Inequality

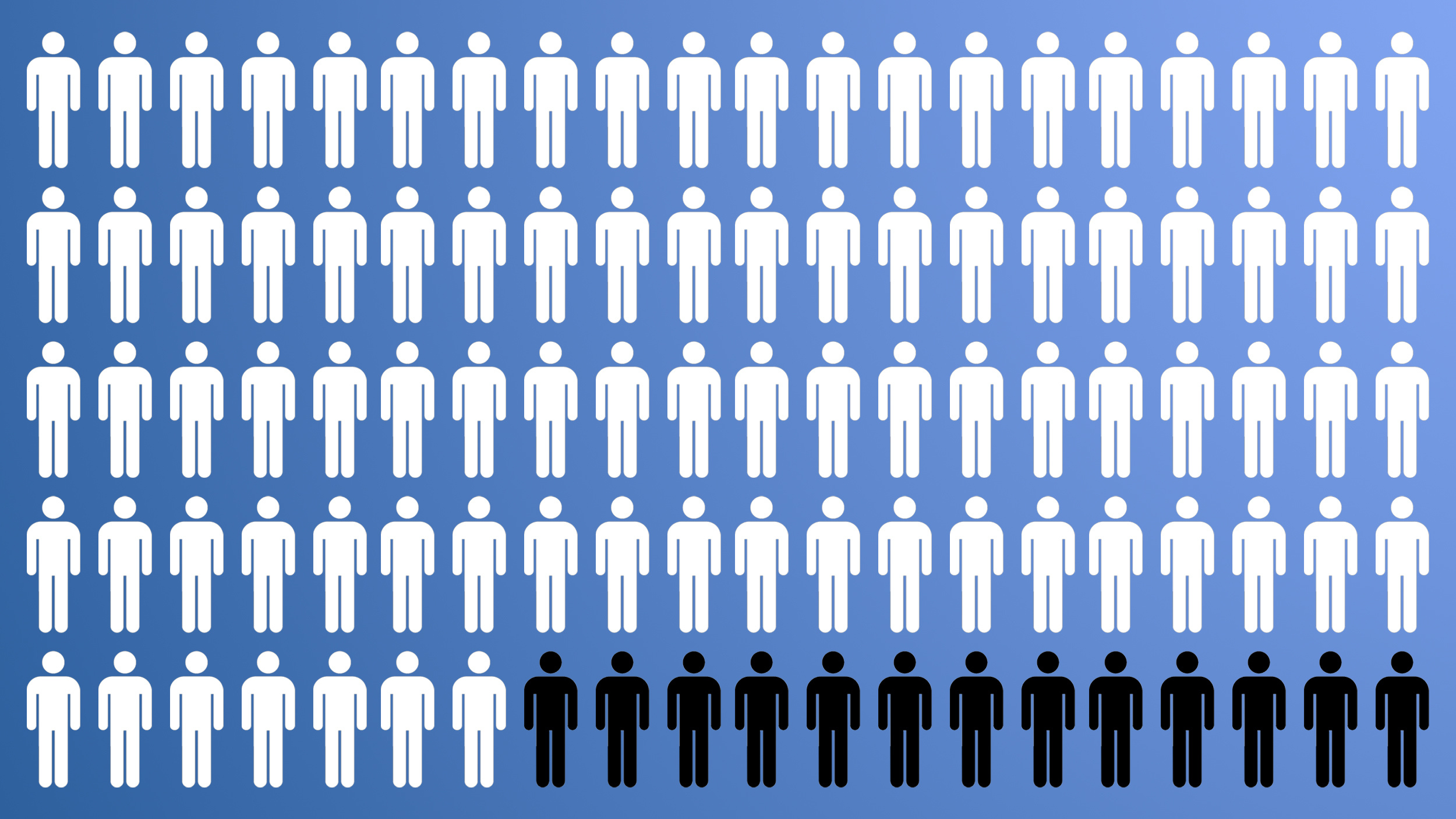

Male inequality — the enormous cultural shift happening right under our nose.

▸

15 min

—

with

A cartogram makes it easy to compare regional and national GDPs at a glance.

When does a healthy desire for wealth morph into greed? And how can we stop it?

As bad as this sounds, a new essay suggests that we live in a surprisingly egalitarian age.

The US prison system continues to fail, so why does it still exist?

▸

18 min

—

with

Hunter-gatherers probably had more spare time than you.

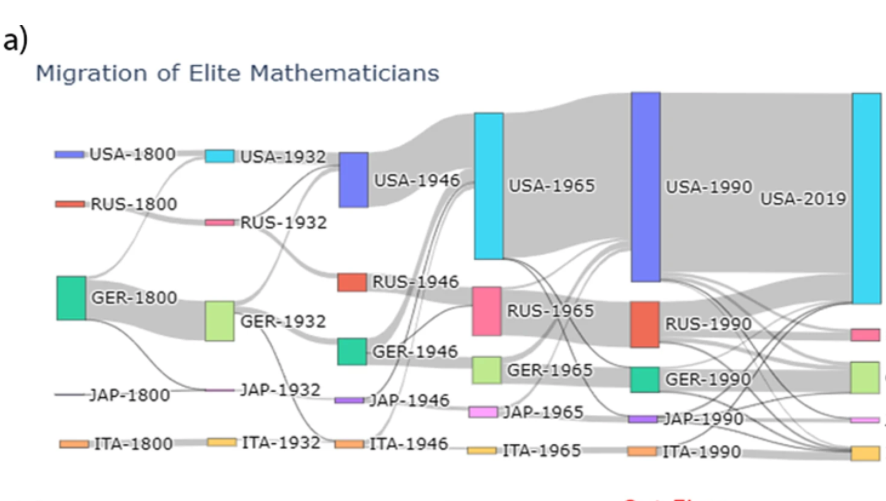

The Field Medal was created to elevate promising mathematicians from underrepresented demographics. But has it followed through on that goal?

The British economic anthropologist Jason Hickel proposes “degrowth” in the face of recession.

For democracy to prosper in the long term, we need more people to reach higher levels of education.

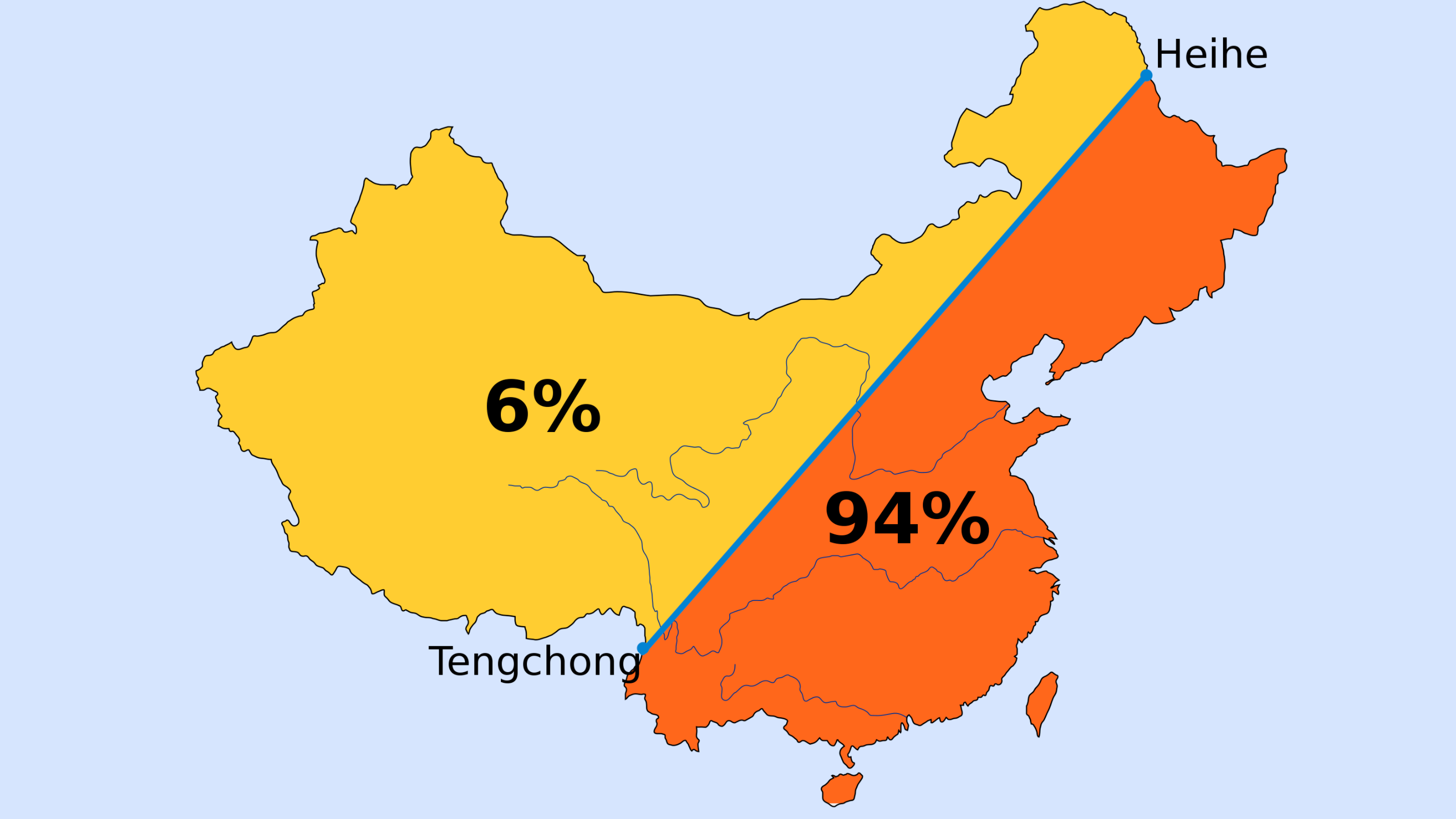

First drawn in 1935, Hu Line illustrates persistent demographic split – how Beijing deals with it will determine the country’s future.

Pandemics have historically given way to social revolution. What will the post-COVID revolution be?

Inequality in wealth, gender, and race grew to unprecedented levels across the world, according to OxFam report.

Want to tell someone’s future in the US? You don’t need a crystal ball, just their zip code.

Three decades after the demise of the GDR, its familiar contours keep coming back from the dead.

The next era in American history can look entirely different. It’s up to us to choose.

▸

5 min

—

with

The COVID-19 pandemic is making health disparities in the United States crystal clear. It is a clarion call for health care systems to double their efforts in vulnerable communities.

‘Critical Tourist Map of Oslo’ offers uniquely dark perspective on Norway’s capital.

In this 1915 map, Lady Liberty shines her light in the West on women in the East, still in electoral darkness

Monopolies wield an immense amount of economic and political power and influence. So what can we do to make the economy more equitable?

▸

5 min

—

with

Law professor Ganesh Sitaraman explains why America has never achieved true democracy—and how it can.

▸

6 min

—

with

Societies aren’t just engines of prosperity.

A new study shows how poor children are negatively impacted neurologically.

Less than 1% of all venture capital funding in the US is given to Black entrepreneurs. Now is the time for that to change.

From reassessing the way schools are funded to changing the curriculum, there are ways to fix the inequities in education.

▸

4 min

—

with

The American economy may be locked into an unhealthy cycle that only benefits a select few. Is it too late to fix it?

▸

19 min

—

with

Why do Black newborns have a relatively high mortality rate in the U.S. — and how does the race of the doctor factor in?

Sharing QAnon disinformation is harming the children devotees purport to help.

Researchers are using technology to make visual the complex concepts of racism, as well as its political and social consequences.

▸

5 min

—

with

Apparently the Catholic Church is a small business.