oil

Electricity from solar energy is the cheapest it’s ever been, thanks largely to technological improvements and policies that reduce the risk of investing in renewable energy. That’s one of the […]

It’s one of the nation’s worst oil spills on record.

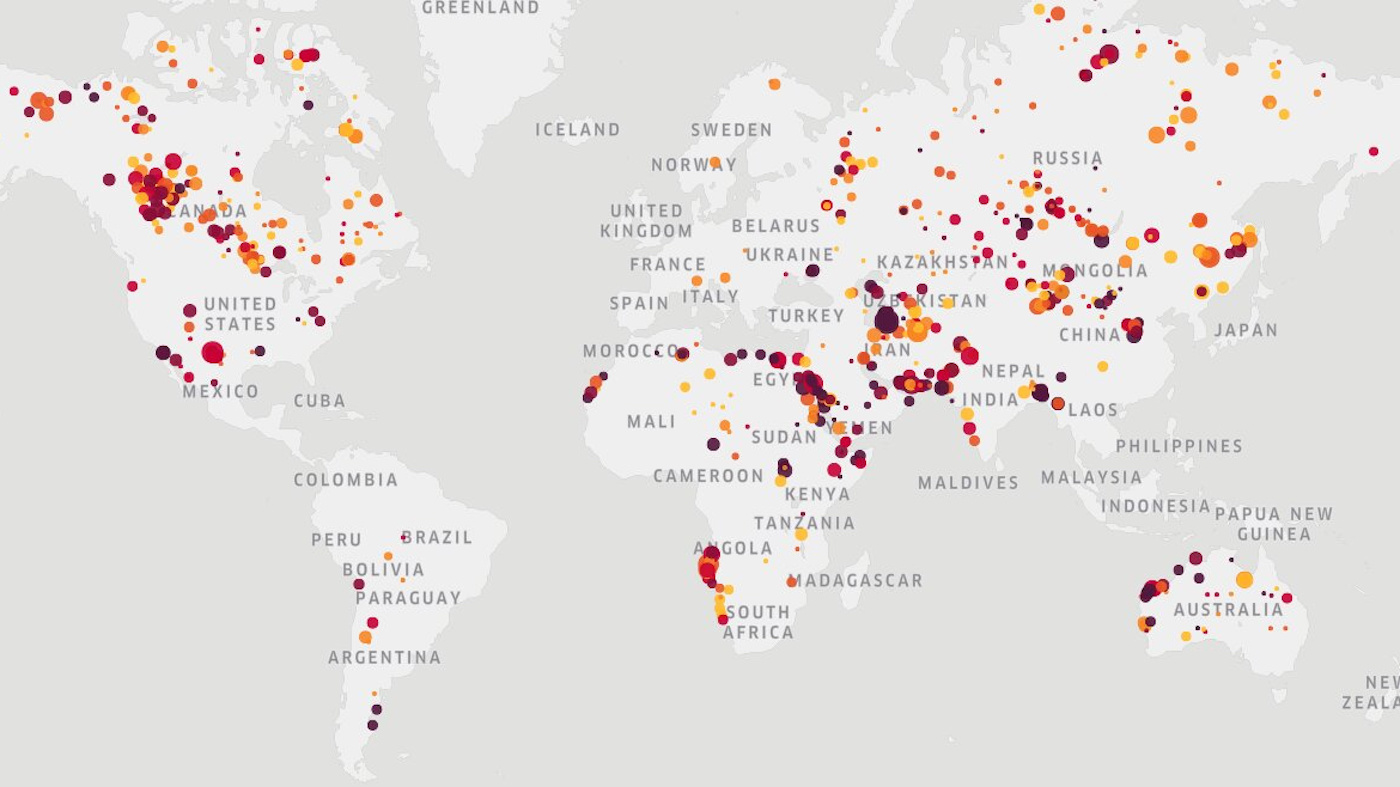

A European start-up uses satellite data to pinpoint individual sources of abnormal methane concentration.

Methane is 80 times more effective than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Researchers believe that war exacerbates climate change, threatening the environment and making future wars more likely.

A loophole signed into law during the Bush administration has been fiendishly tough to close.

The war machine needs fuel, perhaps so much as to make protecting oil redundant.

While there’s plenty to be worried about, it’s important to remember that we’re making progress, too.

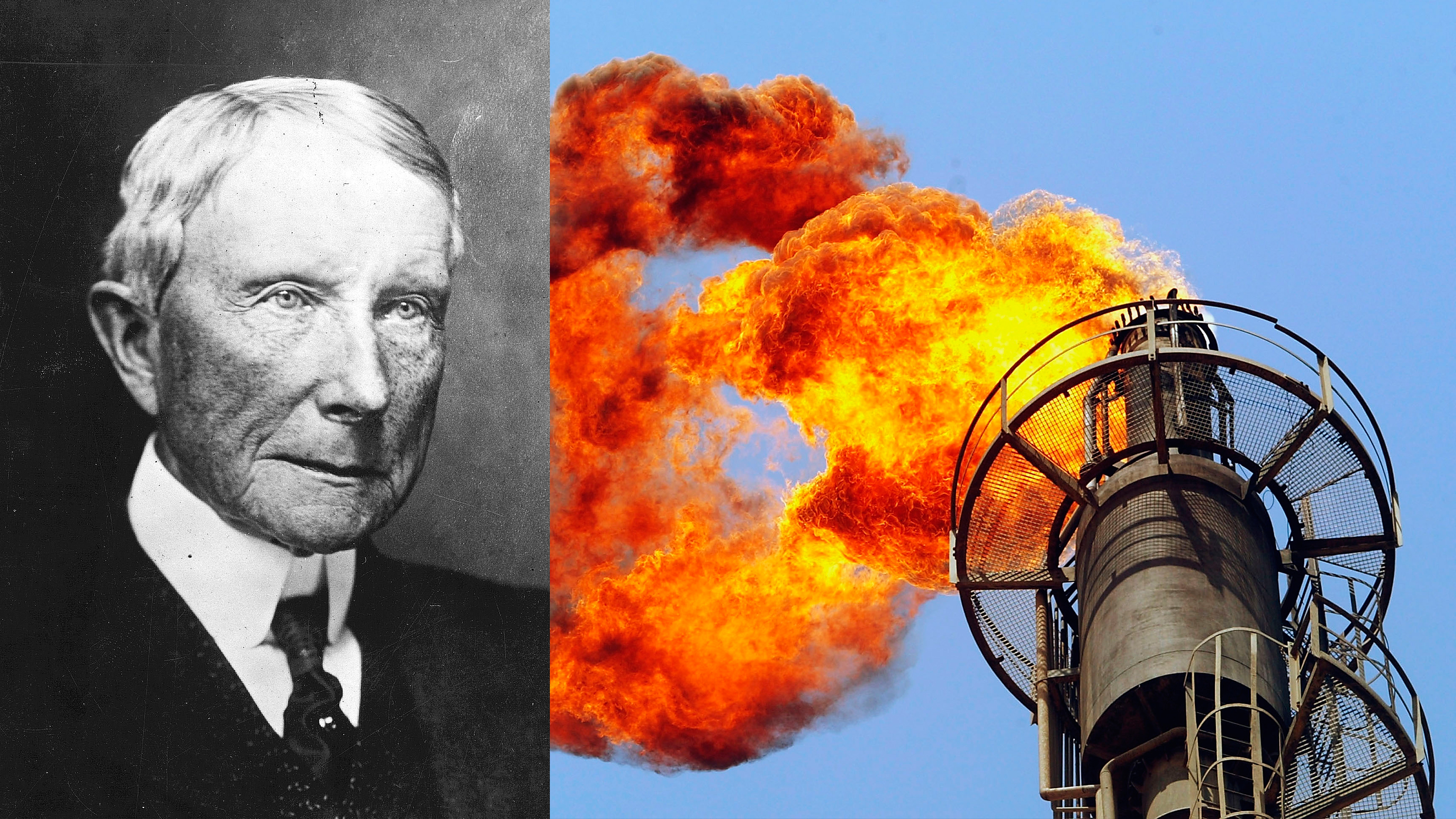

Climate change is a dire threat, perhaps it is time to put the people who created and denied the problem on trial?

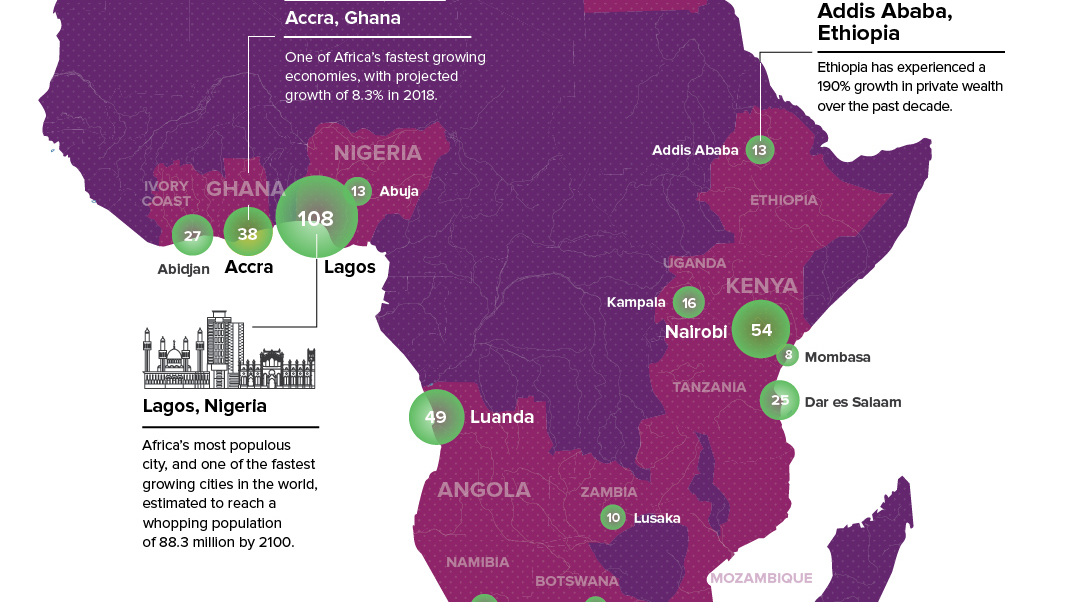

South Africa is no longer the only place on the continent that has urban wealth clusters

The feud between some of the Rockefellers and ExxonMobil has intensified.