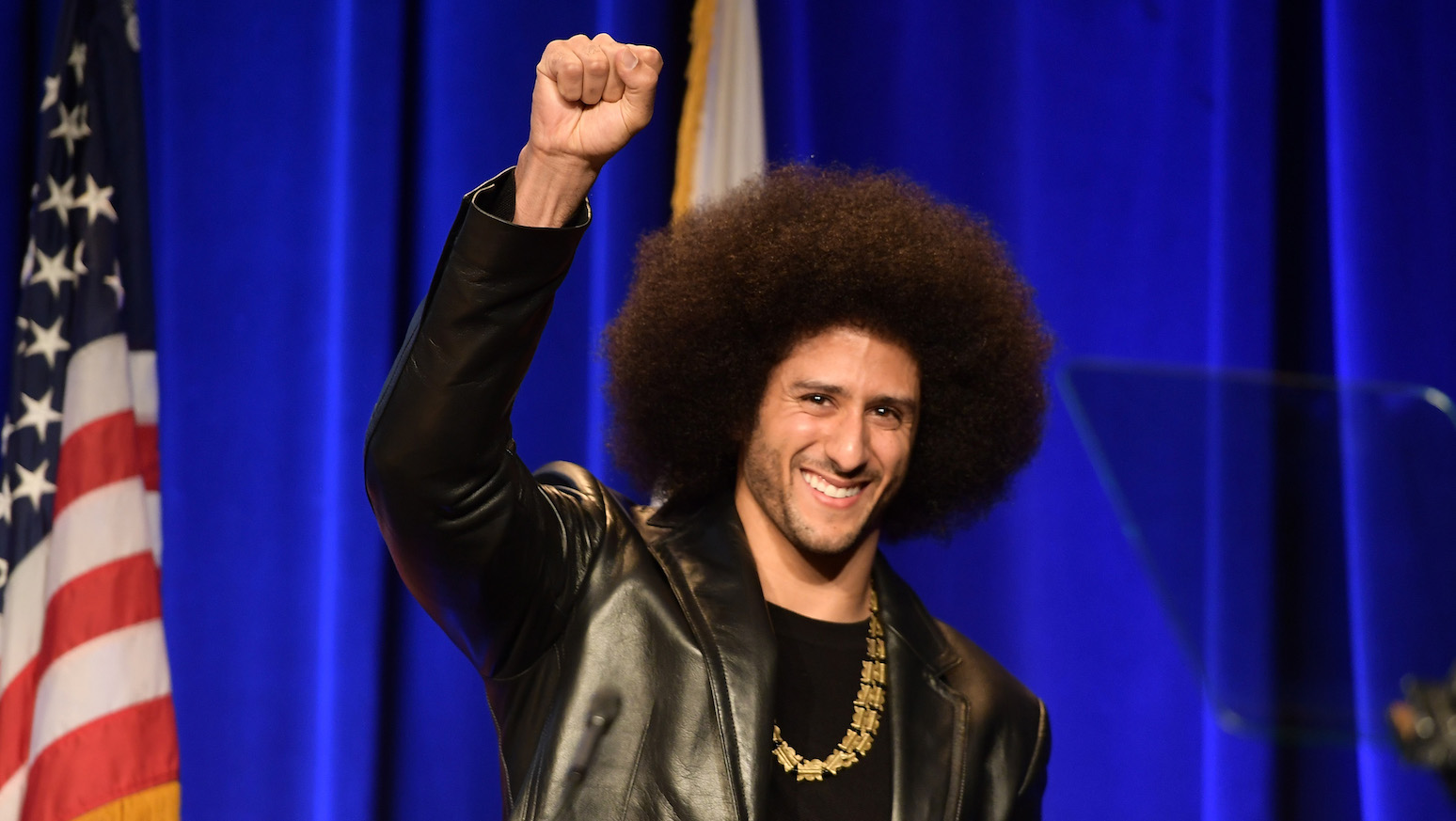

“Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything. #JustDoIt”

To put it mildly, North Korea has had a complicated relationship with the world. In chronological order, here are five of North Korea’s most incredible plots.

Although the scope of the strike isn’t clear yet, the strike organizers claimed that they anticipated inmate demonstrations in as many as 17 states.

It now moves to a full hearing in front of the arbitrator.

Senator John Sidney McCain III, who died Saturday, Aug. 25, 2018 at the age of 81, is lying in state in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol.

50 years ago the city of Chicago erupted in a legendary police riot.

Facebook allowed advertisements promoting gay conversion therapy to be targeted to users who had ‘liked’ pages related to LGBTQ issues, according to a recent investigation by The Telegraph.

A recently solved murder case from the Netherlands illuminates some of the promises and ethical questions raised by the police practice of using genealogy databases to identify criminal suspects.

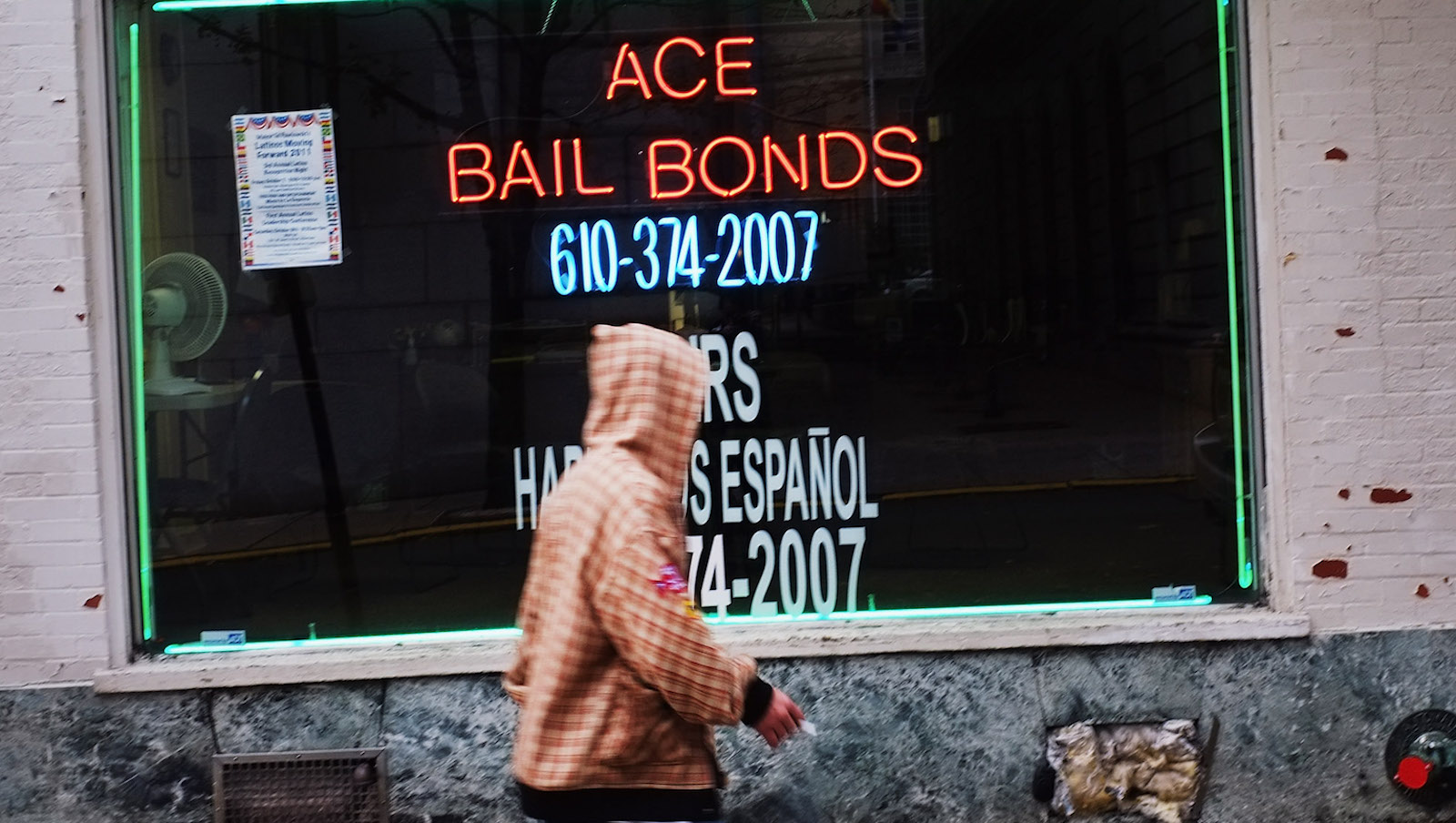

The state joins Washington, D.C. in eliminating a predatory system that preys upon low-income people and favors the wealthy.

The era of cheap energy is coming to an end and societies will need to reshape energy consumption and infrastructure or face consequences, warns a new scientific background paper issued to the United Nations.

On Tuesday, President Donald Trump claimed that Google is deliberately manipulating its algorithms to shut out conservative media outlets from news search results.

We hear the word ‘socialism’ a lot. What does it mean, exactly?

With Fort Lauderdale serving as an example, Avvo crunches the numbers to find the days of the month and week, and the times, you’re most likely to get a traffic ticket.

An interesting take on “fixing” the rampant corporate supremacy of the last 40 years.