faith

Intrinsic religiosity has a protective effect against depression symptoms.

Spirituality can be an uncomfortable word for atheists. But does it deserve the antagonism that it gets?

Here’s what Einstein meant when he spoke of cosmic dice and the “secrets of the Ancient One”.

Placing science and religion at opposite ends of the belief spectrum is to ignore their unique purposes.

▸

14 min

—

with

A debate is raging inside and outside of churches.

A recent survey also found that political messaging from the pulpit increased the likelihood of believing presidents to be ordained by God.

Philosophy professor James Sterba revives a very old argument.

Spoiler: Microbiomes in space!

We live in contradiction. How we confront that fact matters.

We should care about constitutional rights for all, says lawyer and religious freedom scholar Asma T. Uddin. If they are denied for some, history demonstrates how they may be at risk for us all.

Does God exist? The answer rests outside the “normal” boundaries of science.

▸

3 min

—

with

Symbols are often used to help people get an idea of higher, often ineffable, truths.

▸

8 min

—

with

From religious wars to French poison conspiracies to the counterculture, we look at the origins of Satanism.

At one point, America needed to be called a Judeo-Christian nation. Now, with growing populations of Muslims, Evangelicals, Sikhs, Atheists, and other faiths, what should America call itself next?

▸

5 min

—

with

Comedian Pete Holmes details his struggle with faith, sex, and God.

▸

10 min

—

with

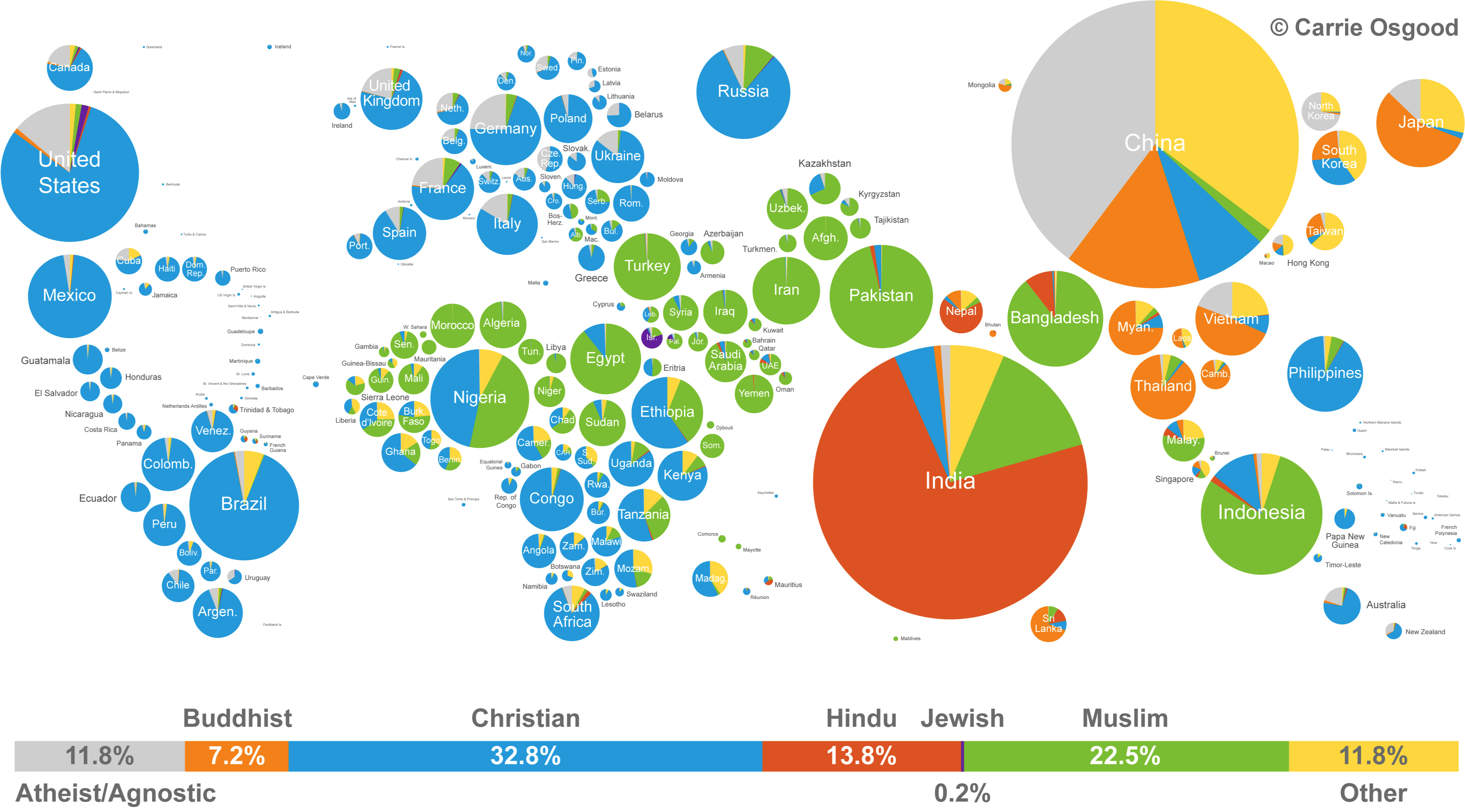

Both panoramic and detailed, this infographic manages to show both the size and distribution of world religions.

The gem lapis lazuli is the source of luminescent blue in manuscript illustrations.

She met mere mortals with and without the Vatican’s approval.

The countdown continues! This is the 7th most popular video of 2018.

▸

4 min

—

with

Eboo Patel explains how America’s political philosophy broke the democratic mold.

▸

4 min

—

with

Where is God? Michelle Thaller lays out a cosmic view of religion, science, and the human condition.

▸

5 min

—

with

Christmas has many pagan and secular traditions that early Christians incorporated into this new holiday.

Maybe we should stop worrying about what happens after we die, and make the best of what we have on earth right now.

▸

6 min

—

with

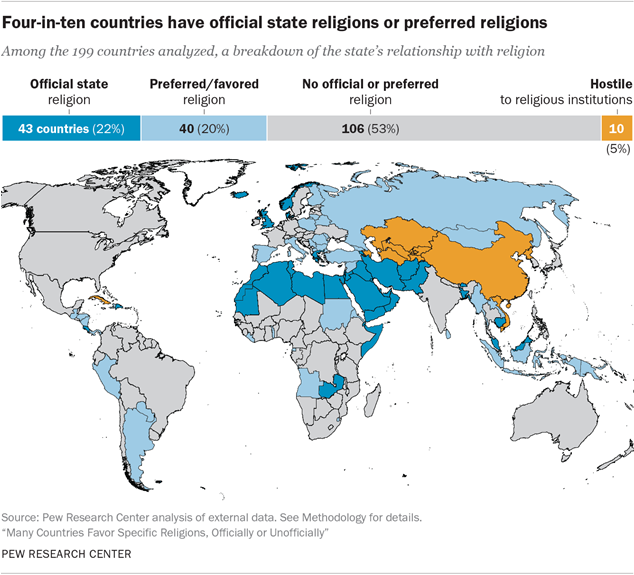

Pew Research also reports that 10 nations are outright hostile to religion.

Rabbi Darren Levine explains how the psychology of happiness intersects with religious practice.

▸

8 min

—

with

Where are the four “horsewomen” of new atheism? Well, here are two of them, secular scholars Rebecca Goldstein and Susan Jacoby.

You have to be a little envious of those who have faith—they have a motivational force behind them that is near impossible to beat. What if there was a secular equivalent, wonders philosophy professor Sam Newlands.

▸

4 min

—

with

What does Robert Sapolsky—an “utter, complete, atheist”—think about the persistence of magical thinking in our modern world?

▸

3 min

—

with