France Just Radically Changed its Organ Donation Policy

Think of a place where you go periodically where you are around about 20 people. It can be your job, a classroom, or when you’re amongst fellow commuters on your daily ride to work. Now, picture those people vanishing, one by one before your very eyes, never to return. There is nothing anyone can do. And it doesn’t happen once, but over and over, day after day. Sound like the plot of a horror movie? It’s reality. 22 people are lost each day in the US waiting for a healthy organ for transplant.

Over 119,000 names are on the national transplant waiting list as you read this. Every ten minutes, another name is added. These are fathers, mothers, siblings, partners, and someday if your luck runs out, maybe even you. 30,970 transplants occurred in the US in 2015, the highest number on record. The rest wait and hope to get lucky.

There are some urban legends out there, such as first responders not administering lifesaving procedures if the person is an organ donor, which it goes without saying is patently false. However, there is an extreme shortage of organs the world over. And out of 1,000 deaths, only three people leave suitable organs. To compound the issue further, there aren’t enough donors on the list. While 95% of Americans say they support organ donation, only 48% are donors themselves.

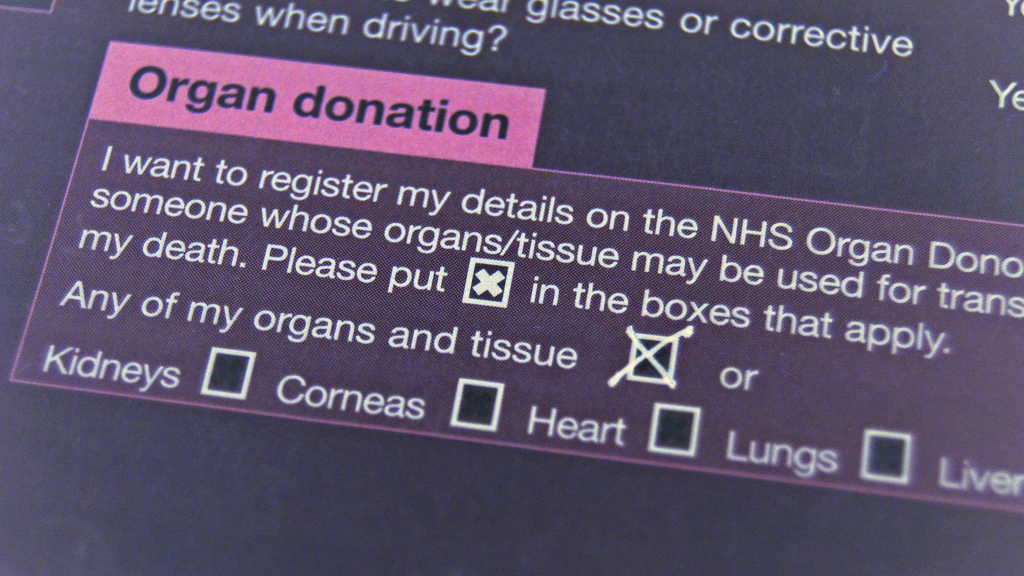

Western Europe has a similar problem. There, the UK has one of the lowest rates of consent. A record number of transplants occurred in that country last year. Even so, the UK is 80% short of its target, which is supposed to be met by 2020. Relative opposition is one of the biggest stumbling blocks. Relatives can veto the process even if the person is registered to be a donor. In the EU, 86,000 were on the organ transplant list in 2014. Today a good percentage, around 19,000, are French nationals. Because of this, French MPs have taken a radical step to narrow the gap.

Viable organs for transplant are scarce. France is attempting to remove some roadblocks.

Starting January 1, instead of actively selecting to be an organ donor, adults in France will automatically be enrolled. There is an option to abstain, but you have to officially opt out. Currently the national refusal register (Registre National des Refus) has 150,000 people in its database. One can sign up online, however. So it isn’t terribly inconvenient. The process is even outlined on the bureau’s Facebook page. Those who are opposed who do not register, can leave a signed letter or even tell their loved one orally, which must be put into writing and given to their doctor at the time of death.

One shocking element, the person’s organs are harvested, whether or not the family supports it. This is because previous to the new law, when someone’s wishes weren’t made clear before their death, and relatives were approached about the subject of donation, the family refused up to 40% of the time. Health minister Marisol Touraine proposed this change in policy. In the new wording of the law, family members will be “told” of their loved ones organ donation rather than “consulted.” According to Socialist MP Michèle Delaunay, family members grieving over the death of a loved one often refuse donation initially, and later on regret it.

The law wasn’t without opposition. Around 270 healthcare professionals, mostly doctors and nurses, signed a petition against the new rules. Besides questioning its ethical stance, petitioners say the law could put more static between relatives and hospital staff during a trying time. One surgeon said it would make some family members “maddened” and even “unmanageable.”

French organ donation organizations were happy, as one might expect. One such group, Greffe de Vie, said it could save 500 to 1,000 lives per year, by its estimates. Other nations in Europe have similar systems, such as Spain, Austria, and Wales. Though controversy can crop up, research has shown that such a policy can boost organ donation. Other countries are also considering changes to their policies. This isn’t the only attempt by the French government boost organ donation. A film about it aimed at 15 to 25 year-olds was released last November, promoted by the Agence de la Biomédecine.

To learn more, click here: