How Egypt became one of the world’s richest nations during the 18th dynasty

- In Pharaohs of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of Tutankhamun’s Dynasty, historian Guy de la Bédoyère explores Egyptian history during the 18th dynasty, from 1550 BC to 1295 BC.

- Egypt was one of several significant Bronze Age states in the region.

- The history of the 18th Dynasty serves as an allegory of unrestrained ambition and greed for all times.

The gates of monarchs

Are arch’d so high that giants may jet through

And keep their impious turbans on without Good morrow to the sun.

— William Shakespeare

The events and history described in this book took place for the most part in ancient Egypt and beyond its borders to the north in the Near East or Western Asia and to the south in Nubia (Sudan). The timescale runs from the middle of the sixteenth century bc to the early thirteenth century bc, straddling the middle of ancient Egypt’s dynastic historical era of almost three thousand years. Literacy made Egypt one of the first nations with the ability to record its history permanently. The Egyptians were fully aware of this. A wisdom text from not long after the period covered by this book said, ‘Man decays, his corpse is dust. All his family have perished. But a book makes him remembered through the mouth of its reciter.’

The deeds and conceits of the kings and queens, and the elite, who presided over this remarkable nation were recounted and celebrated across Egypt’s monuments and on papyri. As history this astonishing archive leaves much to be desired and needs to be understood in the context of a completely different perception of the past. That record is nonetheless without parallel for the period and provides us with our first opportunity to witness in detail an early civilization at the height of its power.

Egypt’s famously unique geography has always made it a two-dimensional country. The vast bulk of human settlement in pharaonic times was stretched out along the Nile Valley and across the Delta. The oases of the Western Desert accounted for most of what habitable land remained. For the most part the Egyptians were engaged in sophisticated farming on the fertile land of crown, temple, and private estates saturated annually by the Nile’s inundation. Quarrying and mining took place in scattered locations in the Eastern Desert across which trade routes led to the Red Sea. In the broader context of human activity in the area even the grand antiquity of ancient Egypt accounts for only a tiny proportion. Tool-using peoples were present in the region as much as 400,000 years ago, and it is certain that human beings had been there for at least as long again before that after the first made their way north out of east Africa.

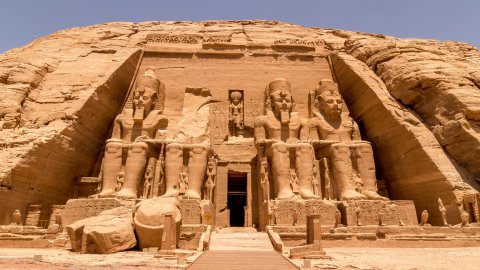

Within Egypt two of the most important places were the administrative capital Memphis in northern Egypt (close to modern Cairo), and to the south the religious capital at Thebes, on part of which the modern city of Luxor stands. Memphis and Thebes were the cities’ much later Greek names. In ancient Egyptian times they were referred to in various ways, explained later. During the 18th Dynasty, the first of the so-called New Kingdom, the kings spent much of their time at Memphis. The city’s profile has suffered in modern times because thanks to the shifting of the Nile almost nothing visible survives there today, apart from the pyramids, tombs and other religious structures of the nearby necropolis at Saqqara. Thebes is a different matter. On the east bank of the Nile the vast ruins of the temple complexes of Karnak and Luxor are among the most impressive ancient buildings of all time and in any place. Across the Nile on the west bank are the remains of the mortuary temples and royal and private graves. Much of what is visible today is of 19th Dynasty and later dates, but a significant proportion belongs to the 18th Dynasty.

The 18th Dynasty and the rest of the New Kingdom owed a great deal to the four centuries of the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 bc), despite an intervening era of instability known today as the Second Intermediate Period. During the Middle Kingdom, Egyptian society and culture developed ideas about kingship, bureaucracy and government, monumental architecture, an awareness of the outside world in the form of trade and technical innovations, and a more sophisticated identity and sense of self. The Teaching of Ptahhotep, for example, is a 12th Dynasty philosophical work concerned with how old age brings weakness and decay but also how wisdom only comes with age. It was one of many old writings known and studied in the New Kingdom.

Under the 18th Dynasty kings Egypt’s territorial ambitions were directed mainly to the north into Syria and Nubia to the south. Both places became major sources of wealth and resources, including manpower seized in war or levied as tribute. Egypt was one of several significant Bronze Age states in the region. Others included the Hittites from Hatti in what is now Turkey, Mitanni in Syria, Minoan Crete, and Mycenaean Greece. These nations were all ruled by versions of despotic monarchies. There was no sense of personal autonomy or self-determination, and no means of expressing or coordinating dissent. Political representation for the population lay centuries in the future, and then only in other emergent nations.

By the middle of the second millennium bc all these places exhibited growing signs of sophistication and had advanced skills in literacy and technology. The copper alloy known usually now as bronze was the basis of weaponry and tools. Iron was scarcely known in Egypt and elsewhere other than from meteorites. This explains why an Egyptian word which seems to have been used to refer to iron, biw, was phonetically virtually identical to the word for heaven. Iron did not become more widely available in Egypt until c. 500 bc and did not become an everyday metal until the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

The Egyptians had mastered their use of the Nile as a highway and could sail further afield in the Red Sea. The cul-de-sac of the eastern Mediterranean provided an extensive three-sided coastline which guided an endless procession of merchant vessels whose crews risked being wrecked on the rocky coasts that separated the ports. Their voyages through what the Egyptians knew as the ‘Great Green’, personified as a fertility deity, meant a continuous process of disseminating news, ideas, innovations and skills throughout the region.

For the most part the fate of each nation relied on the personal qualities and prestige of individual rulers. We are most familiar with Egypt. No official records of contemporary rulers of Mycenaean Greece or Minoan Crete survive, or their deeds. Only the folk memories of the Trojan War in Homer’s poetry and other myths tell us anything ‘historical’ about that era, though the results of archaeology are compatible with the Homeric image of chieftain-based city states either in alliance or at war with each other. The picture is a little fuller for the Western Asiatic states, with written evidence for some regimes, such as the Hittites, and their activities.

The evolving states had bureaucrats who compiled and managed archives, which in Egypt included laws recorded on the ‘40 skins’ (leather rolls). Egypt had been one of those first nations to lead the field over a thousand years before but was no longer exceptional.

Collectively these states were laying the foundations for the ways modern governments operate, communicate, manage resources and control their populations. Apart from Egypt, the sequence of rulers, events and history are often lost, leaving us with merely the relics of their citadels and graves, serving at best as only glimpses into their society. The remains of imported goods found in Egypt, the adoption of innovations like chariots, Egyptian exports and surviving diplomatic correspondence prove that Egypt was a dominant and advanced player in the Bronze Age world.

The 18th Dynasty lasted about 255 years from approximately 1550 bc to 1295 bc. This was roughly midway between the age of the pyramids and the end of Egypt as an independent country in 30 bc when it was absorbed into the Roman Empire. The 18th Dynasty was the latest manifestation of native royal power in Egypt which already stretched back well over fifteen centuries and is known to us as the first phase of the New Kingdom.

The history of the 18th Dynasty serves as an allegory of unrestrained ambition and greed for all times. A combination of factors brought into being a line of kings who presided over what became temporarily the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the region. Regardless of their individual abilities or lack of, they gradually discovered the extent to which they could indulge themselves by exploiting a population contained within a despotic system designed to ensure continuity and control. This propelled Egypt towards domination of the Near East, a position it had reached by the mid-fifteenth century bc. With that went so many other characteristics of an imperialist state: violence, the systematic extraction of resources and manufactured goods from conquered or vassal states, slavery, and a self-glorifying ideology based on the idea of a divinely backed monarchy. However, it also brought stability.

During this time Egyptian culture reached full maturity, benefiting from the evolution of skills and crafts to an exceptionally high standard. Egyptian society was capable of fielding major armies, working gold and silver into fabulous works of art, fashioning vast stone obelisks and monumental statues, and building gigantic temples. Literacy was well established in a minority of the population made up mainly of the elite classes which included the priesthood and professional scribes, and specialized artisans. Literacy was integral to the development of a sophisticated bureaucracy that governed the country and managed all these projects.

Much of this effort was expended on conspicuous waste, apart from creating an illusion of permanence. State vanity building projects were designed to glorify and perpetuate the regime as part of that mirage. The justification that drove this was immersed in a powerful and intoxicating religious ideology of the king as a living god. His living career and his journey to an ecstatic afterlife required an unmatched level of devotion and commitment. The king ruled as the sun god falcon Horus. At his death he became Osiris, Horus’ father who had been killed by his brother Seth and was brought back to life by his wife Isis, mother of Horus, and was succeeded by his son, the new Horus. The cycle was perpetual.

This way of life held Egypt together, bonding Egyptian society together in a shared ideology of existence in this life and the next. The system created livelihoods for the wider population through the trickle-down distribution of food and other goods necessary for subsistence, gifts of livestock and land and sometimes more valuable items by the king and the elite. For most of the time the celebrated fertility of the Nile Valley, thanks to the annual flood, guaranteed an unusually reliable source of food. Similarly, the power of the Egyptian state in the 18th Dynasty protected the people from the threat of foreign invasions, which became a serious issue in later times.

The system was founded on a narcotic sense of timeless stability, oppressive conservatism and total dependence on the state. The great monuments and the all-encompassing framework of religion existed primarily to serve the self-interest of the king and the elite by reinforcing control and acquiescence, even if the consequence was also to create security and dispel fear of chaos.

The idea of investing Egypt’s wealth in technological and social development for the greater good did not exist. When innovations emerged, usually from abroad, they were used only to benefit the interests of those in power, for example in the form of advanced military technology or luxury items. Wealth served to enrich the king and his family, and through gifts and endowments also the state cults and the elite. This was normal for a Bronze Age nation, but the scale on which it took place in Egypt’s 18th Dynasty was unprecedented.

Nothing was spent on public entertainment or associated facilities, apart from showcase religious processions, the promenading of the king in his chariot and the triumphal display of captives and their executed leaders. Music and hunting existed as leisure pursuits but were mainly the preserve of the elite who left a rich record of their lives compared to the vast bulk of the rest of the population. They are largely undetectable now apart from the monuments on which they laboured and occasional discoveries of their modest graves.

Trade today is a means by which the surplus production of a nation’s economy is exchanged through international markets. In antiquity the movement of goods was as likely to be determined by a nation’s ability to extort goods by force. Egyptian products of the 18th Dynasty could and did turn up elsewhere, for example in Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete, and Greece. In general, the movement of goods was more in Egypt’s favour, at her behest, and with coercion. The appearance of Cretan-style bull-leaping frescoes in an early 18th Dynasty palace in the Delta, and a temple to the cult of the Syrian goddess Astarte at Memphis, shows that the influences were not all one way.

Egypt under the 18th Dynasty operated an international state protection racket. Minor city states sometimes actively welcomed the insulation Egypt offered them against their stronger neighbours. The army played the most important role in turning Egypt into an imperialist predatory state. The legitimization of the 18th Dynasty was founded on the achievements of its first king, Ahmose I, who used the army to expel the Asiatic Hyksos kings from the Delta region and thereby reunified the nation. His successors followed his lead, seeking opportunities to invade Egypt’s neighbours to the north and south. Thereafter, apart from the occasional insurrection after the death of a pharaoh, the mere threat of an Egyptian invasion was normally enough to keep Egypt’s neighbours meekly handing over tribute. Eventually the rise of new nations, such as the Hittites, introduced fresh tensions towards the end of the 18th Dynasty.