finance

Financial expert Paula Pant explains how you can afford anything, but not everything.

▸

7 min

—

with

Your emotional brain is being manipulated to shop more, but there are ways to resist.

▸

6 min

—

with

Science confirms what you already knew about being helpful to others.

▸

5 min

—

with

Playing video games could help you make better decisions about money.

▸

6 min

—

with

Why your brain wants you to follow the crowd.

▸

6 min

—

with

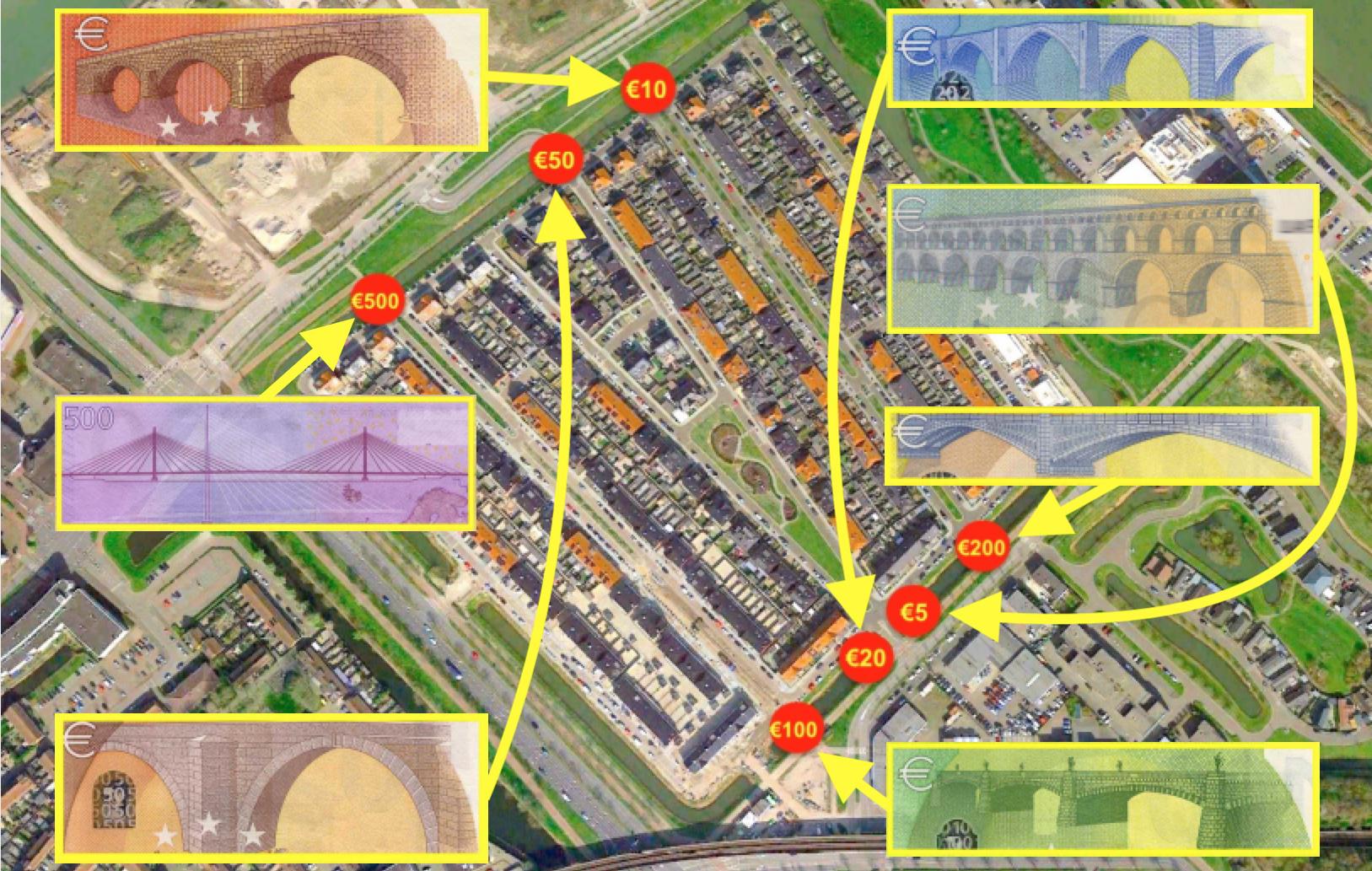

The European currency features buildings that didn’t exist, until Spijkenisse made them in concrete

Understand everything that goes behind payroll, debits, credits, and more with this 25-hour course collection.

A crash course in the history of money, the birth of Bitcoin, and blockchain technology.

▸

17 min

—

with

A new study casts doubt on previous research showing that emotional well-being plateaus at an income of $75,000 per year.

Research from MIT’s School Effectiveness & Inequality Initiative found making college more affordable cut dropout rates and boosted degree attainment.

A new survey found that 27 percent of millennials are saving more money due to the pandemic, but most can’t stay within their budgets.

Miso Robotics has already served up over 12,000 hamburgers.

Money can’t buy happiness, but try being hopeful and broke at the same time.

Finances can be a stressor, regardless of tax bracket. Here are tips for making better money decisions.

▸

15 min

—

with

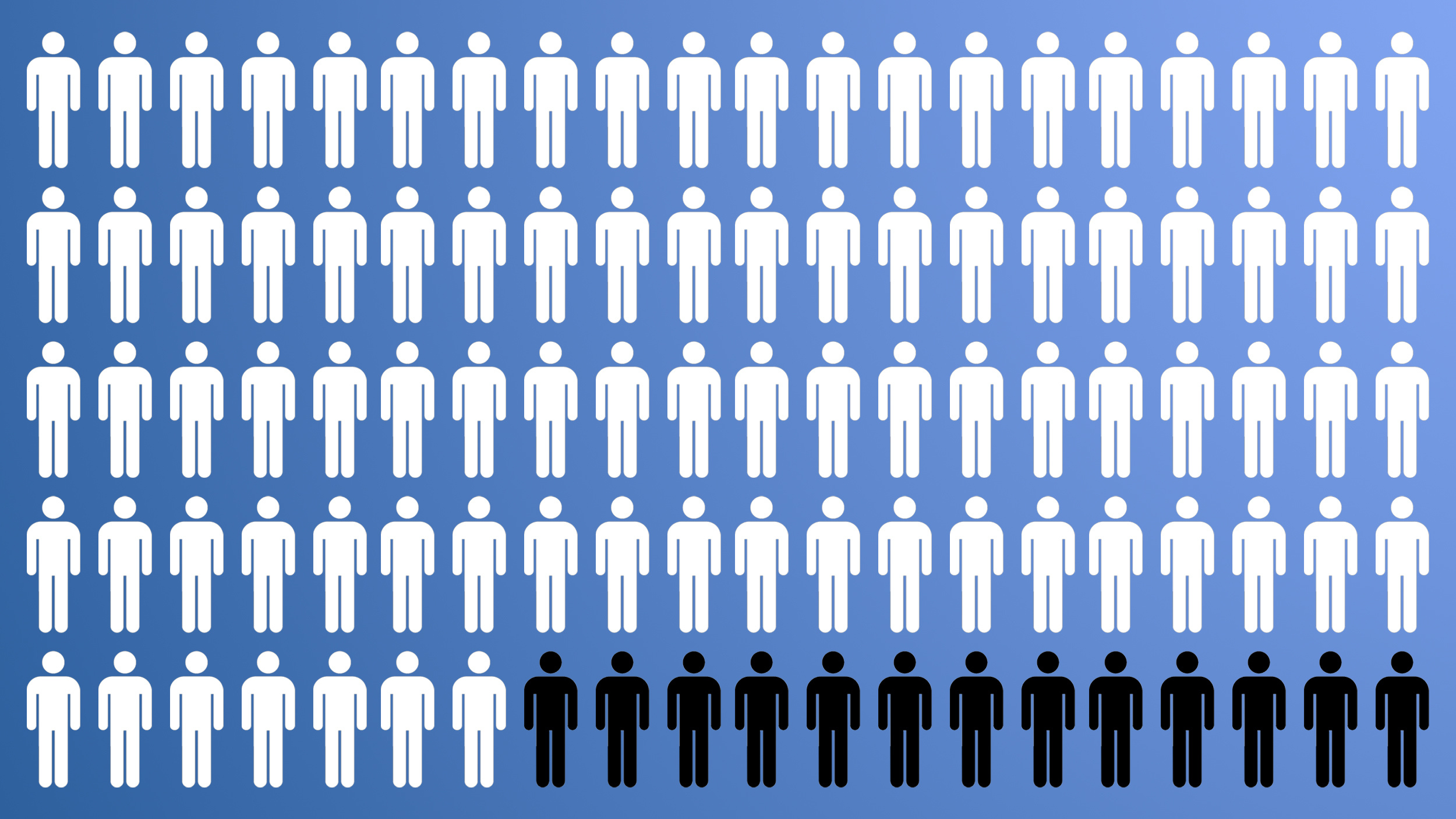

Less than 1% of all venture capital funding in the US is given to Black entrepreneurs. Now is the time for that to change.

Get 11 hours of proven techniques on candlestick, day trading, and investment.

Be your own accountant and handle your assets with this personal finance class bundle.

Join Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and best-selling author Charles Duhigg as he interviews Victoria Montgomery Brown, co-founder and CEO of Big Think.

▸

with

COVID-19 may strengthen the case for universal basic income, or an idea like it.

▸

24 min

—

with

Worthy returns 2-3x more money than local jewelers and pawn shops.

Sallie Krawcheck and Bob Kulhan will be talking money, jobs, and how the pandemic will disproportionally affect women’s finances.

▸

with

Transparency no doubt keeps organizations more accountable, but public companies need to reconnect with their true owners.

▸

4 min

—

with

I’m a small business owner in New York City. Until the CARES Act was passed, which offered loans to small businesses affected by the COVID-19 crisis, I’d forgotten my bank […]

How will the current challenges to the global economy pressure it to change?

▸

4 min

—

with

Unfortunately, it’s getting easier to predict what might happen to cryptocurrencies when the economy takes a nosedive.

Retail therapy has been proven to make us happier, but is there a catch?

It takes more than a good idea to land a shark as a business partner.

▸

5 min

—

with

What does your money personality say about how you save (and spend) money?